When woodcut artist Katsushika Hokusai made his famous print The Great Wave off Kanagawa in 1830 — part of the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji — he was 70 years old and had lived his entire life in a Japan closed off from the rest of the world. In the 19th century, however, “the rest of the world was becoming industrialized,” James Payne explains above in his Great Art Explained video, “and the Japanese were concerned about foreign invasions.” The Great Wave shows “an image of Japan fearful that the sea — which has protected its peaceful isolation for so long — would become its downfall.”

It’s also true, however, that The Great Wave would not have existed without a foreign invasion. Prussian blue, the first stable blue pigment, accidentally invented around 1705 in Berlin, arrived in the ports of Nagasaki on Dutch and Chinese ships in the 1820s. Prussian Blue would start a new artistic movement in Japan, aizuri‑e, woodcuts printed in bright, vivid blues.

“Hokusai was one of the first Japanese printmakers to boldly embrace the colour,” Hugh Davies writes at The Conversation, “a decision that would have major implications in the world of art.” When the country’s isolationist policies ended in the 1850s, “a showcase at the inaugural Japanese Pavilion elevated the artistic status of woodblock prints and a craze for their collection quickly followed.”

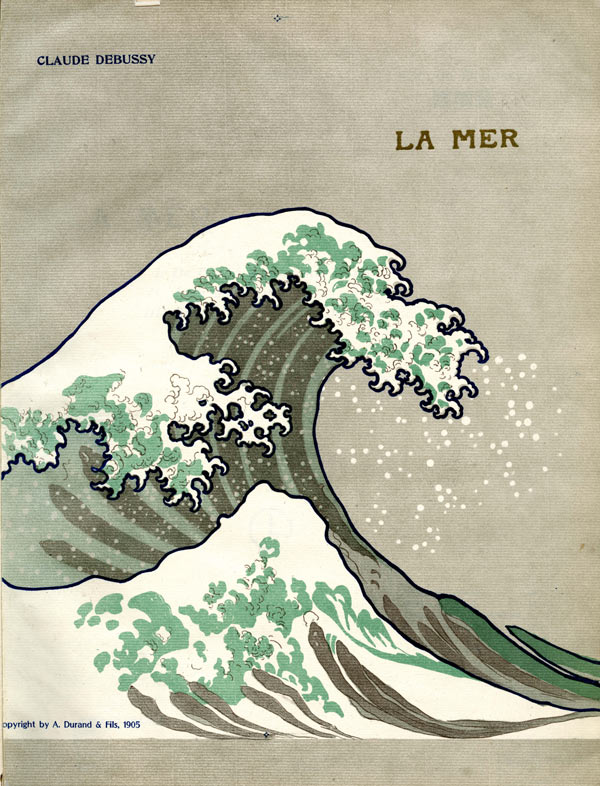

Chief among the works collected in the European and American fervor for Japanese prints were those from Hokusai, his contemporary Hiroshige, and other aizuri‑e artists. So famous was The Great Wave in the West by 1891 that French graphic artist Pierre Bonnard would satirize its stylish spray in an advertisement for champagne. A print of The Great Wave hung on Claude Debussy’s wall, and the first edition of his La Mer bore an adaptation of a detail from the print. As Michael Cirigliano writes for the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Cultural circles throughout Europe greatly admired Hokusai’s work…. Major artists of the Impressionist movement such as Monet owned copies of Hokusai prints, and leading art critic Philippe Burty, in his 1866 Chefs-d’oeuvre des Arts industriels, even stated that Hokusai’s work maintained the elegance of Watteau, the fantasy of Goya, and the movement of Delacroix. Going one step further in his lauded comparisons, Burty wrote that Hokusai’s dexterity in brush strokes was comparable only to that of Rubens.

These comparisons are not misplaced, John-Paul Stonard explains in The Guardian: “That the Great Wave became the best known print in the west was in large part due to Hokusai’s formative experience of European art.” Not only did he absorb Prussian blue into his repertoire, but “prints from early in his career show him attempting, rather awkwardly, to apply the lesson of mathematical perspective, learnt from European prints brought into Japan by Dutch Traders.” By the time of The Great Wave, he had perfected his own synthesis of Western and Japanese art, over two decades before European painters would attempt the same in the explosion of Japanophilia of the late 19th and early 20th century.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply