Editor’s Note: This month, MIT Open Learning’s Peter B. Kaufman has published The New Enlightenment and the Fight to Free Knowledge, a book that takes a historical look at the powerful forces that have purposely crippled our efforts to share knowledge widely and freely. His new work also maps out what we can do about it. In the coming days, Peter will be making his book available through Open Culture by publishing three short essays along with links to corresponding sections of his book. Today, you can read his second essay “On Wikipedia, the Encyclopédie, and the Verifiability of Information” (below), plus download the second chapter of his book here. Read his first essay, “The Monsterverse” here, and purchase the entire book online.

When the ideas that matter most to us – liberals, democrats, progressives, republicans, all in the original sense of the words – were first put forward in society in order to change society, they were advanced foremost in print. The new rules, new definitions, and new codicils of human and civil rights that undergird many of the freedoms we value today had as their heart text and its main delivery mechanism, the printing press.

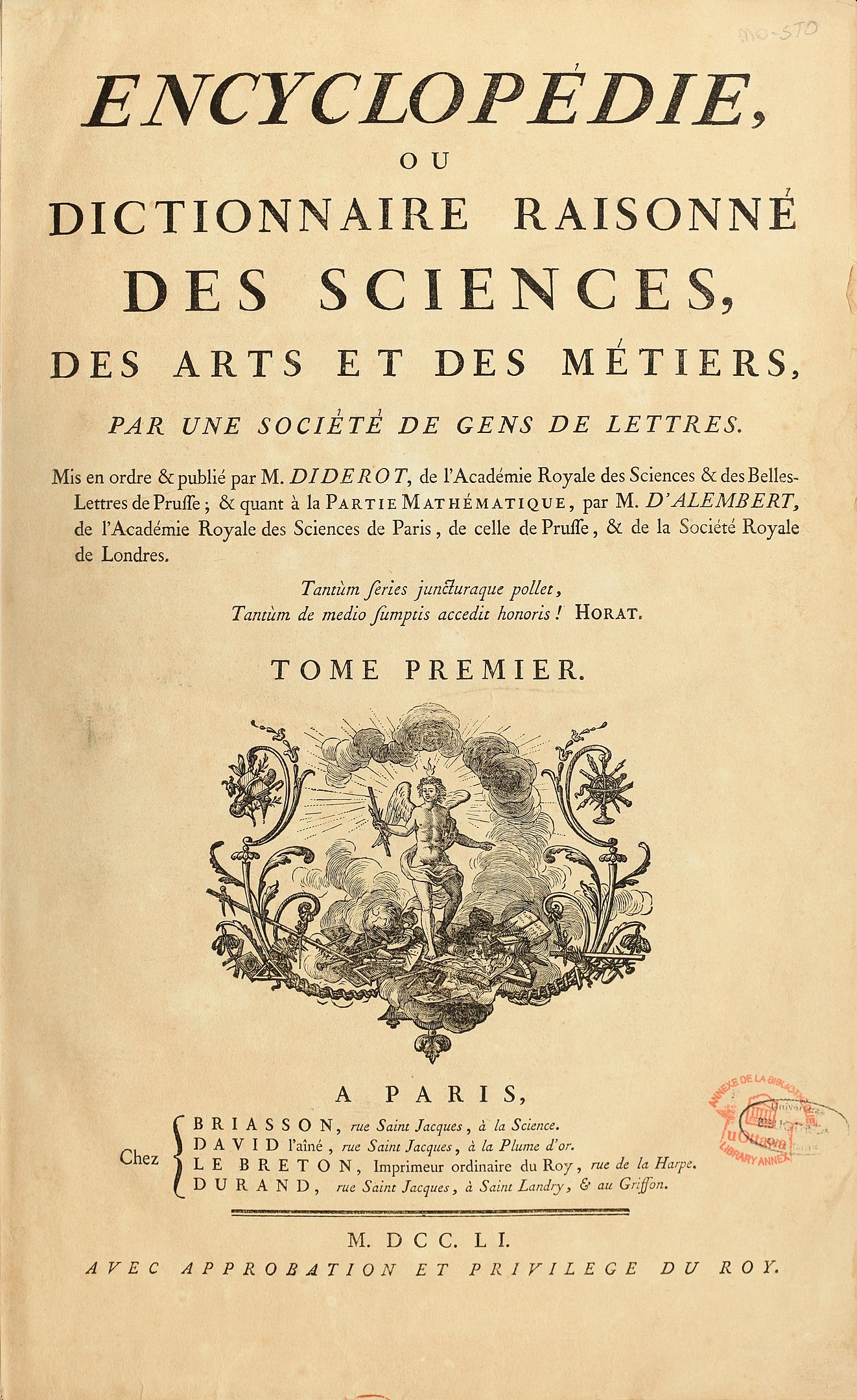

In that sense the first Enlightenment was based upon the foundation of the printed word. And of the 18th century’s contributions to knowledge and society – Newton’s physics, Montesquieu’s laws, Linnaeus’s taxonomies, Rousseau’s political philosophy, the Declaration of Independence, the Declaration of the Rights of Man – there was perhaps no greater printed offering than the 22-million-word Encyclopédie that the French Enlightenment philosophers starting writing, compiling, and offering to the public in 1750.

The Encyclopédie was monumental. Not just from a content-assembly perspective – an effort to gather all the world’s knowledge and to print and publish it – but also from a sociopolitical one, given the powerful forces suppressing knowledge that such an effort would provoke. The Encyclopédie found the state and the church banning at one time or another almost every one of its 72,000 articles, 18,000 pages, and 28 volumes and invoking a hundred ways to forbid its distribution.

The encyclopedia’s entire approach to collecting and presenting knowledge was radical. The articles presented truths – some heretical, some blasphemous – that astonished contemporary readers. And its innovative approach to the verification its own content, to proving what could be proved, which was really its nuclear core, rocked the Western world.

The Encyclopédie smote 18th-century orthodoxy with ink-and-paper sledgehammers. The article on “RAISON,” or “REASON,” for example, told every reader who for centuries had been steeped in church doctrine and the divine rights of royals that:

No proposition can be accepted as divine revelation if it contradicts what is known to us, either by immediate intuition, as in the case of self-evident propositions, or by obvious deductions of reason, as in demonstrations. It would be ridiculous to give preference to such revelations, because the evidence that causes us to adopt them cannot surpass the certainty of our intuitive or demonstrative knowledge…

Clerics and kings, needless to say, were not fans. Articles on religion, philosophy, and politics and society challenged the government and the church even as the censors watched. Direct swipes at the monarchy and the church appeared even where you might not expect – in articles on CONSCIENCE, LIBERTÉ DE; CROISADES; FANATISME; TOLÉRANCE; etc. The entry for FORTUNE spotlighted the gross inequalities of wealth already evident in 18th-century Europe. And a zinging condemnation of slavery in the article on the SLAVE TRADE made few friends among any who had a hand anywhere in the business.

Slave trade is the purchase of Negroes made by Europeans on the coasts of Africa, who then employ these unfortunate men as slaves in their colonies. This purchase of Negroes to reduce them into slavery […] violates all religion, morals, natural law, and human rights.

The Encyclopédistes announced from day one that this new work would be, as we would say today, fact-based. There would be an underlying and overarching commitment on the part of all contributors and the work as a whole to the verification of all of its source materials. Verification is potentially “a long and painful process,” Diderot wrote in his introduction to the whole enterprise – the famous “Preliminary Discourse” that these philosophers used to sell in the whole project:

We have tried as much as possible to avoid this inconvenience by citing directly, in the body of the articles, the authors on whose evidence we have relied and by quoting their own text when it is necessary.

We have everywhere compared opinions, weighed reasons, and proposed means of doubting or of escaping from doubt; at times we have even settled contested matters.… Facts are cited, experiments compared, and methods elaborated … in order to excite genius to open unknown routes, and to advance onward to new discoveries, using the place where great men have ended their careers as the first step.

What this meant in practice was revolutionary. There would be no accepted truths but for those that could be proven and cited. Fact-based versus faith- and belief-based: the start and spark of the Enlightenment. One of Diderot’s biographers explains that approximately 23,000 articles had at least one cross-reference to another article in one of the encyclopedia’s 28 volumes. “The total number of links – some articles had five or six – reached almost 62,000.” And all while retaining a sly sense of humor. The article on CANNIBALS ended with “the mischievous cross-reference,” as another historian would later describe it: “See Eucharist, Communion, Altar, etc.”

That commitment to reference citation continues in the Enlightenment’s most important successor project – Wikipedia, founded by Jimmy Wales and colleagues 20 years ago this year. It’s the foundation of what today’s Wikipedia terms verifiability, and in many key ways it’s the foundation for truth in knowledge and society today:

“Verifiability” … mean[s] that material added to Wikipedia must have been published previously by a reliable source. Editors may not add their own views to articles simply because they believe them to be correct, and may not remove sources’ views from articles simply because they disagree with them.

[V]erifiability is a necessary condition (a minimum requirement) for the inclusion of material, though it is not a sufficient condition (it may not be enough).

In 1999, free-software activist Richard M. Stallman called for this universal online encyclopedia covering all areas of knowledge, along with a complete library of instructional courses – and, equally important, a movement to develop it, “much as the Free Software Movement gave us the free operating system GNU/Linux.” That call (reproduced in full as the appendix in my book) is credited by Wikipedia as the origins of the work that is now the largest knowledge resource in history.

The free encyclopedia will provide an alternative to the restricted ones that media corporations will write.

Stallman published a list of what that the encyclopedia would need to do, what sort of freedoms it would need to give to the public, and how it could get started.

An encyclopedia located everywhere.

An encyclopedia open to anyone—but, most promisingly, to teachers and students.

An encyclopedia built of small steps.

An encyclopedia built on the long view: “If it takes twenty years to complete the free encyclopedia, that will be but an instant in the history of literature and civilization.”

An encyclopedia containing one or more articles for any topic you would expect to find in another encyclopedia – “for example, bird watchers might eventually contribute an article on each species of bird, along with pictures and recordings of its calls” – and “courses for all academic subjects.”

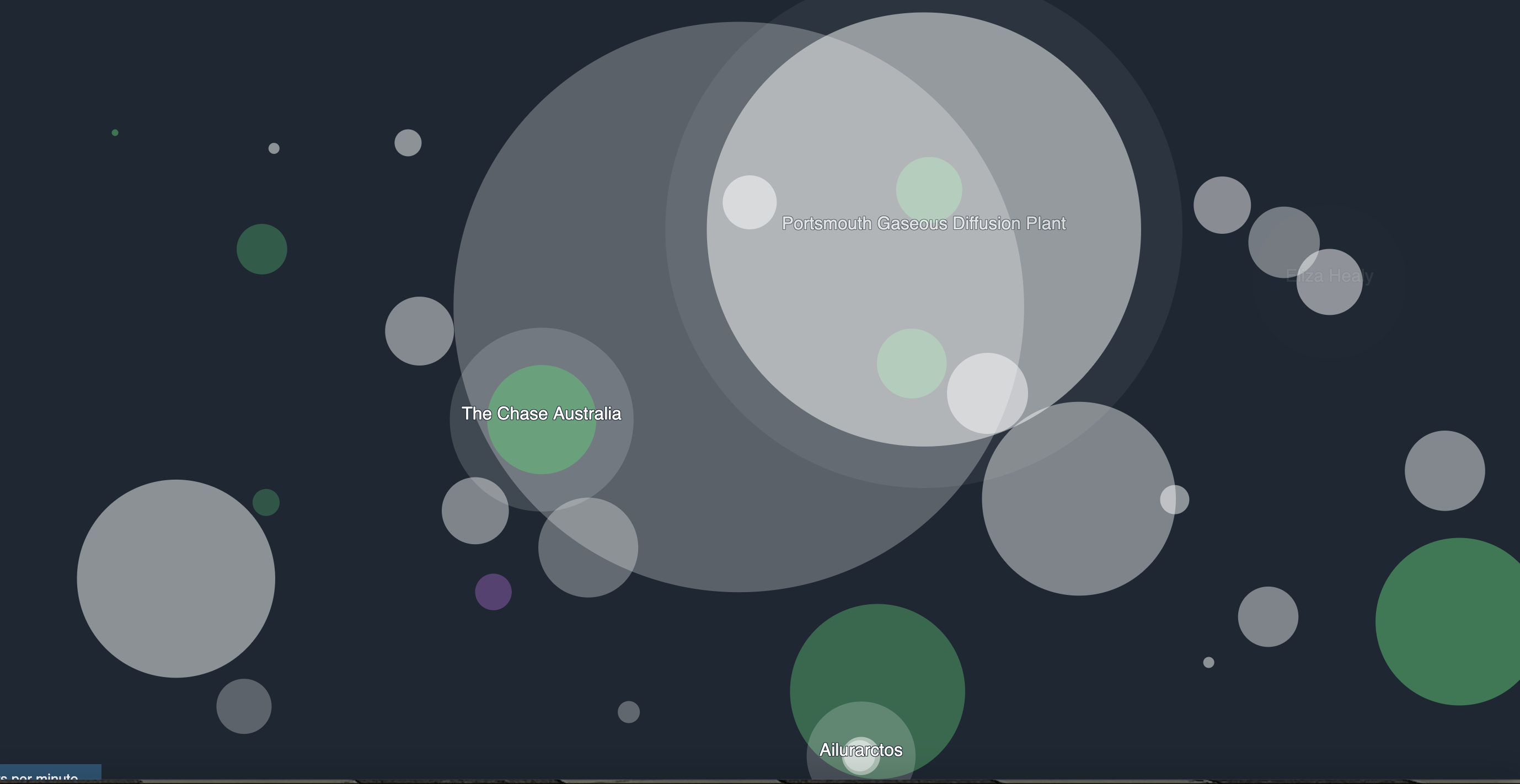

1999, and it sounds familiar. Wikipedia, of course, is one of the world’s most popular websites (the world’s most popular noncommercial one) now and an irreplaceable source of verifiable information – open to any and all. Its processes are transparent, and thanks to hackers affiliated with the project, you now can watch and listen to its edits live online:

Communities that work with Wikipedia are likely to benefit from this commitment to citation, and new collaborations that take effect around it are likely to benefit society. The Internet Archive is working with Wikipedia now, digitizing books so that links to sources in Wikipedia link all the way through to the books themselves – and render images and text on the cited pages. The reference link to a biography by Taylor Branch at the bottom of a Wikipedia article on Martin Luther King, Jr., for example, now hotlinks to the readable book online at Archive.org. That work is essential. “Only the use of footnotes and the research techniques associated with them” – as Princeton historian Anthony Grafton writes – “makes it possible to resist the efforts of modern governments, tyrannical and democratic alike, to conceal the compromises they have made, the deaths they have caused, the tortures they or their allies have inflicted.… Only the use of footnotes enables historians to make their texts not monologues but conversations, in which modern scholars, their predecessors, and their subjects all take part.”

Can we take verifiability further now, especially as our epistemic crisis deepens? Can we improve citation for the medium that’s beginning to overtake us all, which is video? Can we make resources on the web – also a new thing – verifiable? What is a citation like in a … podcast?

The great historian of the Encyclopédie, Robert Darnton, tells us in his new book, “When the printed word appeared in France in 1470, the state did not know what to make of it.” So, 700 years from now, what will tomorrow’s historians say about us? Further thoughts about how we can start more consciously collaborating with one another and producing – but immediately – for our burgeoning knowledge networks: next week.

Peter B. Kaufman works at MIT Open Learning and is the author of The New Enlightenment and the Fight to Free Knowledge. This is the second of three articles. You can find the first one in the Relateds below:

Related Content:

The New Enlightenment and the Fight to Free Knowledge: Part 1

An Animated Introduction to Voltaire: Enlightenment Philosopher of Pluralism & Tolerance

Social Media in the Age of Enlightenment and Revolution

i have been reading this essay in conjunction with chapter two of the book being promoted while at work and i feel distracted by what is going on around me and also conflicted with my interest in the material, i keep thinking how much one of those brochures would fetch today at an auction while reminding myself of the true value of the movement being covered and promoted here, the availability of knowledge.

i am still at work. i wonder how much i would get if i owned all volumes of the original Encyclopédie?