“Either the wallpaper goes, or I do.” —Oscar Wilde

Looking to repel bed bugs and rats?

Decorate your bedroom à la Napoleon’s final home on the damp island of Saint Helena.

Those in a position to know suggest that vermin shy away from yellowish-greens such as that favored by the Emperor because they “resemble areas of intense lighting.”

We’d like to offer an alternate theory.

Could it be that the critters’ ancestors passed down a cellular memory of the perils of arsenic?

Napoleon, like thousands of others, was smitten with a hue known as Scheele’s Green, named for Carl Wilhelm Scheele, the German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist who discovered oxygen, chlorine, and unfortunately, a gorgeous, toxic green pigment that’s also a cupric hydrogen arsenite.

Scheele’s Green, aka Schloss Green, was cheap and easy to produce, and quickly replaced the less vivid copper carbonate based green dyes that had been in use prior to the mid 1770s.

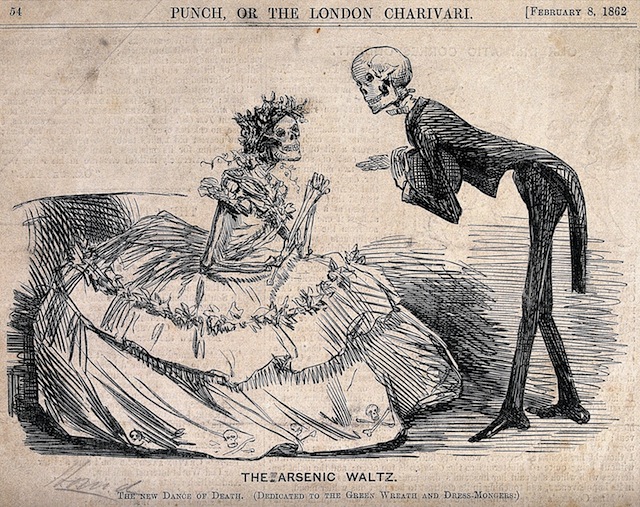

The color was an immediate hit when it made its appearance, showing up in artificial flowers, candles, toys, fashionable ladies’ clothing, soap, beauty products, confections, and wallpaper.

A month before Napoleon died, he included the following phrase in his will: My death is premature. I have been assassinated by the English oligopoly and their hired murderer…”

His exit at 51 was indeed untimely, but perhaps the wallpaper, and not the English oligopoly, is the greater culprit, especially if it was hung with arsenic-laced paste, to further deter rats.

When Scheele’s Green wallpaper, like the striped pattern in Napoleon’s bathroom, became damp or moldy, the pigment in it metabolized, releasing poisonous arsenic-laden vapors.

Napoleon’s First Valet Louis-Joseph Marchand recalled the “childish joy” with which the emperor jumped into the tub where he relished soaking for long spells:

The bathtub was a tremendous oak chest lined with lead. It required an exceptional quantity of water, and one had to go a half mile away and transport it in a barrel.

Baths also figured in Second Valet Louis Étienne Saint-Denis’ recollections of his master’s illness:

His remedies consisted only of warm napkins applied to his side, to baths, which he took frequently, and to a diet which he observed from time to time.

Saint-Denis’s recall seems to have had some lacunae. According to a post in conjunction with the American Museum of Natural History’s Power of Poison exhibit:

In Napoleon’s case, arsenic was likely just one of many compounds taxing an already troubled system. In the course of treatments for a variety of symptoms—swollen legs, abdominal pain, jaundice, vomiting, weakness—Napoleon was subjected to a smorgasbord of other toxic substances. He was said to consume large amounts of a sweet apricot-based drink containing hydrocyanic acid. He had been given tarter emetic, an antimonal compound, by a Corsican doctor. (Like arsenic, antimony would also help explain the preserved state of his body at exhumation.) Two days before his death, his British doctors gave him a dose of calomel, or mercurous chloride, after which he collapsed into a stupor and never recovered.

As Napoleon was vomiting a blackish liquid and expiring, factory and garment workers who handled Scheele’s Green dye and its close cousin, Paris Green, were suffering untold mortifications of the flesh, from hideous lesions, ulcers and extreme gastric distress to heart disease and cancer.

Fashion-first women who spent the day corseted in voluminous green dresses were keeling over from skin-to-arsenic contact. Their seamstresses’ green fingers were in wretched condition.

In 2008, an Italian team tested strands of Napoleon’s hair from four points in his life—childhood, exile, his death, and the day thereafter. They determined that all the samples contained roughly 100 times the arsenic levels of contemporary people in a control group.

Napoleon’s son and wife, Empress Josephine, also had noticeably elevated arsenic levels.

Had we been alive and living in Europe back then, ours likely would have been too.

All that green!

But what about the wallpaper?

A scrap purportedly from the dining room, where Napoleon was relocated shortly before death, was found by a woman in Norfolk, England, pasted into a family scrapbook above the handwritten caption, This small piece of paper was taken off the wall of the room in which the spirit of Napoleon returned to God who gave it.

In 1980, she contacted chemist David Jones, whom she had recently heard on BBC Radio discussing vaporous biochemistry and Victorian wallpaper. She agreed to let him test the scrap using non-destructive x‑ray fluorescence spectroscopy. The result?

.12 grams of arsenic per square meter. (Wallpapers containing 0.6 to 0.015 grams per square meter were determined to be hazardous.)

Dr. Jones described watching the arsenic levels peaking on the lab’s print out as “a crazy, wonderful moment.” He reiterated that the house in which Napoleon was imprisoned was “notoriously damp,” making it easy for a 19th century fan to peel off a souvenir in “an inspired act of vandalism.”

Death by wallpaper and other environmental factors is definitely less cloak and dagger than assassination by the English oligopoly, hired murderer, and other conspiracy theories that had thrived on the presence of arsenic in samples of Napoleon’s hair.

As Dr. Jones recalled:

…several historians were upset by my claim that it was all an accident of decor…Napoleon himself feared he was dying of stomach cancer, the disease which had killed his father; and indeed his autopsy revealed that his stomach was very damaged. It had at least one big ulcer…My feeling is that Napoleon would have died in any case. His arsenical wallpaper might merely have hastened the event by a day or so. Murder conspiracy theorists will have to find new evidence!

We can’t resist mentioning that when the emperor was exhumed and shipped back to France, 19 years after his death, his corpse showed little or no decomposition.

Green continues to be a noxious color when humans attempt to reproduce it in the physical realm. As Alice Rawthorn observed The New York Times:

The cruel truth is that most forms of the color green, the most powerful symbol of sustainable design, aren’t ecologically responsible, and can be damaging to the environment.

Take a deeper dive into Napoleon’s wallpaper with an educational packet for educators prepared by chemist David Jones and Hendrik Ball.

Related Content:

Why Is Napoleon’s Hand Always in His Waistcoat?: The Origins of This Distinctive Pose Explained

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She most recently appeared as a French Canadian bear who travels to New York City in search of food and meaning in Greg Kotis’ short film, L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply