We must fight against puddles of sauce, disordered heaps of food, and above all, against flabby, anti-virile pastasciutta. —poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

Odds are Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the father of Futurism and a dedicated provocateur, would be crestfallen to discover how closely his most incendiary gastronomical pronouncement aligns with the views of today’s low-carb crusaders.

In denouncing pasta, “that absurd Italian gastronomic religion,” his intention was to shock and criticize the bourgeoisie, not reduce bloat and inflammation.

He did, however, share the popular 21st-century view that heavy pasta meals leave diners feeling equally heavy and lethargic.

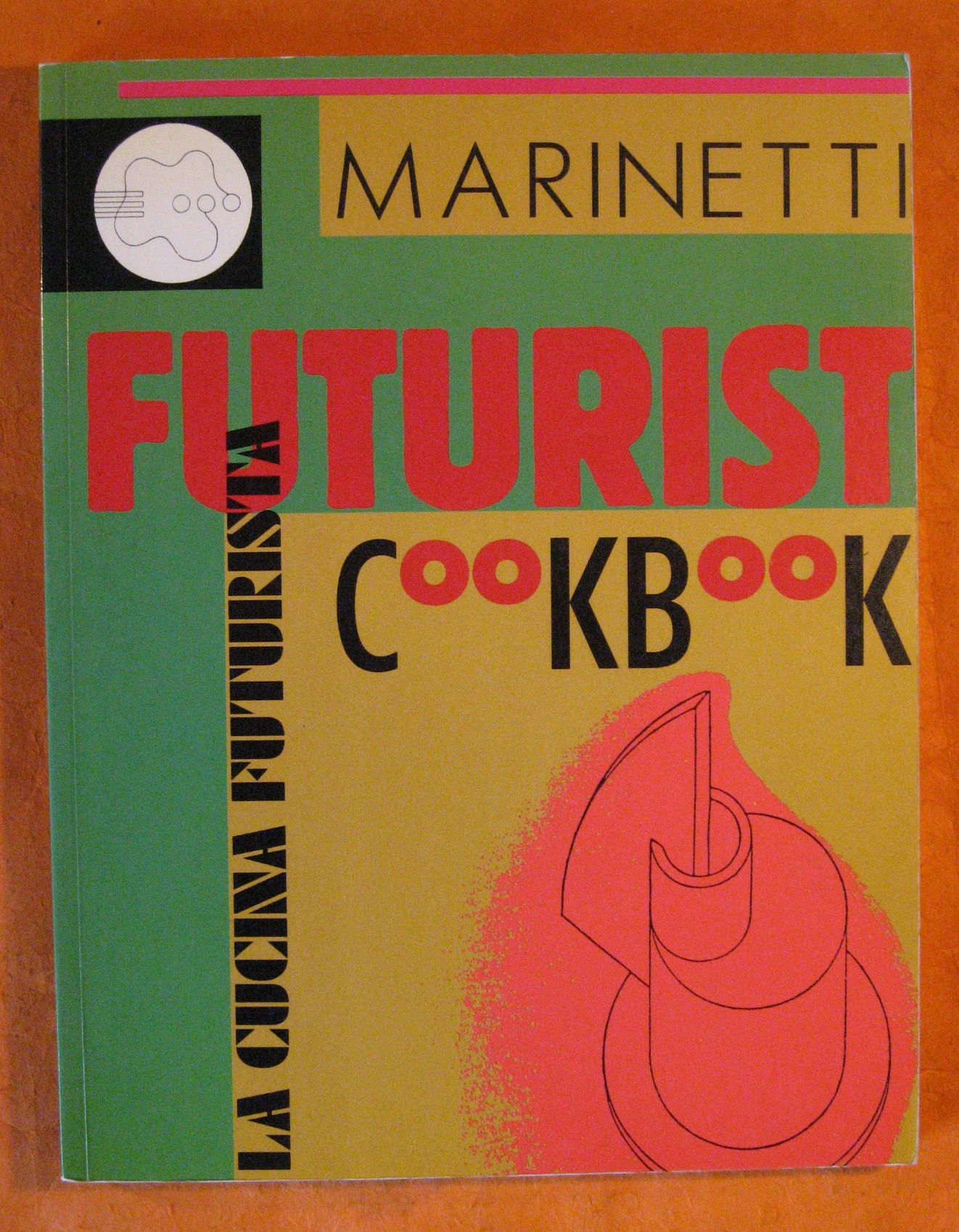

As he declared in 1930 in The Futurist Cookbook:

Futurist cooking will be free of the old obsessions with volume and weight and will have as one of its principles the abolition of pastasciutta. Pastasciutta, however agreeable to the palate, is a passéist food because it makes people heavy, brutish, deludes them into thinking it is nutritious, makes them skeptical, slow, pessimistic… Any pastascuittist who honestly examines his conscience at the moment he ingurgitates his biquotidian pyramid of pasta will find within the gloomy satisfaction of stopping up a black hole. This voracious hole is an incurable sadness of his. He may delude himself, but nothing can fill it. Only a Futurist meal can lift his spirits. And pasta is anti-virile because a heavy, bloated stomach does not encourage physical enthusiasm for a woman, nor favour the possibility of possessing her at any time.

Bombast came naturally to him. While he truly believed in the tenets of Futurism—speed, industry, technology, and the cleansing effects of war, at the expense of tradition and the past—he gloried in hyperbole, absurdity, and showy pranks.

The Futurist Cookbook reflects this, although it does contain actual recipes, with very specific instructions as to how each dish should be served. A sample:

RAW MEAT TORN BY TRUMPET BLASTS: cut a perfect cube of beef. Pass an electric current through it, then marinate it for twenty-four hours in a mixture of rum, cognac and white vermouth. Remove it from the mixture and serve on a bed of red pepper, black pepper and snow. Each mouthful is to be chewed carefully for one minute, and each mouthful is divided from the next by vehement blasts on the trumpet blown by the eater himself.

Intrepid host Trevor Dunseith documents his attempt to stage a faithful Futurist dinner party in the above video.

Guests eat salad with their hands for maximum “pre-labial tactile pleasure” before balancing oranges stuffed with antipasto on their heads to randomize the selection of each mouthful. While not all of the flavors were a hit, the party agreed that the experience was—as intended—totally novel (and 100% pasta free).

Marinetti’s anti-pasta campaign chimed with Prime Minister Benito Mussolini’s goal of eliminating Italy’s economic dependence on foreign markets—the Battle for Grain. Northern farmers could produce ample supplies of rice, but nowhere near the amount of wheat needed to support the populace’s pasta consumption. If Italians couldn’t grow more wheat, Mussolini wanted them to shift from pasta to rice.

F.T. Marinetti by W. Seldow, 1934

Marinetti agreed that rice would be the “patriotic” choice, but his desired ends were rooted in his own avant-garde art movement:

… it is not just a question of replacing pasta with rice, or of preferring one dish to another, but of inventing new foods. So many mechanical and scientific changes have come into effect in the practical life of mankind that it is also possible to achieve culinary perfection and to organize various tastes, smells and functions, something which until yesterday would have seemed absurd because the general conditions of existence were also different. We must, by continually varying types of food and their combinations, kill off the old, deeply rooted habits of the palate, and prepare men for future chemical foodstuffs. We may even prepare mankind for the not-too-distant possibility of broadcasting nourishing waves over the radio.

Futurism’s ties to fascism are not a thing to brush off lightly, but it’s also important to remember that Marinetti believed it was the artist’s duty to put forward a bold public personae. He lived to ruffle feathers.

Mission accomplished. His anti-pasta pronouncements resulted in a tumult of public indignation, both locally and in the States.

The Duke of Bovino, mayor of Naples, reacted to Marinetti’s statement that pasta is “completely hostile to the vivacious spirit and passionate, generous, intuitive soul of the Neapolitans” by saying, “The angels in Heaven eat nothing but vermicelli al pomodoro.” Proof, Marinetti sniped back, of “the unappetizing monotony of Paradise and of the life of the Angels.”

He agitated for a futuristic world in which kitchens would be stocked with ”atmospheric and vacuum stills, centrifugal autoclaves (and) dialyzers.”

His recipes, as Trevor Dunseith discovered, function better as one-time performance art than go-to dishes to add to one’s culinary repertoire.

There is a reason why Julia Child’s Coq a Vin and Tarte Tatin endure while Marinetti’s Excited Pig and Black Shirt Snack have fallen into disuse.

Uh… progress?

As Daniel A. Gross writes in the Science History Institute’s Distillations:

Marinetti supported Fascism to the extent that it too advocated progress, but his allegiance eventually wavered. To Marinetti, Roman ruins and Renaissance paintings were not only boring but also antithetical to progress. To Mussolini, by contrast, they were politically useful. The dictator drew on Italian history in his quest to build a new, powerful nation—which also led to a national campaign in food self-sufficiency, encouraging the growing and consumption of such traditional foods as wheat, rice, and grapes. The government even funded research into the nutritional benefits of wheat, with one scientist claiming whole-wheat bread boosted fertility. In short, the prewar dream of futurist food was tabled yet again.

Get your own copy of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s The Futurist Cookbook here.

via Mental Floss

Related Content:

Salvador Dalí’s 1973 Cookbook Gets Reissued: Surrealist Art Meets Haute Cuisine

Recipes from the Kitchen of Georgia O’Keeffe

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. See her as a French Canadian bear who travels to New York City in search of food and meaning in Greg Kotis’ short film, L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Who knew Ben liked his rice?!