Of all the varied objects of creation there is, probably, no portion that affords so much gratification and delight to mankind as plants. —Elizabeth Twining

“Who owned nature in the eighteenth century?” asks Londa Schiebinger in Plants and Empire, a study of what the Stanford historian of science calls “colonial bioprospecting in the Atlantic World.” The question was largely decided at the time by “heroic voyaging botanists” and “biopirates” who claimed the world’s natural resources as their own. The matter was settled in the next couple centuries by merchants like Thomas Twining and his descendants, proprietors of Twinings tea. Founded as Britain’s first known tea shop in 1706, the company went on to become one of the largest purveyors of teas grown in the British colonies.

One of Twining’s descendants, Elizabeth Twining, carried on the legacy as what Schiebinger calls one of many “armchair naturalists, who coordinated and synthesized collecting from sinecures in Europe,” a role often taken on by women who could not travel the world. Twining aimed, however, not to create taxonomies of the world’s plants but those of her own country in a comparative analysis.

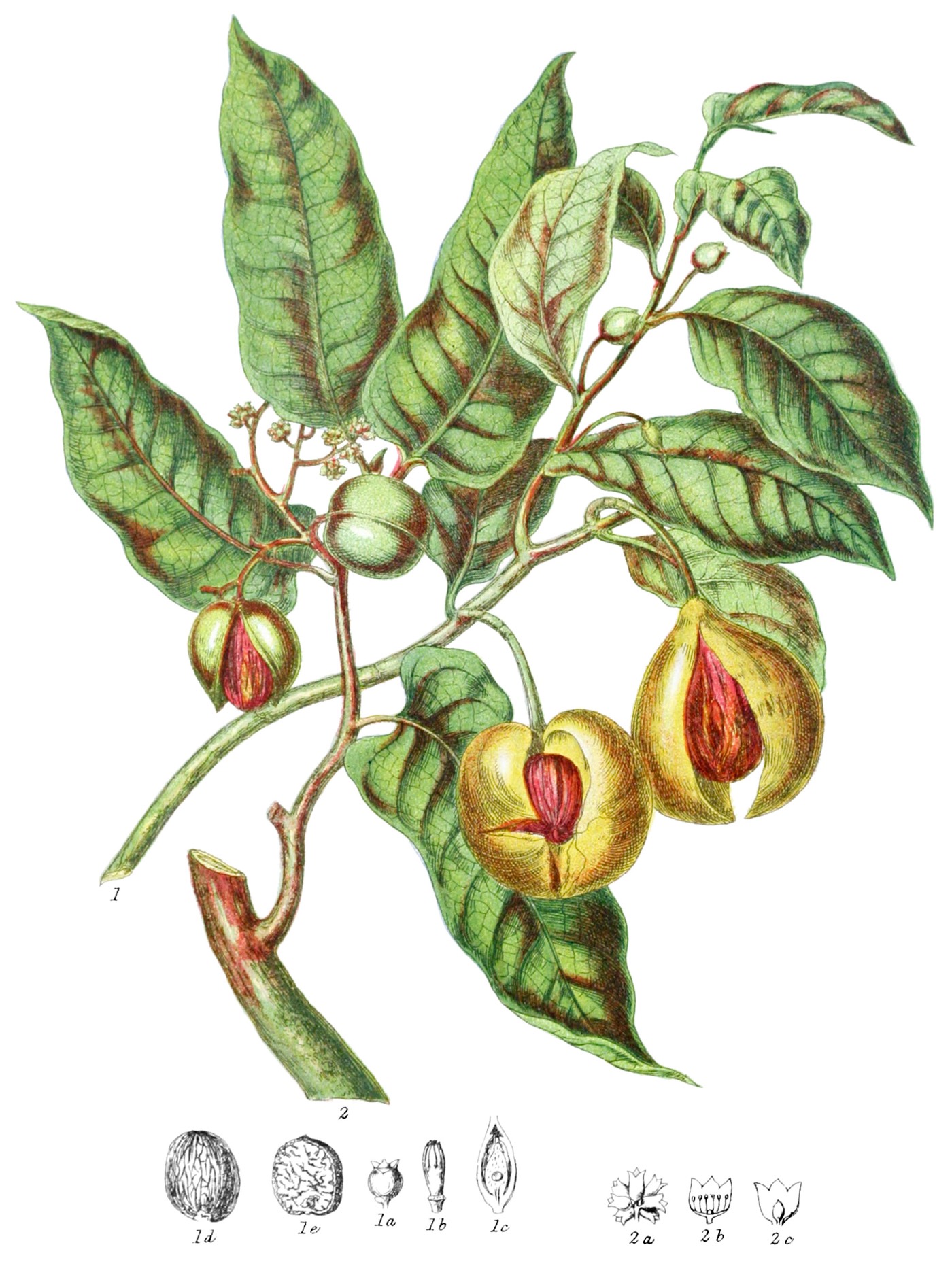

Her 1868 Illustrations of the Natural Orders of Plants, she wrote in her introduction, was “the first work which has thus done due honour to our British plants by connecting with others, and placing them whenever possible at the head of the Order to be illustrated.”

Twining’s revaluation of local British plants was in keeping with the reformist spirit of the age, and she herself was such a reformer. “Apart from her artistic endeavors,” writes Nicholas Rougeaux, Twining “was a notable philanthropist,” establishing almshouses and temperance halls, founding “mother’s meetings” in London, and helping to found the Bedford College for Women. She was inspired by Curtis’s The Botanical Magazine and “she practiced by making sketches from works in the Dulwich Picture Gallery, and toured famous museums thanks to her father’s patronage.”

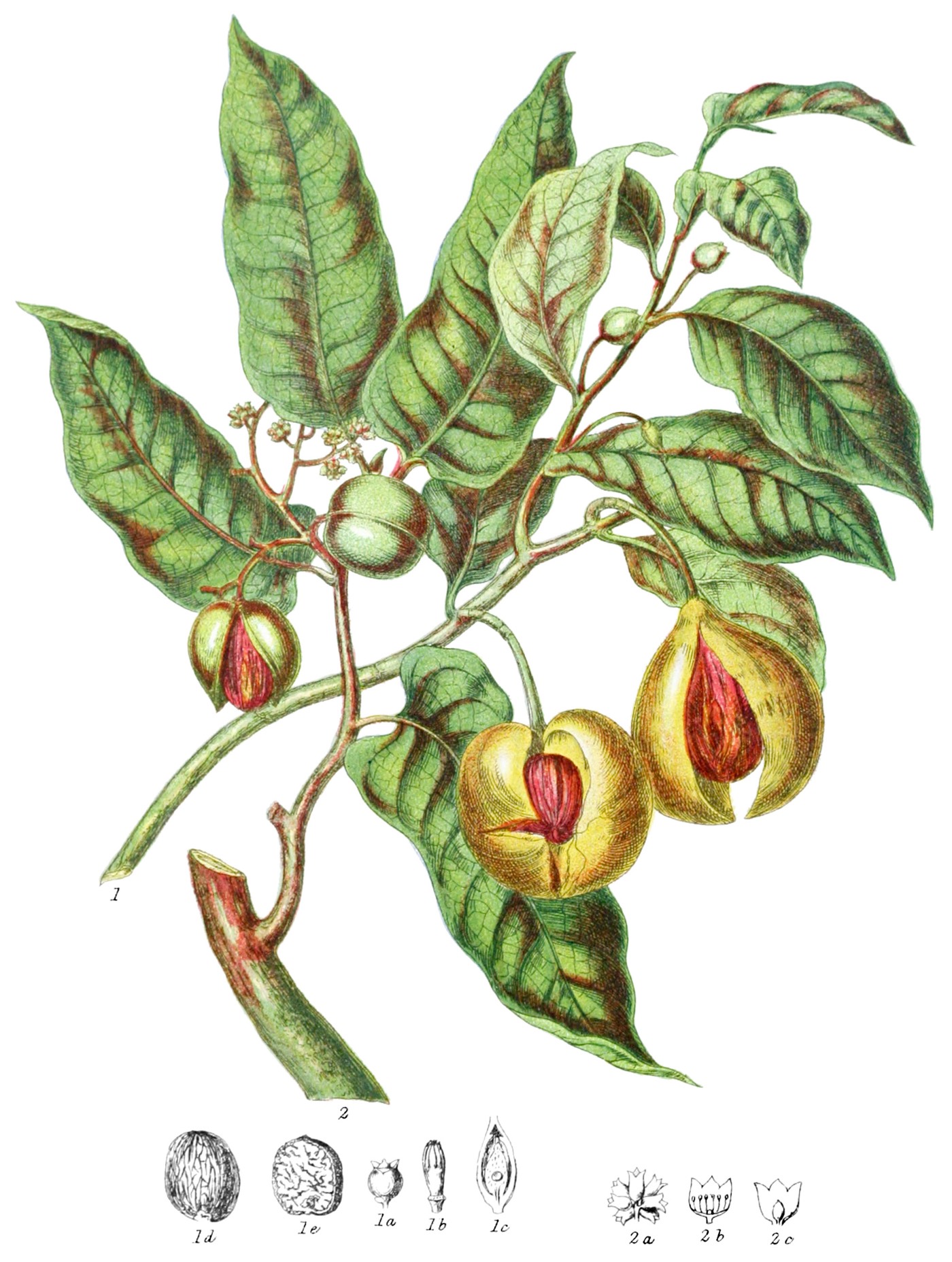

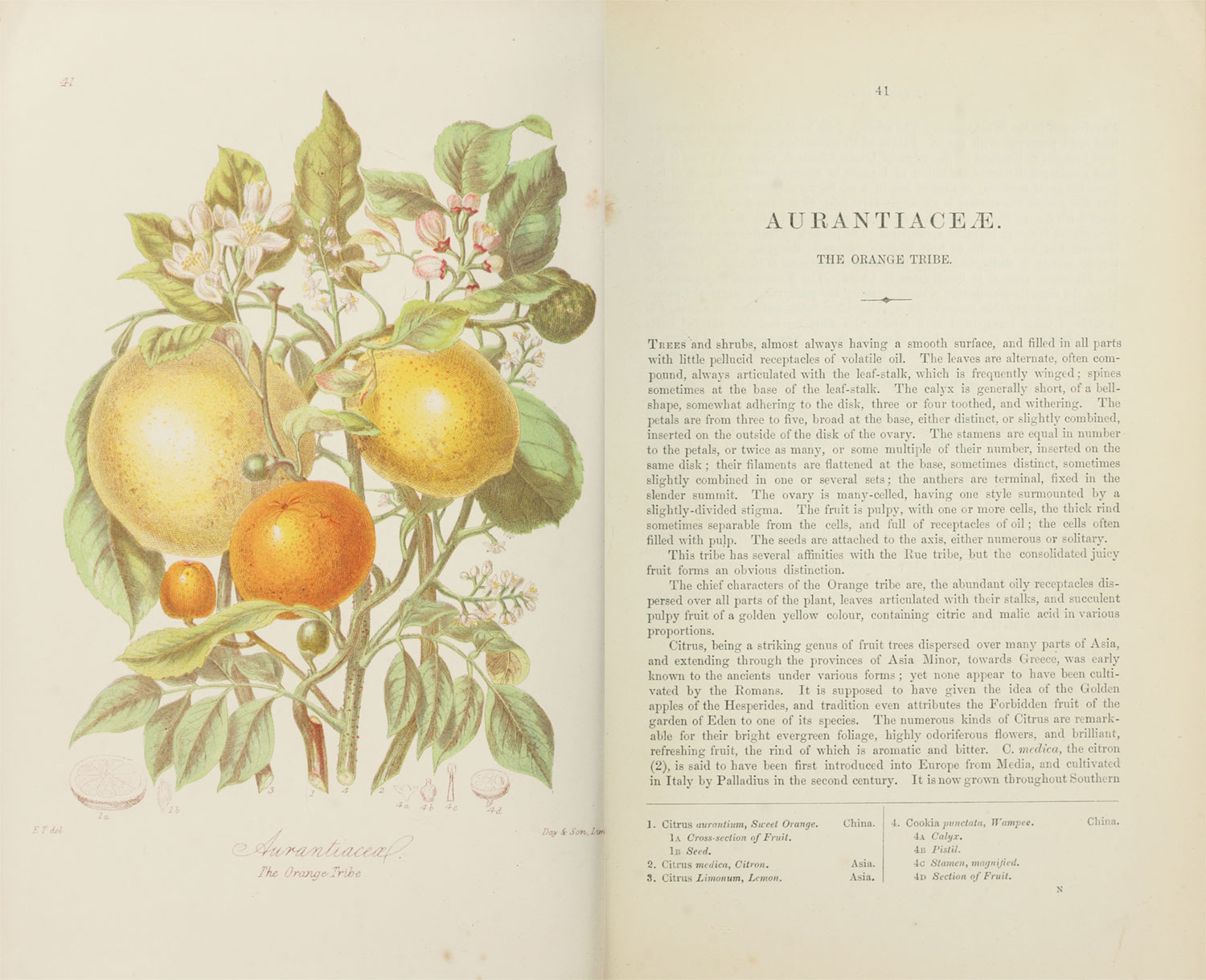

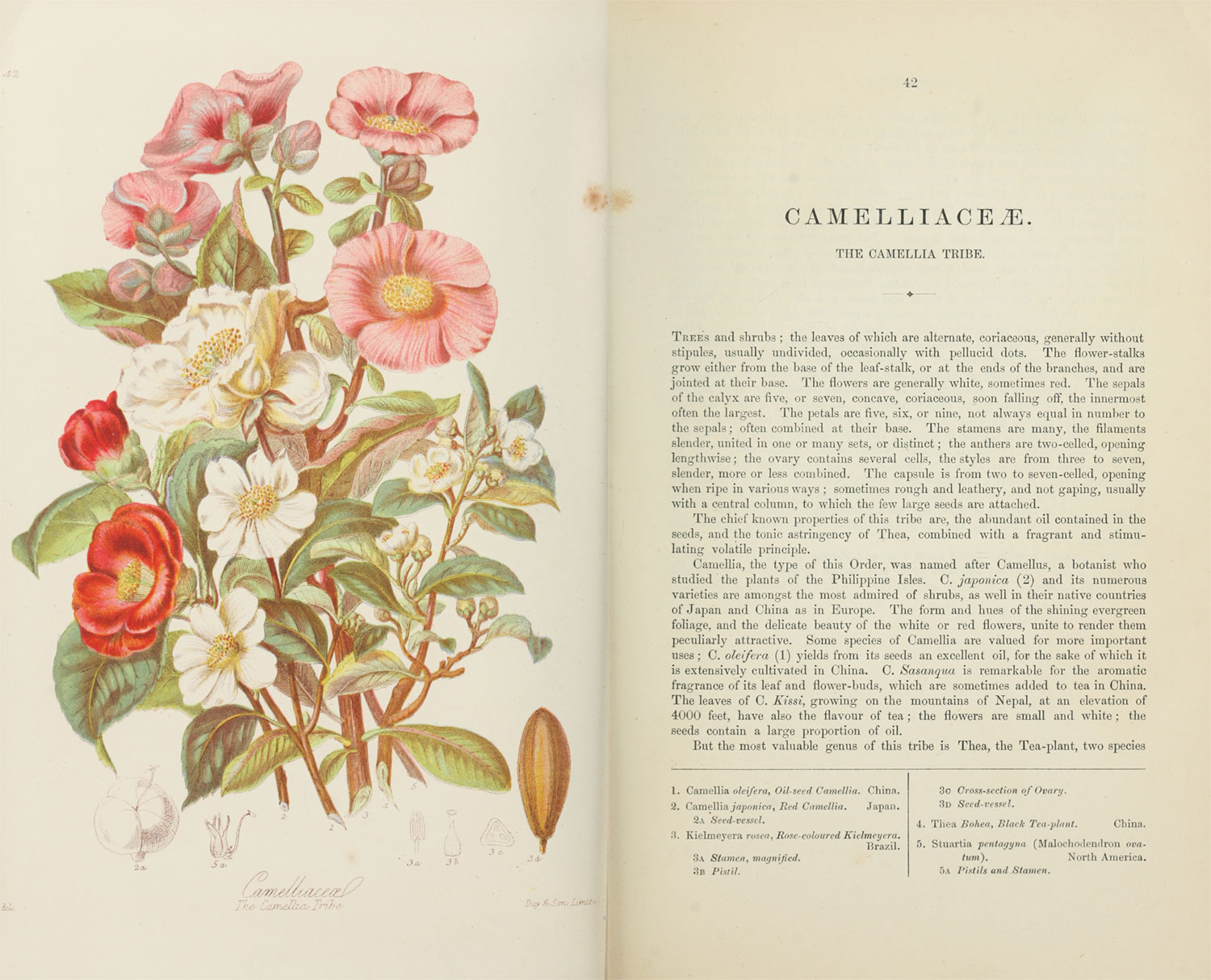

Twining authored and illustrated several botanical books, “most notably,” Rougeux writes, “the two volume Illustrations of the Natural Orders of Plants, which included a total of 160 hand-colored lithographs, royal folio, reportedly based on observation at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew and at Lexden Park in Colchester.” Rougeux has done for her work what the designer previously did for other illustrated classics of science and math (see the related links below): digitizing the illustrations and transliterating the text into a digital format, with hyperlinks and sharing features.

Rougeux’s Illustrations of the Natural Orders of Plants offers itself as “a complete reproduction and restoration… enhanced with interactive illustrations, descriptions, and posters featuring the illustrations.” The first two volumes of the original book were published in 1849 and 1855. Rougeux’s online version of the text is based on the 1868 second edition “with re-drawn illustrations based on her originals.” (See pages from the text above and below.) Rougeux’s digitized text is thus two steps removed from Twining’s original illustrations, but we can see the care and attention she put into classifying the flora of her native country.

“Twining chose to illustrate plants using the classification system created by Augustin-Pyrame de Candolle based on multiple characteristics of plants—rather than the more widely used system by Carl Linnaeus which was focused on plants’ reproductive characteristics,” notes Rougeux, “because the De Candolle system was newer and she wanted her readers to be up to date as classification systems were evolving.”

Although biological taxonomies have changed considerably since her time, Twining’s Illustrations of the Natural Orders of Plants remains an intriguing “snapshot in time” that depicts not only the latest ideas about plant classification in the mid-19th century but also the attitudes a prominent member of the British ruling class adopted toward nature as a whole. See Rougeux’s online edition of Twining’s text here.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Nobody, nowhere, draws or paints this well, anymore. What happened?!