If you are a regular Open Culture reader, you’ve probably seen our many posts on Hilma af Klint, the Swedish abstract painter who might have been recognized, before Wassily Kandinsky, as the first 20th century abstractionist; that is, if she had shown any of her work before her death in obscurity in 1944 (the same year that Kandinsky died, it happens). Instead, af Klint instructed that her paintings not be exhibited until twenty years after her death. Then, another 22 years went by before anyone would see her enigmatic canvases. They first went on display in a 1986 Los Angeles show called, after Kandinsky, “The Spiritual in Art.”

Comparisons seem inevitable, but where the great Russian abstractionist theorized about art and spirit, af Klint encountered it in person, she claimed in her Theosophical accounts, in which she writes of meeting five “high masters” in a séance and receiving instructions for her new style. She was a channel, a vessel, and a medium for the spirits, as she saw it.

“The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless, I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.” She showed her paintings to occultist Rudolph Steiner, who told her to hide them away for the next half century. Discouraged she stopped painting for four years.

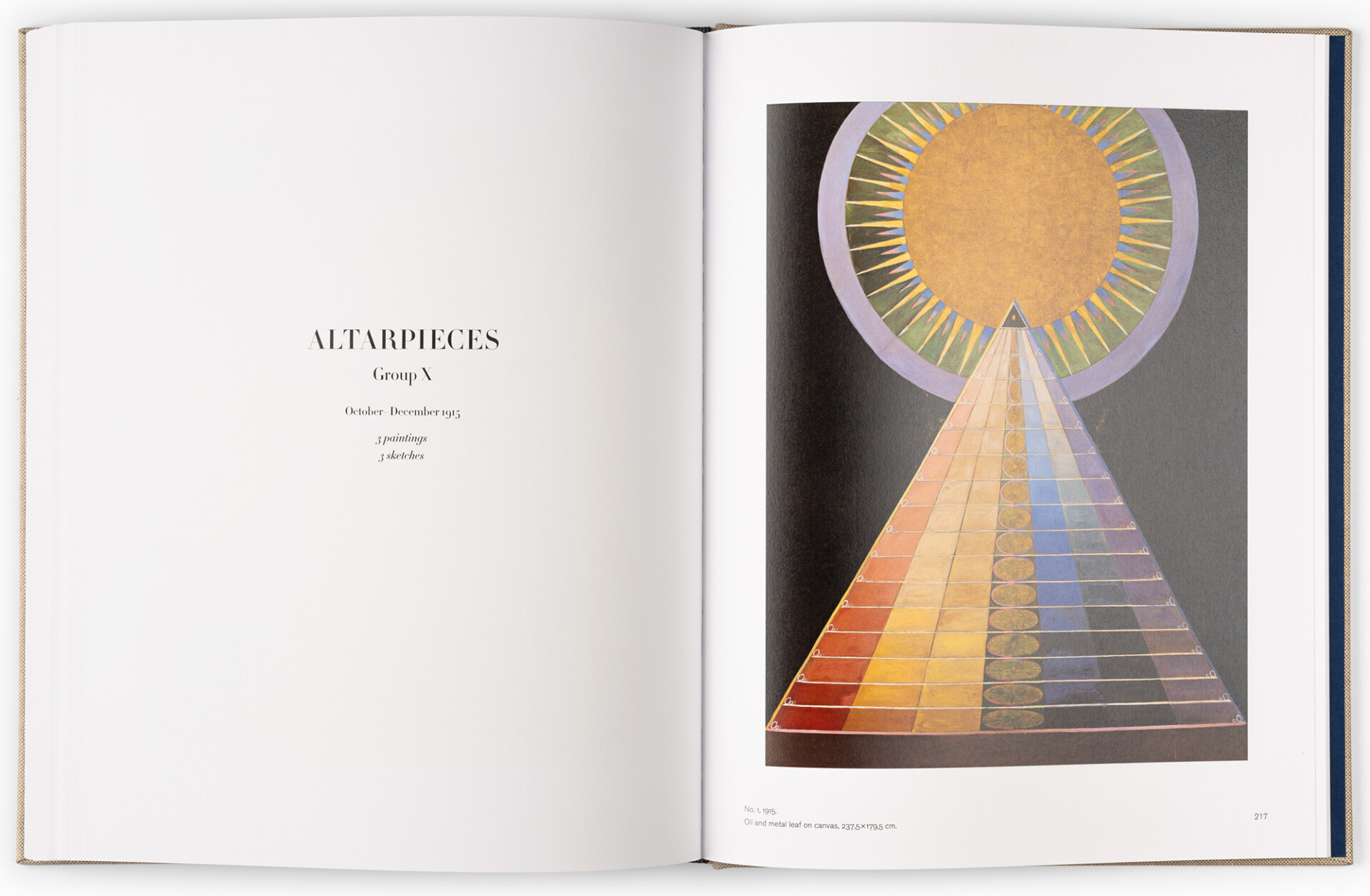

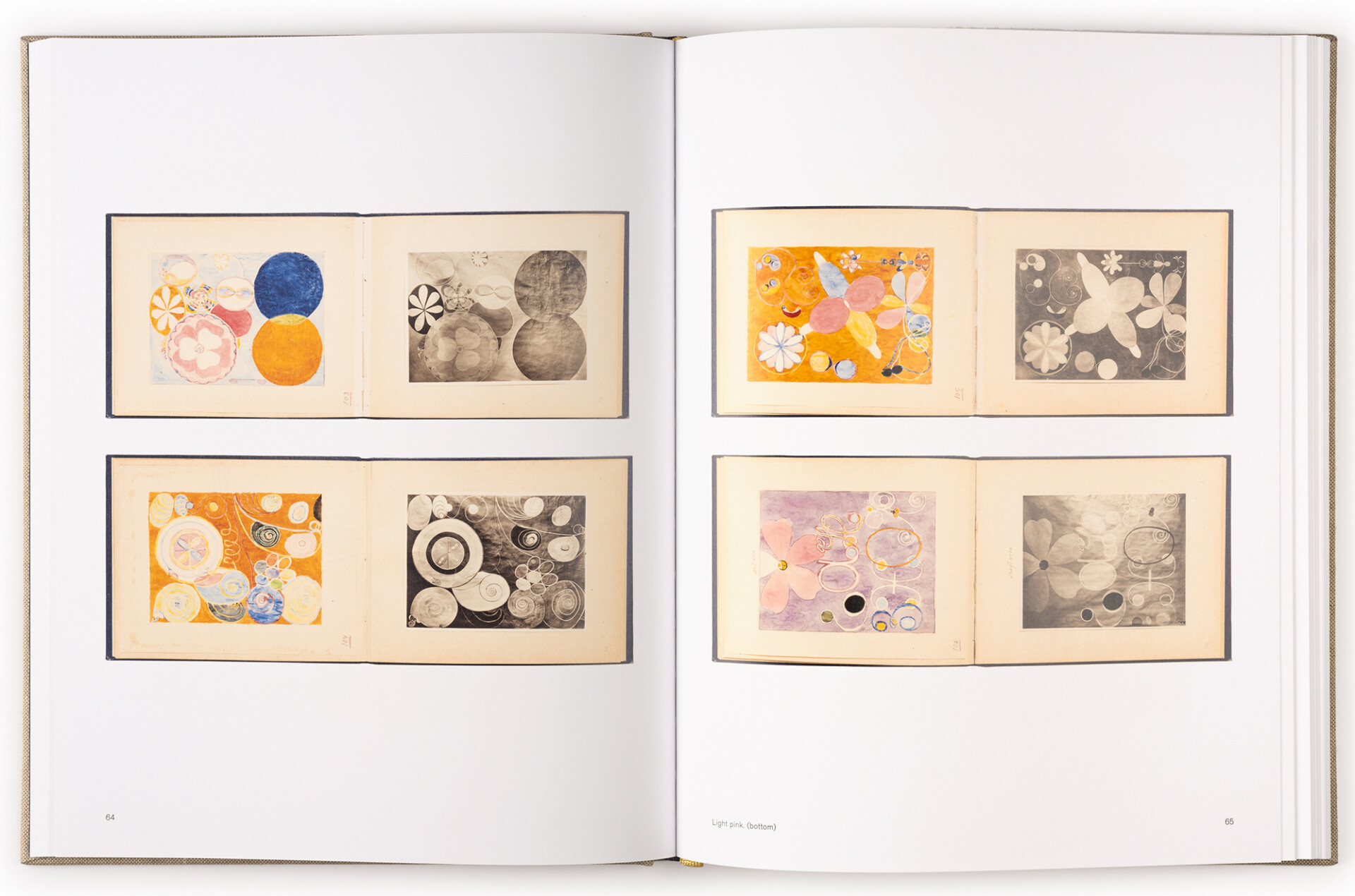

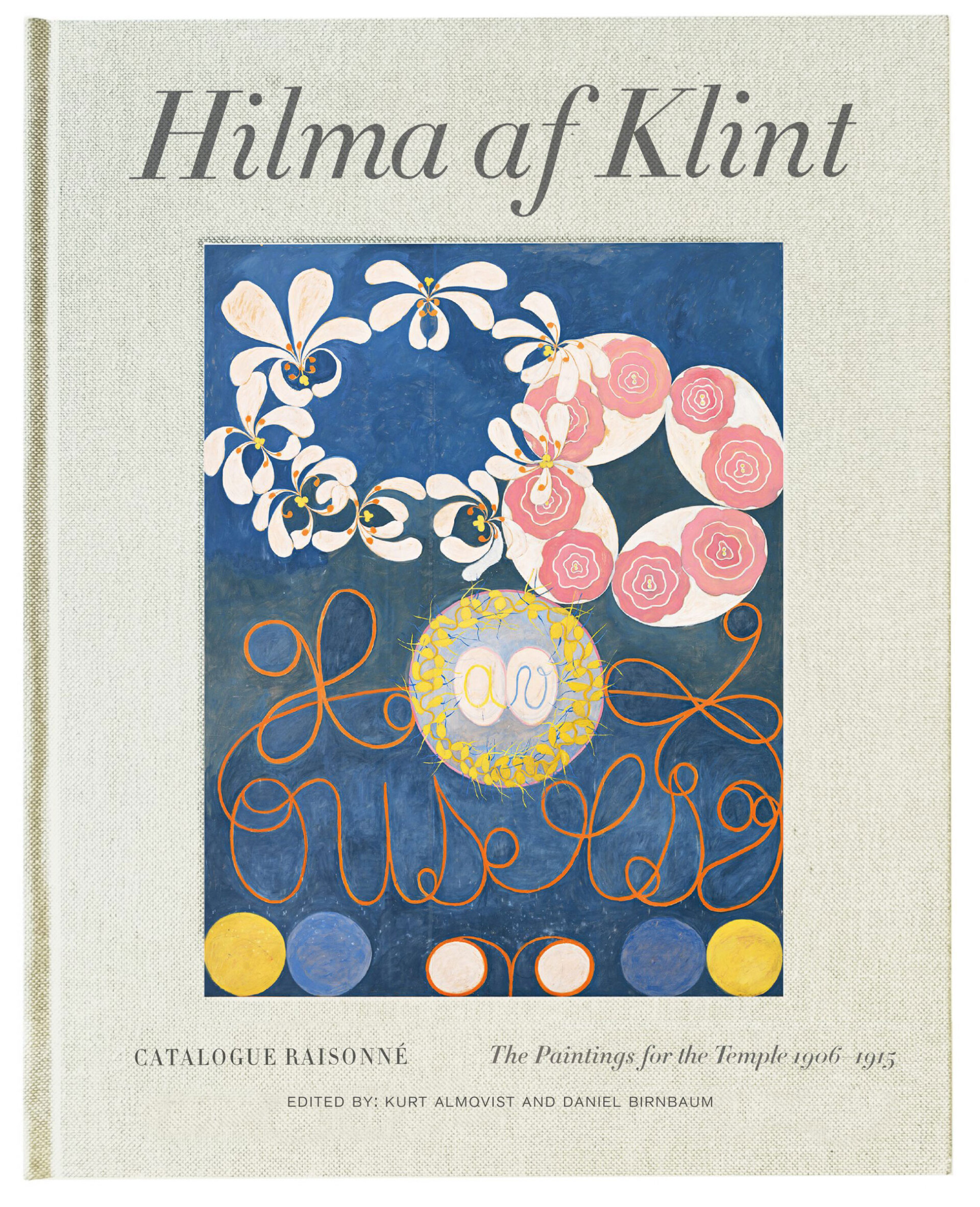

“Af Klint spent her time tending to her blind, dying mother,” writes Dangerous Minds. “She then returned to painting but kept herself and more importantly her work removed from the world.” She was not in conversation with other modern artists. She was in conversation with an unseen world, her own psyche, and a small group of women with whom she regularly conducted séances. Throughout her life, “the prolific Swedish artist created more than 1,600 works,” Grace Ebert writes at Colossal, “an impressive output now collected in Hilma AF Klint: The Complete Catalogue Raisonné: Volumes I‑VII.”

The seven-volume series, published by Bokförlaget Stolpe, “is organized both chronologically and by theme, beginning with the spiritual sketches af Klint made in conjunction with The Five, a group of women who attended séances in hopes of obtaining messages from the dead.” “What makes [af Klint’s] art interesting,” says Daniel Birnbaum, co-editor of the collection, “is that the works are highly interconnected.” Such a comprehensive accounting, a “catalogue raisonné,” is necessary “to see the different cycles, motifs, and symbols that recur in a fascinating way.”

We see such recurring patterns in the work of af Klint’s avant-garde contemporaries, as well, of course, especially in her very famous contemporary Kandinsky. But who knows how her esoteric sources and extremely retiring nature would have been received by the avant-garde movements of her time? Given that even the most extroverted women artists in those movements—from Dada, to Surrealism, to the Bauhaus School, to Abstract Expressionism—have been left out of the story time and again, it’s likely that even had the world known of Hilma af Klint in life, she would not have been appreciated or well-remembered.

But whether we credit the actions of “high masters” or the arbitrary asynchronies of cultural history, it’s clear af Klint’s moment has finally arrived. For “the first time,” Artnet notes, her “dazzling spiritual oeuvre…. will be presented in its totality.”

via Colossal

Related Content:

The Life & Art of Hilma Af Klint: A Short Art History Lesson on the Pioneering Abstract Artist

New Hilma af Klint Documentary Explores the Life & Art of the Trailblazing Abstract Artist

Discover Hilma af Klint: Pioneering Mystical Painter and Perhaps the First Abstract Artist

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I have a catalog of Helma AF Clint, the paintings for the temple 1906 to 1915. There is a number two on the side of the book indicating it’s a second volume. Can anyone give me the title of the first volume and where I could purchase it Thank you.