In 1919, Sigmund Freud published “The ‘Uncanny,’” his rare attempt as a psychoanalyst “to investigate the subject of aesthetics.” The essay arrived in the midst of a modernist revolution Freud himself unwittingly inspired in the work of Surrealists like Salvador Dali, Andre Breton, and many others. He also had an influence on another artist of the period: his niece Martha-Gertrud Freud, who started going by the name “Tom” after the age of 15, and who became known as children’s book author and illustrator Tom Seidmann-Freud after she married Jakob Seidmann and the two established their own publishing house in 1921.

Seidmann-Freud’s work cannot help but remind students of her uncle’s work of the unheimlich—that which is both frightening and familiar at once. Uncanniness is a feeling of traumatic dislocation: something is where it does not belong and yet it seems to have always been there. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the Seidmann-Freud’s named their publishing company Peregrin, which comes from “the Latin, Peregrinos,” notes an exhibition catalogue, “meaning ‘foreigner,’ or ‘from abroad’—a title used during the Roman Empire to identify individuals who were not Roman citizens.”

Uncanny dislocation was a theme explored by many an artist—many of them Jewish—who would later be labeled “decadent” by the Nazis and killed or forced into exile. Seidmann-Freud herself had migrated often in her young life, from Vienna to London, where she studied art, then to Munich to finish her studies, and finally to Berlin with her husband. She became familiar with the Jewish philosopher and mystic Gershom Scholem, who interested her in illustrating a Hebrew alphabet book. The project fell through, but she continued to write and publish her own children’s books in Hebrew.

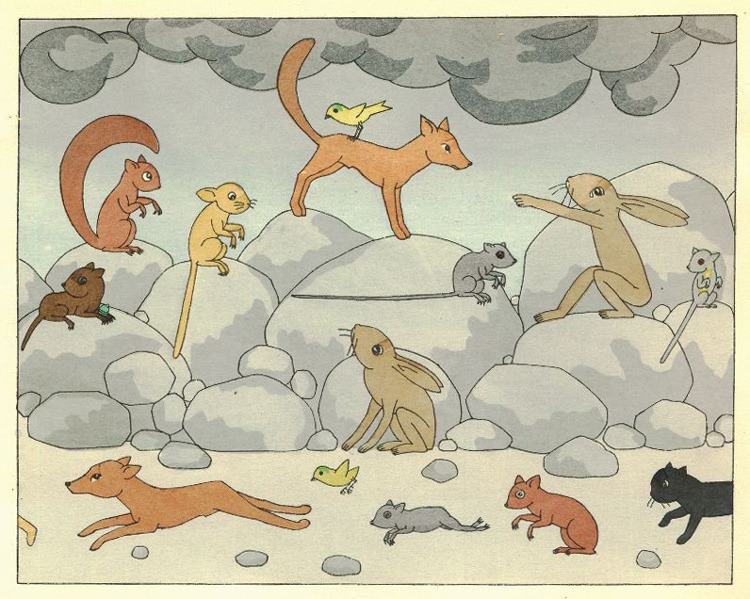

In Berlin, the couple established themselves in the Charlottenburg neighborhood, the center of the Hebrew publishing industry. Seidmann-Freud’s books were part of a larger effort to establish a specifically Jewish modernism. Tom “was a typical example of the busy dawn of the 1920s,” Christine Brinck writes at Der Tagesspiegel. Scholem called the chain-smoking artist an “authentic Bohèmienne” and an “illustrator… bordering on genius.” Her work shows evidence of a “close familiarity with the world of dreams and the subconscious,” writes Hadar Ben-Yehuda, and a fascination with the fear and wonder of childhood.

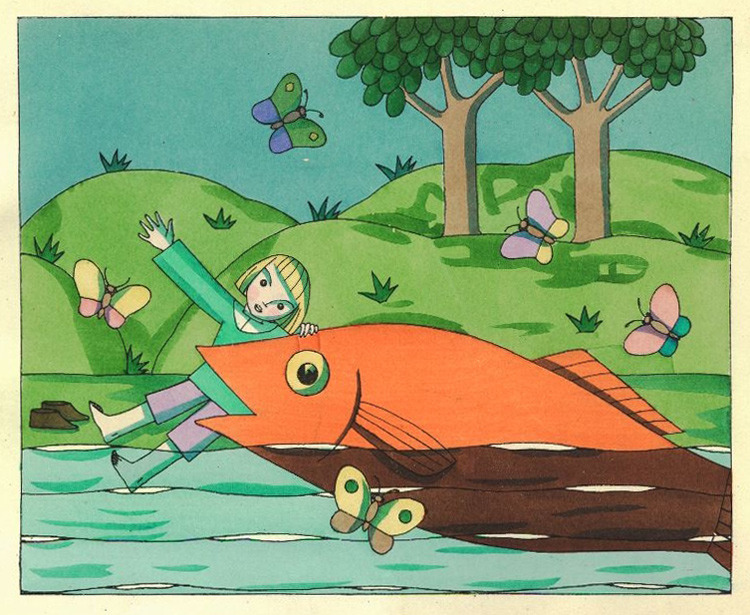

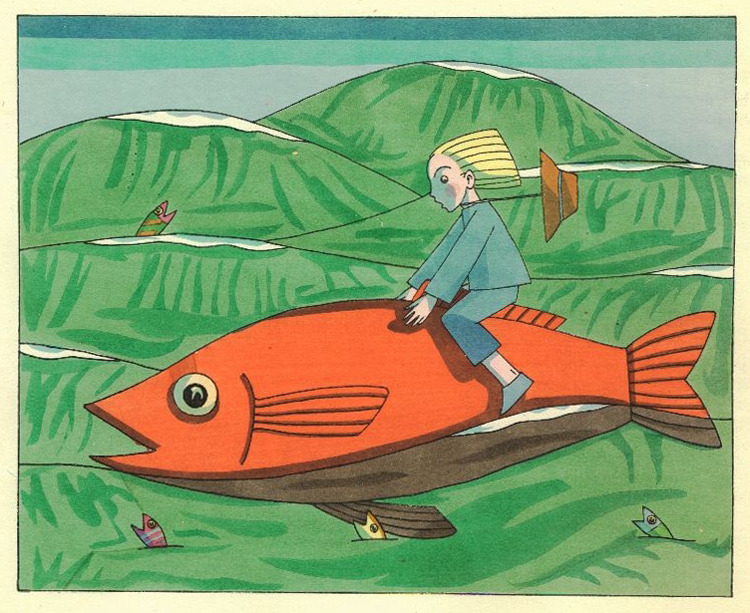

In her 1923 The Fish’s Journey, Seidmann-Freud draws on a personal trauma, “the first real tragedy to have struck her young life when her beloved brother Theodor died by drowning.” Other works illustrate texts—chosen by Jakob and the couple’s business partner, poet Hayim Nahman Bialik—by Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm, “with drawings adapted to the landscapes of a Mediterranean community,” “a Jewish, socialist notion… added to the texts,” “and the difference between boys and girls made indecipherable,” the Seidmann-Freud exhibition catalogue points out.

These books were part of a larger mission to “introduce Hebrew-speaking children to world literature, as part of establishing a modern Hebrew society in Palestine.” Tragically, the publishing venture failed, and Jakob hung himself, the event that precipitated Tom’s own tragic end, as Ben-Yehuda tells it:

The delicate, sensitive illustrator never recovered from her husband’s death. She fell into depression and stopped eating. She was hospitalized, but no one from her family and friends, not even her uncle Sigmund Freud who came to visit and to care for her was able to lift her spirits. After a few months, she died of anorexia at the age of thirty-eight.

Seidmann-Freud passed away in 1930, “the same year that the liberal democracy in Germany, the Weimar Republic, started it frenzied downward descent,” a biography written by her family points out. Her work was burned by the Nazis, but copies of her books survived in the hands of the couple’s only daughter, Angela, who changed her name to Aviva and “emigrated to Israel just before the outbreak of World War II.”

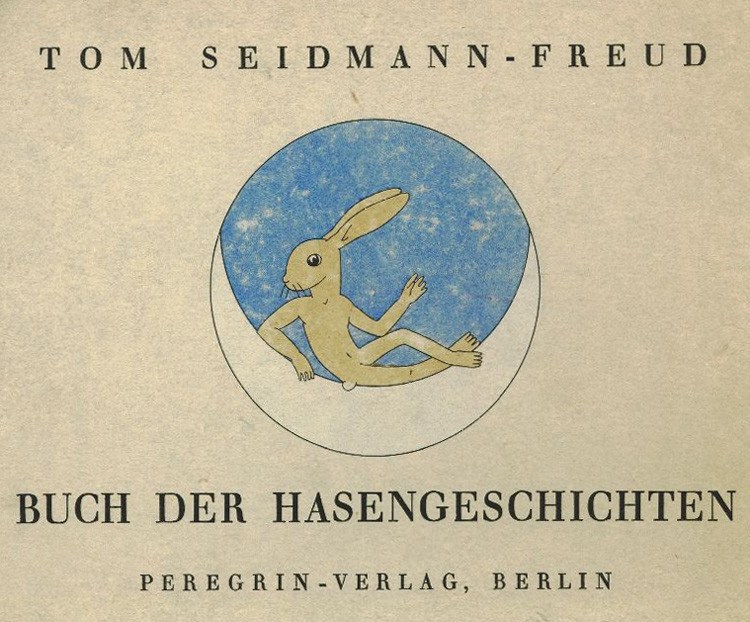

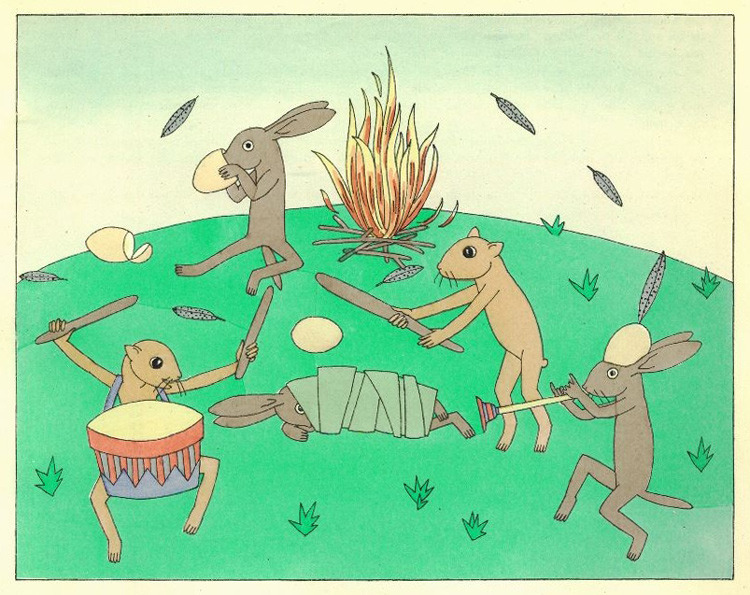

The “whimsically apocalyptic” illustrations in books like Buch Der Hasengeschichten, or The Book of Rabbit Stories from 1924, may seem more ominous in hindsight. But we can also say that Tom, like her uncle and like so many contemporary avant-garde artists, drew from a general sense of uncanniness that permeated the 1920s and often seemed to anticipate more full-blown horror. See more Seidmann-Freud illustrations at 50 Watts, the Freud Museum London, KulturPort, and at her family-maintained site, where you can also purchase prints of her many weird and wonderful scenes.

via 50 Watts

Related Content:

Sigmund Freud Speaks: Hear the Only Known Recording of His Voice, 1938

Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

If Aviva emigrated before the outbreak of WWII, it wasn’t to Israel that she was immigrating.