Buckminster Fuller had a difficult time as an inventor in his early years. “Having been expelled from Harvard for irresponsible conduct,” notes The Guardian, “he struggled to find a job and provide a living for his young family in his early 30s.” Despite later successes, and a later reputation as legendary as Nikola Tesla’s, he was often, like Tesla, seen by critics as a utopian visionary, whose visions were too impractical to really change the world.

But his body of work remains a testament to an imagination that rises above the trends of industrial design and engineering. After a period of decline, for example, Fuller’s geodesic domes experienced a revival in the early 2000’s when “aging baby-boomers across America” began “building dream homes in the shape of geodesic domes.” Meanwhile in Cornwall, England, a few years ahead of the curve, Dutch-born businessman and archaeologist-turned-successful-music-producer Sir Timothy Smit broke ground on what would become a far more British use of Fullerist principles.

In the late 90s, Smit started work on an enormous complex of geodesic biomes called the Eden Project, a facility “akin to a quintessentially Victorian creation: the English greenhouse,” which reached its apex in the famed “Crystal Palace” built for the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851. These were buildings “born out of a playful, decadent imagination—yet in their architecture and design they often opened new pathways for the future.” So too do Fuller’s designs, in an application melding Victorian and Fullerist ideas about curatorship and sustainability.

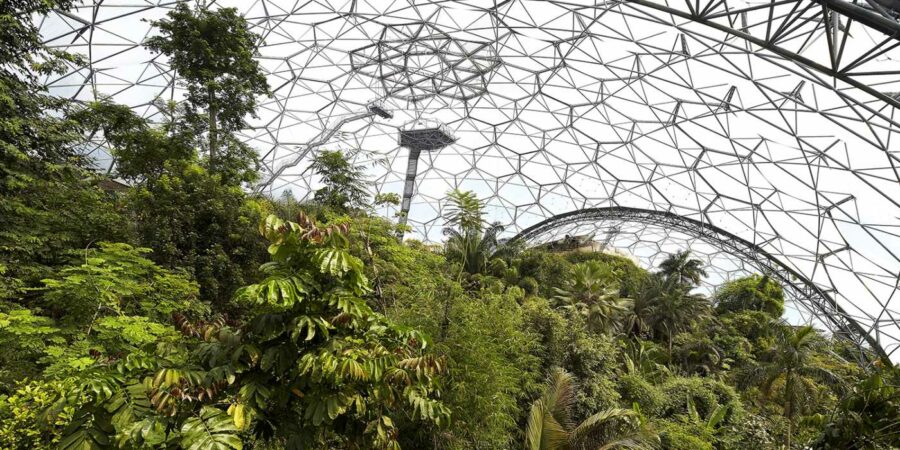

Looking like “clusters of soap bubbles” the Eden Project slowly rose above an exhausted clay pit and opened in 2001 (see a short time-lapse film of the construction above). Each of the two huge central domes recreates an ecosystem. The Rainforest Biome allows visitors to get lost in nearly 4 acres of tropical forest and includes banana, coffee, and rubber plants. The Mediterranean Biome houses an acre and a half of olives and grape vines. Smaller adjoining domes house thousands of additional plant species. There is a performance space and a yearly music festival; sculptures and art exhibitions in both the indoor and outdoor gardens. The facility has hosted well over a million visitors each year.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

In 2016, the Eden Project began planting redwoods, introducing a forest of the North American trees to Europe for the first time. Next year, it will begin drilling for a geothermal energy project to turn heat from the granite underground into power, an undertaking that, unlike fracking, will not release contaminants into the water supply or additional fossil fuels into the air and could power and heat the facility and 5000 additional homes. In 2018, the project began construction on Eden Project North, in Morecambe, Lancashire, with buildings designed to look like giant mussels and a focus on marine environments.

Eden Project International aims to build unique facilities all around the world, “to create new attractions with a message of environmental, social and economic regeneration” and “to protect and rejuvenate natural landscapes.” None of these ambitious expansions use the geodesic domes of the original Eden Project, but that is not a reflection on the domes’ structural soundness. Many other transparent uses of Fuller’s design have encountered difficulties with water tightness and heat flow. The Eden Project’s domes use innovative inflatable, triangular panels instead of glass to solve those problems. Fuller surely would have approved.

The project also represents a poignant personal vindication for the Fuller family. Fuller “vowed to dedicate his life to improving standards of living through good design,” The Guardian writes, after his daughter Alexandra died in 1922. In 2009, his only surviving child, Allegra Fuller Snyder, then 82 and Chairwoman of the Buckminster Fuller Institute, visited the Eden Project. “Of all the projects related to my father’s work,” she remarked afterward, “I would say that this is the one I am most aware of as being a powerful, comprehensive project…. My father would have been just thrilled. He would feel that it is a marvellous application of his thinking.”

Learn more about the Eden Project, which reopens December 3, here. And learn how to “create Eden wherever you are” with the project’s free resources for gardeners at home.

Related Content:

Buckminster Fuller’s Map of the World: The Innovation that Revolutionized Map Design (1943)

The Life & Times of Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Dome: A Documentary

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply