Photo by C. Fritz, Muséum d’Histoire naturelle de Toulouse

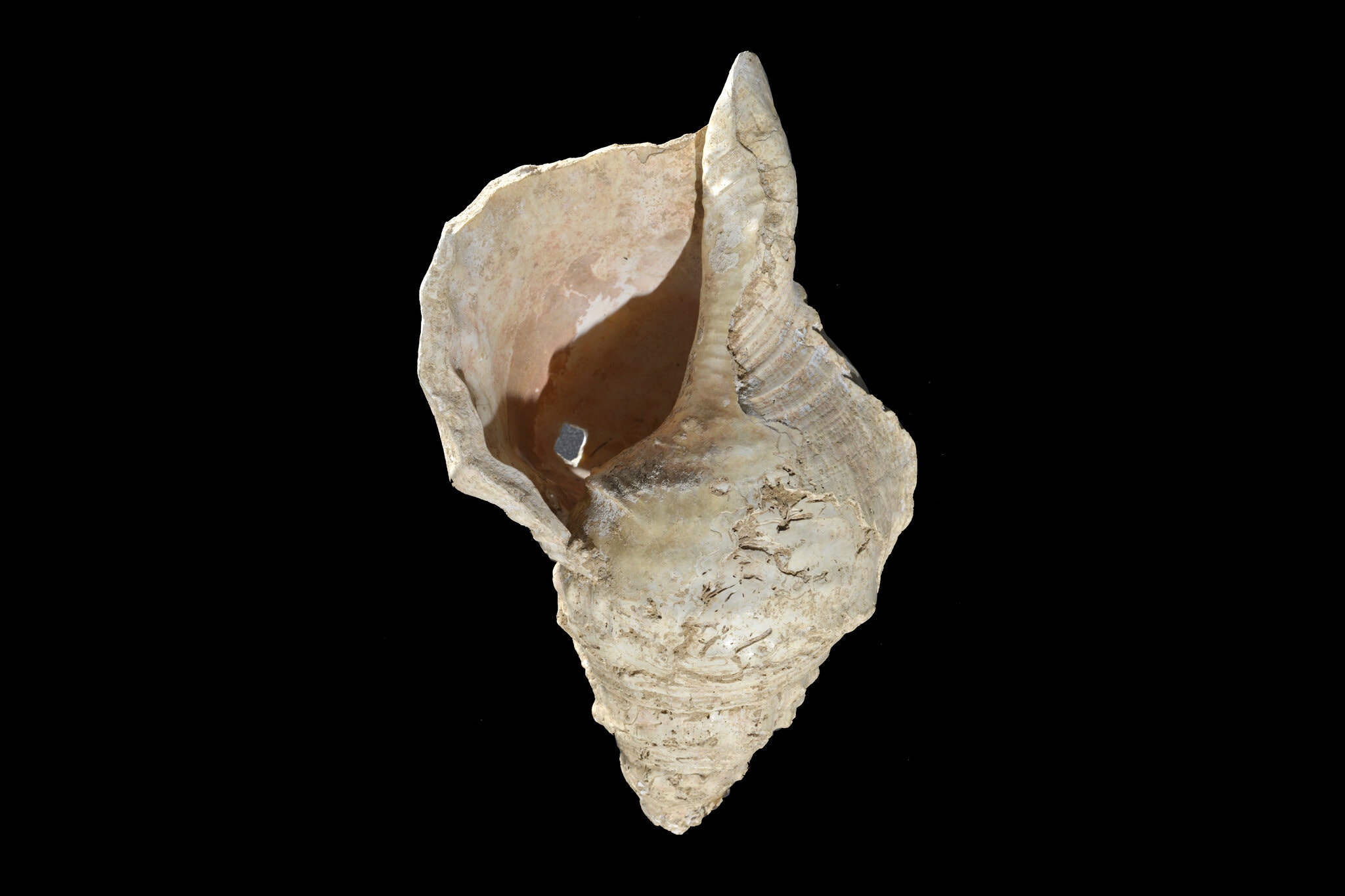

Brian Eno once defined art as “everything you don’t have to do.” But just because humans can live without art doesn’t mean we should—or that we ever have—unless forced by exigent circumstance. Even when we spent most of our time in the business of survival, we still found time for art and music. Marsoulas Cave, for example, “in the foothills of the French Pyrenees, has long fascinated researchers with its colorful paintings depicting bison, horses and humans,” Katherine Kornei writes at The New York Times. This is also where an “enormous tan-colored conch shell was first discovered, an incongruous object that must have been transported from the Atlantic Ocean, over 150 miles away.”

The 18,000-year-old shell’s 1931 discoverers assumed it must have been a large ceremonial cup, and it “sat for over 80 years in the Natural History Museum of Toulouse.” Only recently, in 2016, did researchers suspect it could be a musical instrument. Philippe Walter, director of the Laboratory of Molecular and Structural Archeology at the Sorbonne, and Carole Fritz, who leads prehistoric art research at the French National Center for Scientific Research, rediscovered the shell, as it were, when they revised old assumptions using modern imaging technology.

Fritz and her colleagues had studied the cave’s art for 20 years, but only understood the shell’s peculiarities after they made a 3D digital model. “When Walter placed the conch into a CT scan,” writes Lina Zeldovich at Smithsonian, “he indeed found many curious human touches. Not only did the ancient artists deliberately cut off the tip, but they also punctured or drilled round holes through the shell’s coils, through which they likely inserted a small tube-like mouthpiece.” The team also used a medical camera to look closely at the shell’s interior and examine unusual formations. Kornei describes the shell further:

This shell might have been played during ceremonies or used to summon gatherings, said Julien Tardieu, another Toulouse researcher who studies sound perception. Cave settings tend to amplify sound, said Dr. Tardieu. “Playing this conch in a cave could be very loud and impressive.”

It would also have been a beautiful sight, the researchers suggest, because the conch is decorated with red dots — now faded — that match the markings found on the cave’s walls.

The decoration on the shell looks similar to an image of a bison on the cave wall, suggesting it may have been played near that painting for some reason. The conch resembles similar “seashell horns” found in New Zealand and Peru, but it is much, much older. It may have originated in Spain, along with other objects found in the cave, and may have traveled with its owners or been exchanged in trade, explains archeologist Margaret W. Conkey at the University of California, who adds, writes Zeldovich, that “the Magdalenian people also valued sensory experiences, including those produced by wind instruments.

Many thousands of years later, we too can hear what those early humans heard in their cave: musicologist Jean-Michel Court gave a demonstration, producing the three notes above, which are close to C, C‑sharp and D. The shell may have had more range, and been more comfortable to play, with its mouthpiece, likely made of a hollow bird bone. The shell is hardly the oldest instrument in the world. Some are tens of thousands of years older. But it is the oldest of its kind. Whatever its prehistoric owners used it for—a call in a hunt, stage religious ceremonies, or a celebration in the cave—it is, like every ancient instrument and artwork, only further evidence of the innate human desire to create.

Related Content:

Hear the World’s Oldest Instrument, the “Neanderthal Flute,” Dating Back Over 43,000 Years

A Modern Drummer Plays a Rock Gong, a Percussion Instrument from Prehistoric Times

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply