Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring premiered in 1913, and its violent break from musical and choreographic tradition, so the story goes, pushed the genteel Parisian audience to violent rebellion. That tale may have grown taller over the past century, but public distaste for then-novel trends in all forms of “modern art” has left a paper trail. Here we have a particularly amusing exhibit, and long an obscure one: The Cubies’ ABC, a picture book by a couple named Mary Mills and Earl Harvey Lyall. They were inspired by another major cultural event of 1913, the International Exhibition of Modern Art, or “Armory Show,” which offered the United States of America its first look at groundbreaking work by Marcel Duchamp, Pablo Picasso, and Wassily Kandinsky, among a host of other foreign artists.

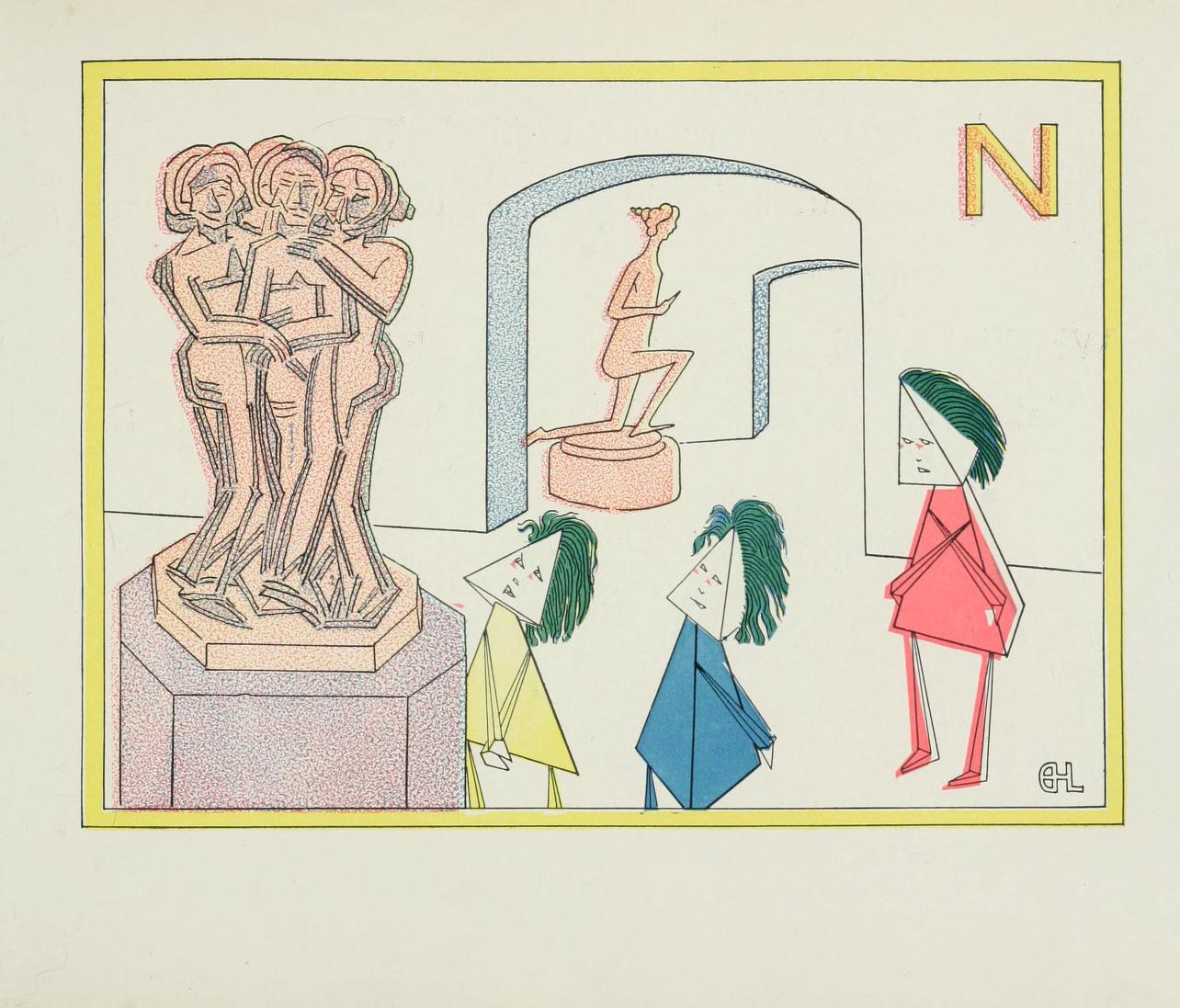

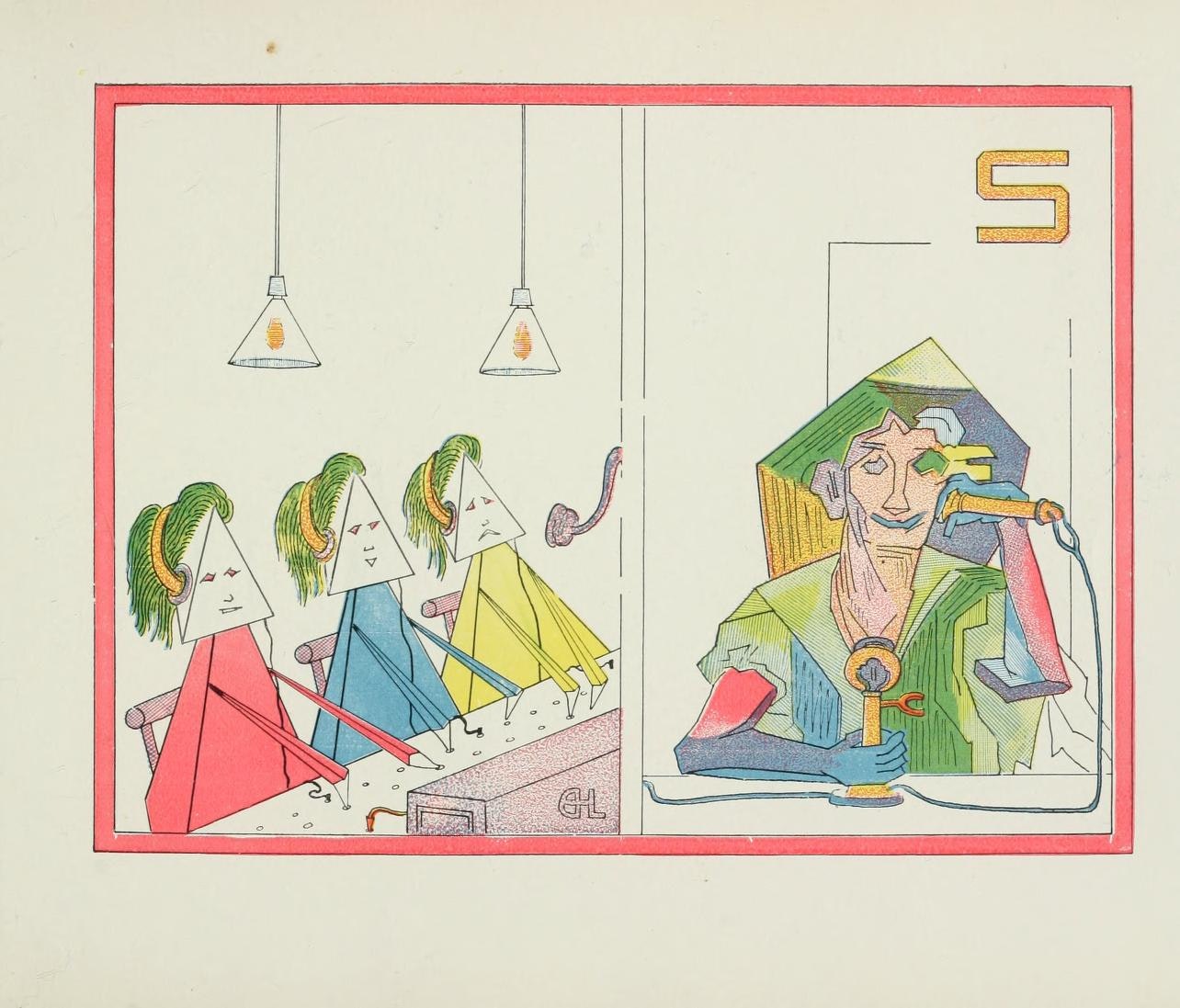

The Lyalls, evidently, were not impressed. In order to ridicule what they seem to have considered the pretensions of the avant-garde, they came up with the Cubies, a trio of angular, wild-haired troublemakers bent on discarding all established conventions in the name of Ego, the Future, and Intuition.

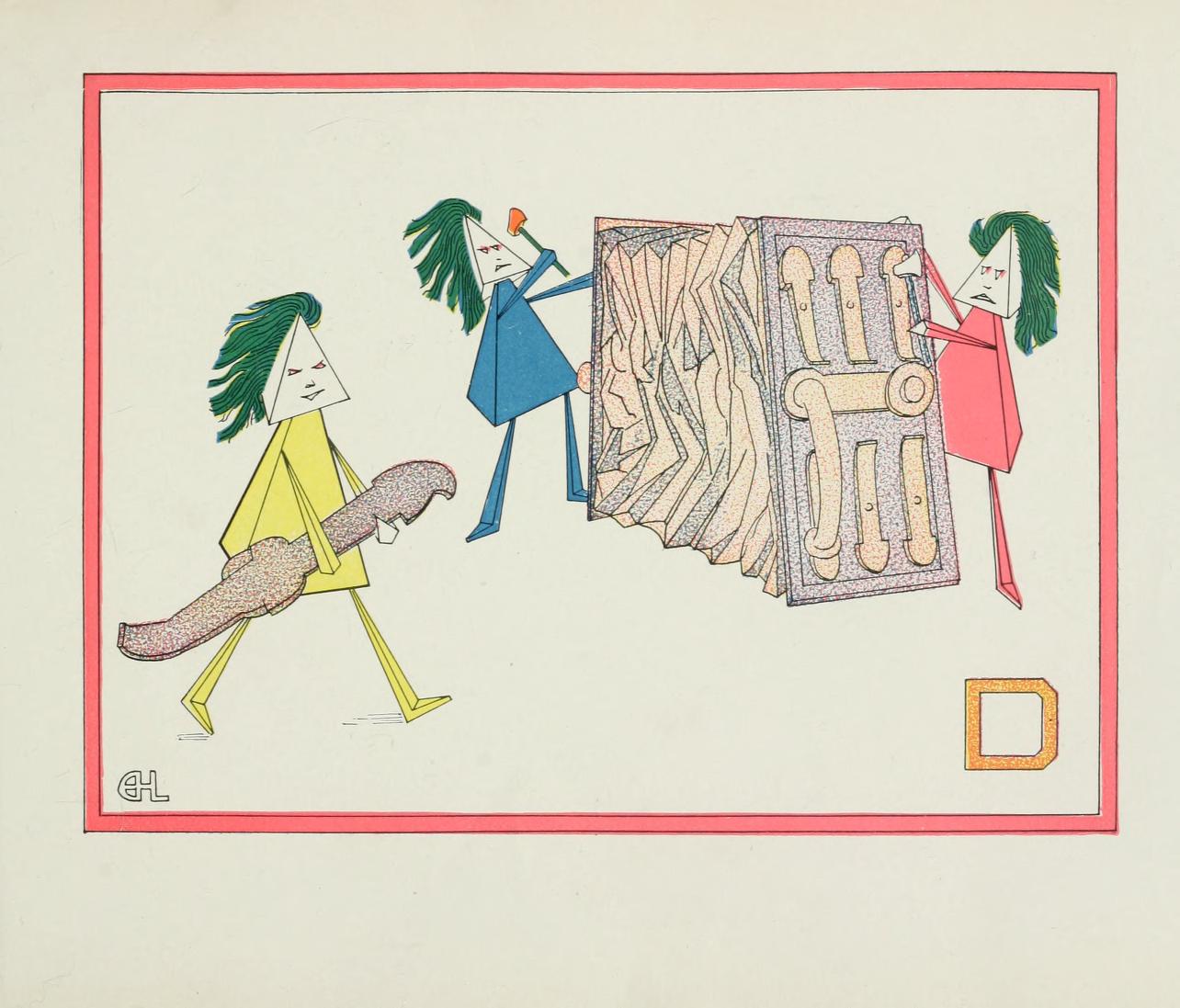

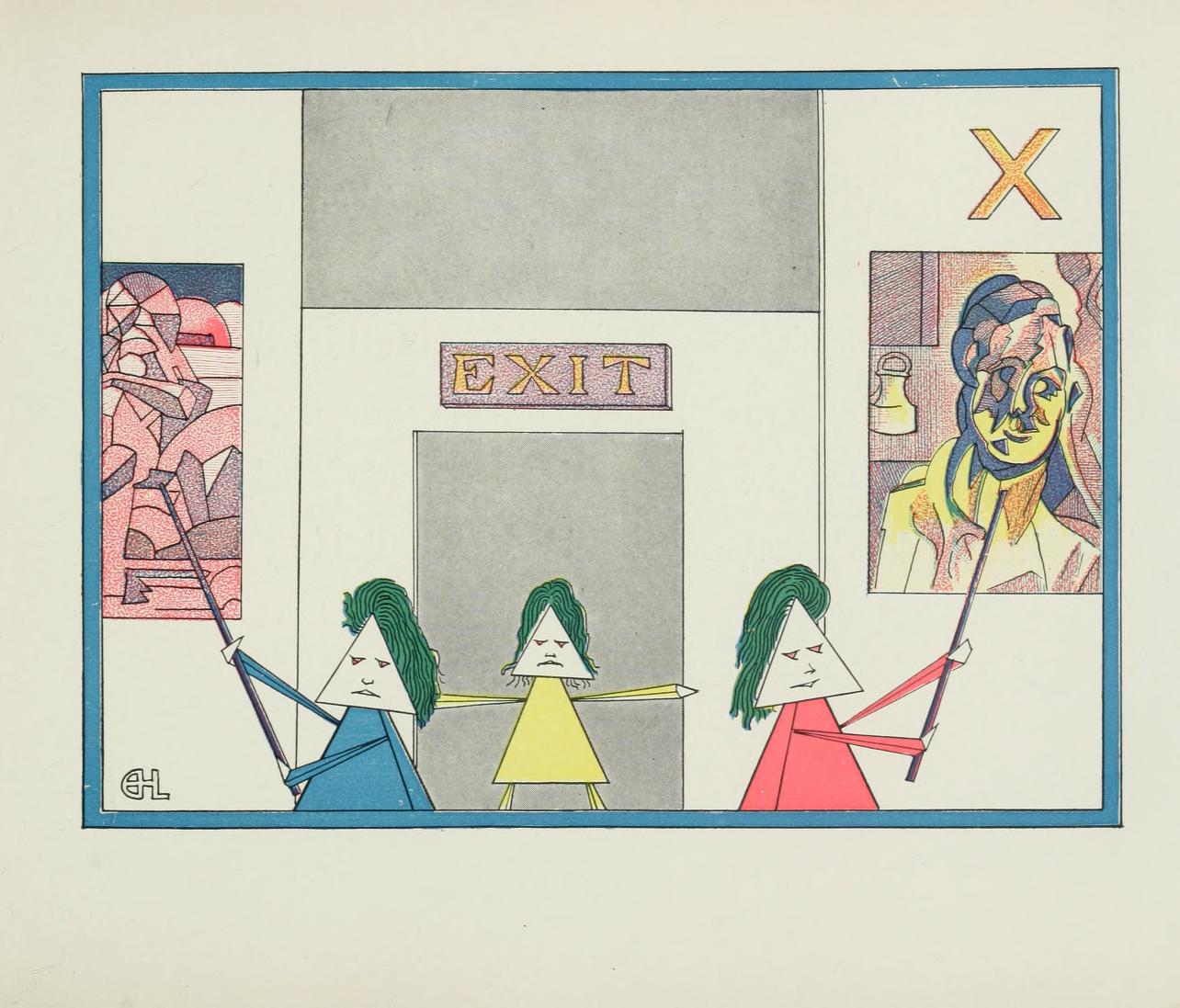

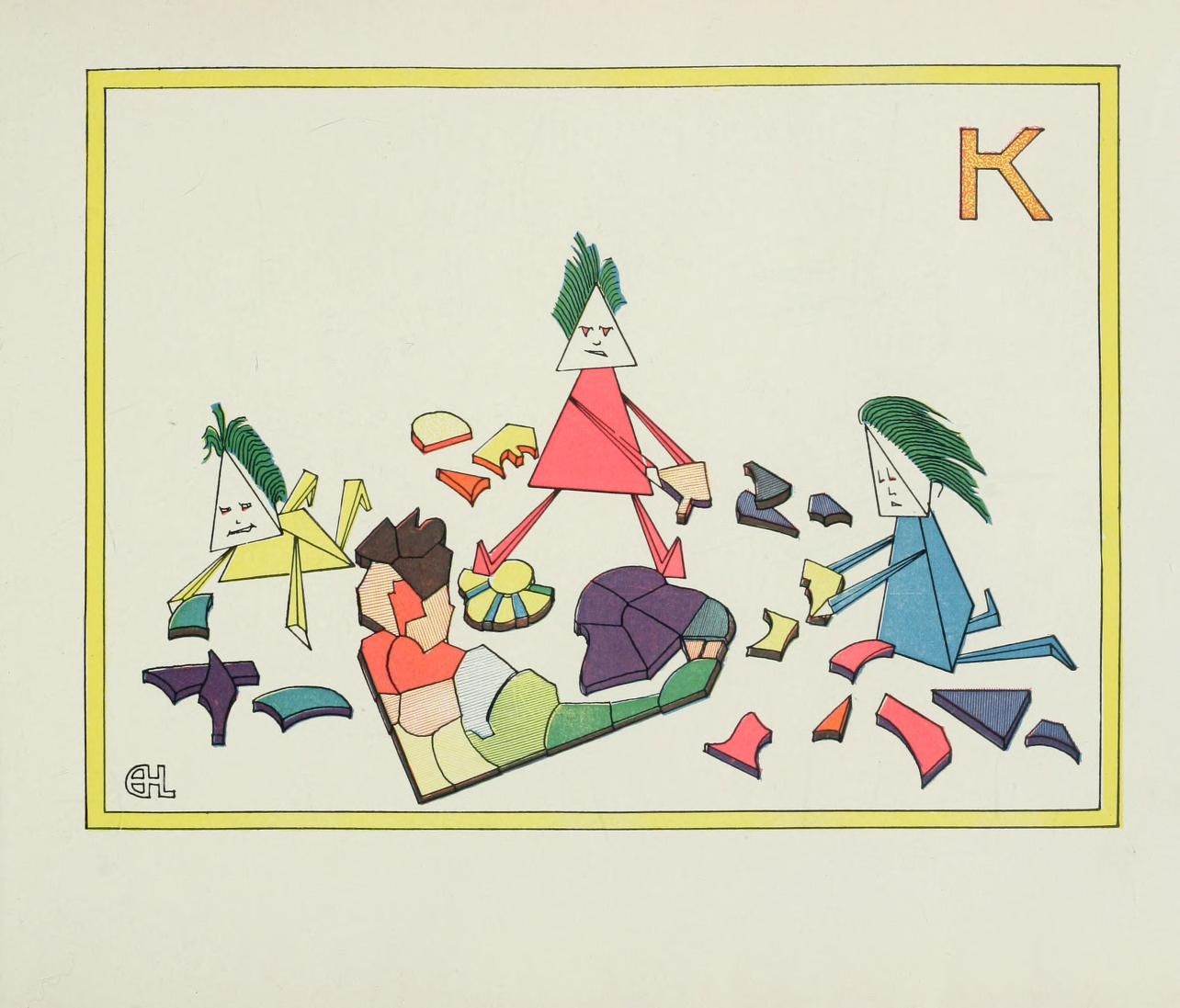

Those three concepts get their own pages in this alphabetically organized book, as do artists — not that the authors would unironically grant them the title — like Duchamp, “the Deep-Dyed Deceiver, who, drawing accordions, labels them stairs”; Kandinsky, painter of “Kute ‘improvisations’ ”; and even Gertrude Stein, “eloquent scribe of the Futurist soul.” X stands, of course, for “the Xit,” a direction “Xtremely alluring when Cubies invite us to study their Art.”

“We tend to forget, now that the Cubists and Futurists have become as integral to the history of art as the painters of the Dutch Golden Age and the Italian Renaissance, how hostile most people — even most artists — felt toward the non-representational innovations of the artists on display at the Armory,” says the Public Domain Review, where you can read The Cubies’ ABC in full.

You can also buy a copy of the reprint organized by gallerist Francis Naumann in commemoration of the Armory show’s centenary. “People in those days thought that they could stop modern art in its tracks,” says Naumann in a New Yorker piece on the book. Did the Lyalls think the Cubies’ antics would land a decisive blow against abstraction and subjectivity? Then again, could they have imagined us enjoying them more than a hundred years later, in a time unknowable to even the most far-sighted Futurist?

Related Content:

Take a Virtual Tour of the 1913 Exhibition That Introduced Avant-Garde Art to America

The Nazi’s Philistine Grudge Against Abstract Art and The “Degenerate Art Exhibition” of 1937

The Guggenheim Puts Online 1700 Great Works of Modern Art from 625 Artists

The Anti-Slavery Alphabet: 1846 Book Teaches Kids the ABCs of Slavery’s Evils

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry’s standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.

So this was not only in 1913. Even now modern artists paint absolute nonsense, but for some reason it is considered art. How? Why? When you read life stories of ordinary people, it is much more interesting. And here the “artist” simply moved from side to side across the canvas, and sold it for millions of dollars. I used to draw this on wallpaper when I was a kid.