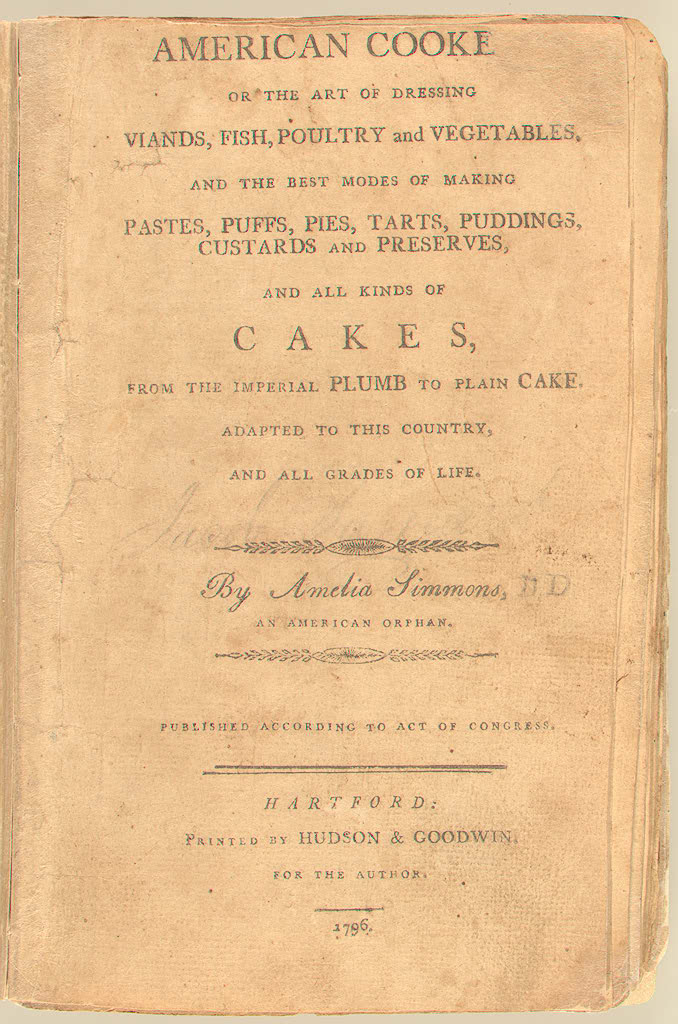

Image via Wikimedia Commons

On the off chance Lin-Manuel Miranda is casting around for source material for his next American history-based blockbuster musical, may we suggest American Cookery by “poor solitary orphan” Amelia Simmons?

First published in 1796, at 47 pages (nearly three of them are dedicated to dressing a turtle), it’s a far quicker read than the fateful Ron Chernow Hamilton biography Miranda impulsively selected for a vacation beach read.

Slender as it is, there’s no shortage of meaty material:

Calves Head dressed Turtle Fashion

Soup of Lamb’s Head and Pluck

Fowl Smothered in Oysters

Tongue Pie

Foot Pie

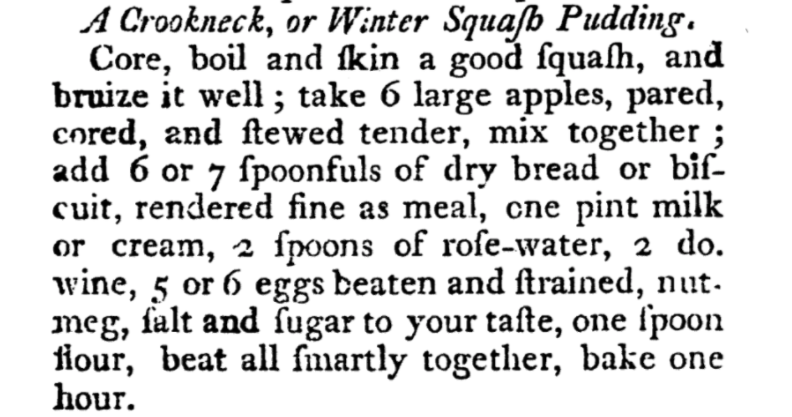

Modern chefs may find some of the first American cookbook’s methods and measurements take some getting used to.

We like to cook, but we’re not sure we possess the wherewithal to tackle a Crookneck or Winter Squash Pudding.

We’ve never been called upon to “perfume” our “whipt cream” with “musk or amber gum tied in a rag.”

And we wouldn’t know a whortleberry if it bit us in the whitpot.

The book’s full title is an indication of its mysterious author’s ambitions for the new country’s culinary future:

American Cookery, or the art of dressing viands, fish, poultry, and vegetables, and the best modes of making pastes, puffs, pies, tarts, puddings, custards, and preserves, and all kinds of cakes, from the imperial plum to plain cake: Adapted to this country, and all grades of life.

As Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald write in an essay for What It Means to Be an American, a “national conversation hosted by the Smithsonian and Arizona State University,” American Cookery managed to straddle the refined tastes of Federalist elites and the Jeffersonians who believed “rustic simplicity would inoculate their fledgling country against the corrupting influence of the luxury to which Britain had succumbed”:

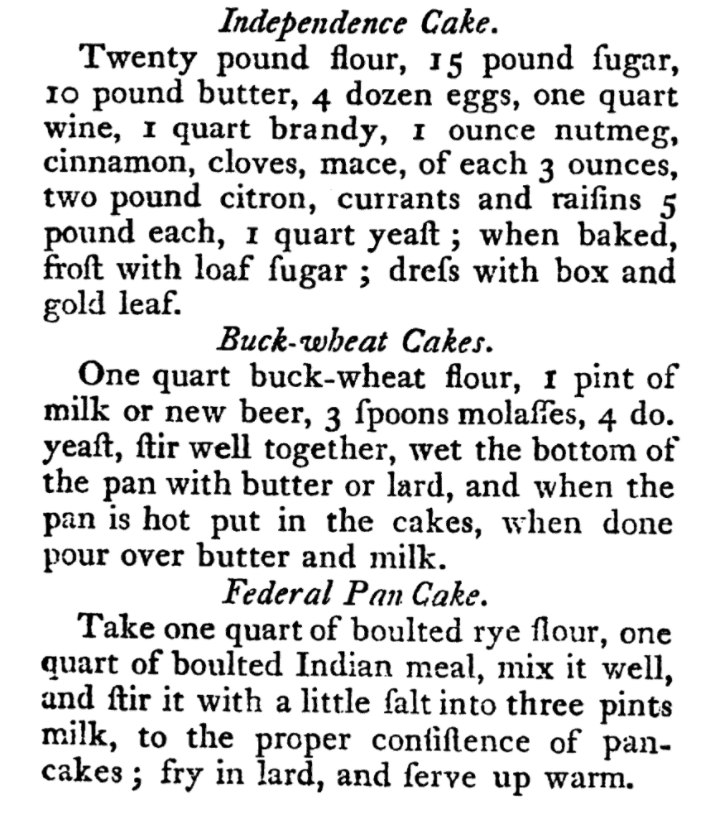

The recipe for “Queen’s Cake” was pure social aspiration, in the British mode, with its butter whipped to a cream, pound of sugar, pound and a quarter of flour, 10 eggs, glass of wine, half-teacup of delicate-flavored rosewater, and spices. And “Plumb Cake” offered the striving housewife a huge 21-egg showstopper, full of expensive dried and candied fruit, nuts, spices, wine, and cream.

Then—mere pages away—sat johnnycake, federal pan cake, buckwheat cake, and Indian slapjack, made of familiar ingredients like cornmeal, flour, milk, water, and a bit of fat, and prepared “before the fire” or on a hot griddle. They symbolized the plain, but well-run and bountiful, American home. A dialogue on how to balance the sumptuous with the simple in American life had begun.

(Hamilton fans will please note that the cake for the 1780 Schuyler-Hamilton wedding leaned more toward the former than anything in the johnnycake / slapjack vein…)

American Cookery is one of nine 18th-century titles to make the Library of Congress’ list of 100 Books That Shaped America:

This cornerstone in American cookery is the first cookbook of American authorship to be printed in the United States. Numerous recipes adapting traditional dishes by substituting native American ingredients, such as corn, squash and pumpkin, are printed here for the first time. Simmons’ “Pompkin Pudding,” baked in a crust, is the basis for the classic American pumpkin pie. Recipes for cake-like gingerbread are the first known to recommend the use of pearl ash, the forerunner of baking powder.

Students of Women’s History will find much to chew on in the second edition of American Cookery as well, though they may find a few spoonfuls of pearl ash dissolved in water necessary to settle upset stomachs after reading Simmons’ introduction.

Stavely and Fitzgerald observe how “she thanks the fashionable ladies,” or “respectable characters,” as she calls them, who have patronized her work, before returning to her main theme: the “egregious blunders” of the first edition, “which were occasioned either by the ignorance, or evil intention of the transcriber for the press.”

Ultimately, all of her problems stem from her unfortunate condition; she is without “an education sufficient to prepare the work for the press.” In an attempt to sidestep any criticism that the second edition might come in for, she writes: “remember, that it is the performance of, and effected under all those disadvantages, which usually attend, an Orphan.”

Read the second edition of American Cookery here. (If the archaic font troubles your eyes, a plainer version is here.) A facsimile edition of American Cookery can be purchased online.

Listen to a LibriVox audio recording of American Cookery here.

Related Content:

An Archive of 3,000 Vintage Cookbooks Lets You Travel Back Through Culinary Time

Recipes from the Kitchen of Georgia O’Keeffe

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She most recently appeared as a French Canadian bear who travels to New York City in search of food and meaning in Greg Kotis’ short film, L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

That recipe says “Winter Squash,” not “Winter Squab.”

You’re confused by the old-timey typeface.

thank you. where are the fact checkers?

The recipe is quite clearly printed as “Winter Squash,” not “Winter Squab,” and the title of the book is “American Cooke” (i.e., “American Cook,” in modern spelling), NOT “American Cookery.”

the “ry” were obscured by a blemish in the original’s cover. If you look closely, you can see the damage to the paper.