Photo via Wikimedia Commons

“You do not really understand something unless you can explain it to your grandmother,” goes a well-known quote attributed variously to Albert Einstein, Richard Feynman, and Ernest Rutherford. No matter who said it, “the sentiment… rings true,” writes Michelle Lavery, “for researchers in all disciplines from particle physics to ecopsychology.” As Feynman discovered during his many years of teaching, it could be “the motto of all professional communicators,” The Guardian’s Russell Grossman writes, “and especially those who earn a living communicating the tricky business of science.”

Einstein became one of the world’s great science communicators by choice, not necessity, and found ways to explain his complex theories to children and the elderly alike. But perhaps, if he’d had his way, he would rather have avoided words altogether, and preferred acrobatic feats of silent daring to get his message across. We might at least conclude so from his reverence for the work of Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin was the only person Einstein wanted to meet in California during his second, 1930–31 visit to the U.S., when he was “at the height of his fame,” notes Claire Cock-Starkey at Mental Floss, “with newspapers tracking his every move and academics clamoring for explanations of his theories.”

The admiration, of course, was mutual. Their first meetings happened outside the press’s scrutiny, at Universal Studios, “where the pair took a tour and had lunch together. They hit it off straight away, sharing quick wits and curious minds.” In his autobiography, Chaplin writes that Einstein’s wife Elsa finagled an invitation to dinner at Chaplin’s house. And he “was only too happy to oblige,” Cock-Starkey writes, arranging an “intimate dinner, at which Elsa regaled him with the story of when Einstein came up with his world-changing theory, sometime around 1915.”

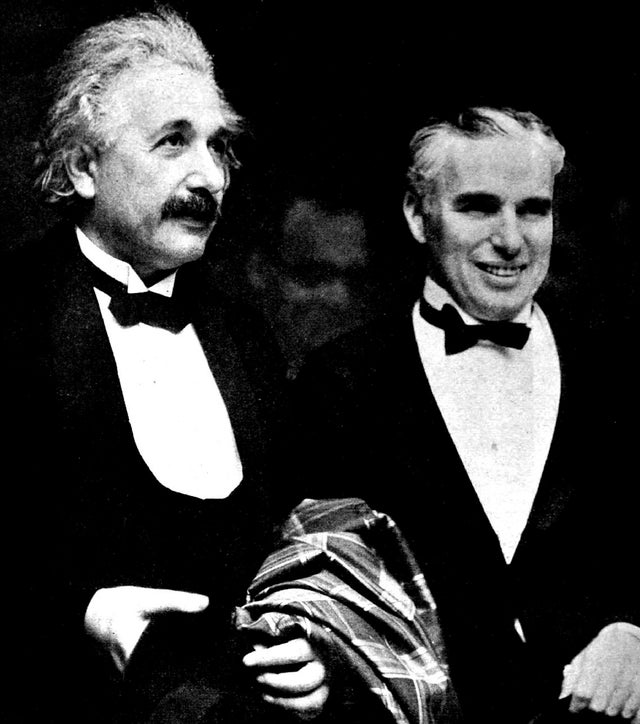

The two continued to correspond, and the big public unveiling of their friendship came when Chaplin invited Einstein to the premier of City Lights in 1931 (see photo up top) where the mega-celebrities from very different worlds were greeted by reporters, photographers, and adoring crowds. There are several recorded versions of their conversation. In one account, Einstein expressed bemusement at the cheering, and Chaplin remarked, “the people applaud me because everyone understands me, and they applaud you because no one understands you.”

Chaplin himself wrote in his 1933–34 travelogue, A Comedian Sees the World, that one of Einstein’s sons uttered the line, weeks afterward: “You are popular [because] you are understood by the masses. On the other hand, the professor’s popularity with the masses is because he is not understood.” Yet another version, circulating on the Nobel Prize’s Instagram and collecting tens of thousands of likes, has the exchange take place in a dialogue.

Einstein: “What I most admire about your art, is your universality. You don’t say a word, yet the world understands you!”

Chaplin: “True. But your glory is even greater! The whole world admires you, even though they don’t understand a word of what you say.”

Whatever they really said to each other, it’s clear Einstein saw something in Charlie Chaplin worth emulating. Chaplin left his mark on Existentialist philosophy, lending the name of his film Modern Times to Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir’s influential journal, Les Temps Modernes. He left a legacy on Beat poetry, lending the name City Lights to Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s infamous San Francisco bookstore and publisher. And it seems he also maybe had some small effect on physics, or on the most famous of physicists, who might have harbored a secret ambition to be a silent film comedian—or to communicate, at least, with the universal effectiveness of one as skilled as Charlie Chaplin, favorite of geniuses and grandmothers (and genius grandmothers) everywhere.

Related Content:

60+ Free Charlie Chaplin Films Online

Hear Albert Einstein Read “The Common Language of Science” (1941)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Love this exchange

Einstein: “What I most admire about your art, is your universality. You don’t say a word, yet the world understands you!”

Chaplin: “True. But your glory is even greater! The whole world admires you, even though they don’t understand a word of what you say.”

“If you can’t explain something in simple terms, you have not understood it”. This quote attributed to Richard Feynman means more or less the same, without the wit of Chaplin/Einstein. What was important about Feynman is that he applied this principle in all his writings and teachings with an almost 100% of success.

What surprises me, though, is that people insist on ignoring one of his main starting points: science must disregard the concept of intellectual or academic “authority”, since authorities will always be proven wrong; so this is nice, wit and instructive because of what is said, not by whom.