Beware of Greeks bearing gifts. We’ve all heard that proverb, but few of us could name its source: the Trojan priest Laocoön, a historical character in the Aeneid. “Do not trust the Horse, Trojans,” Virgil has him say. “Whatever it is, I fear the Greeks even bearing gifts.” He was right to do so, as we all know, though his death came not at the hands of the Greek army let into Troy by the soldiers hidden inside the Horse, but those of the gods. As Virgil has it, an enraged Laocoön threw a spear at the Horse when his compatriots disregarded words of caution, and in response the goddess Minerva sent forth a couple of sea serpents to do him in.

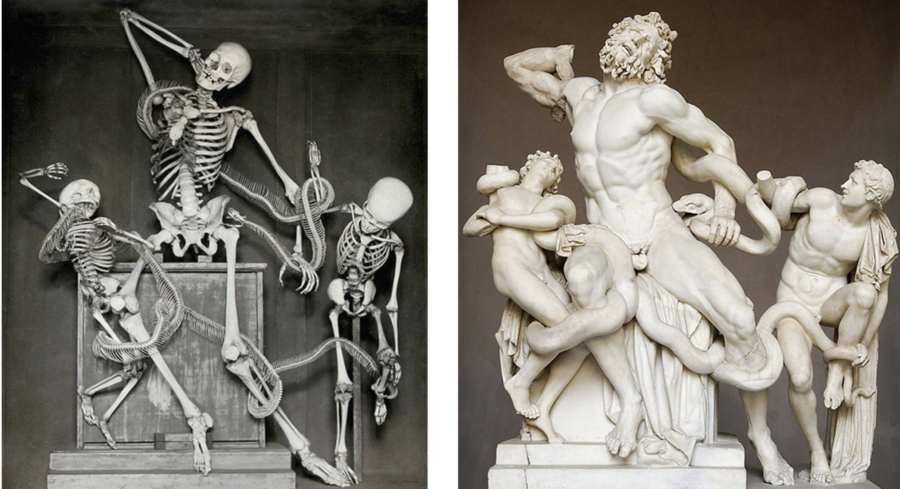

The Aeneid, of course, offers only one account of Laocoön’s fate. Sophocles, for instance, had him spared and only his sons killed, and his ostensible crime — being a priest yet marrying — had nothing to do with the Trojan Horse. But whatever drew the serpents Laocoön’s way, the moment they set upon him and his sons was immortalized by Rhodian sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus in Laocoön and His Sons, among the most famous ancient sculptures in existence since its excavation in 1506. (The sculpture was originally created somewhere between 200 BC and 70 AD.) Various tributes have been paid to it over the centuries, most notably by an Austrian anatomist named Josef Hyrtl, whose built his highly Halloween-suitable recreation out of skeletons — both human and snake.

“According to Christopher Polt, an assistant professor in the classical studies department at Boston College who tweeted a side-by-side comparison of the two versions, Hyrtl created his take on the sculpture at the University of Vienna around 1850,” writes Hyperallergic’s Valentina Di Liscia. In response, a historian named Gregory Stringer tweeted that Hyrtl must have been able to intuit the “proper pose” of Laocoön’s right arm, since in the mid-19th century the sculpture’s original arm was still missing, yet to be rediscovered and reattached, and since 1510 had been replaced in copies with an incorrectly outstretched substitute. Laocoön and His Sons now resides at the Vatican (learn more about it in the Smarthistory video below), but Hyrtl’s skeletal Laocoön and His Sons was destroyed in the 1945 Allied bombing of Vienna.

In 2018, a similar project was attempted again for an exhibit at the Houston Museum of Natural Science. The new all-skeleton version of Laocoön and His Sons was created, as the Houston Press’ Jef Rouner reports, by taxidermist Lawyer Douglas, taxidermy collector Tyler Zottarelle, and artist Joshua Hammond. “It looks a lot like interpretative dance,” Rouner quotes Douglas as saying of Hyrtl’s work. “It’s a beautiful piece, but I was concerned it wasn’t able to capture the original struggle of animal versus human.” Though Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus’ original is known as a “prototypical icon of human agony,” it turns out that “getting perpetually grinning skulls to seem in agony is harder than you might think.” But if any time of the year is right for grinning skulls to express the human experience, surely this is it.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Free Art & Art History Courses

How Ancient Greek Statues Really Looked: Research Reveals Their Bold, Bright Colors and Patterns

An Artist Crochets a Life-Size, Anatomically-Correct Skeleton, Complete with Organs

Celebrate The Day of the Dead with The Classic Skeleton Art of José Guadalupe Posada

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Leave a Reply