“Correlation does not equal causation” isn’t always a fun thing to say at parties, but it is always a good phrase to keep in mind when approaching survey data. Does the study really show that? Might it show the opposite? Does it confirm pre-existing biases or fail to acknowledge valid counterevidence? A little bit of critical thinking can turn away a lot of trouble.

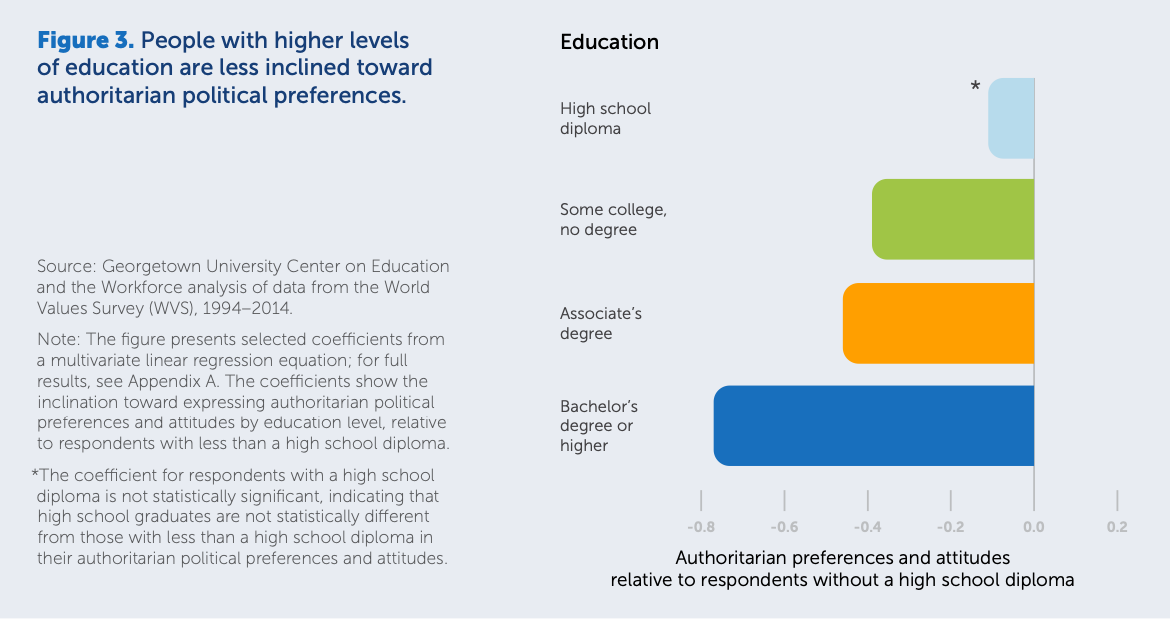

I’ll admit, a new study, “The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes,” confirms many of my own biases, suggesting that higher education, especially the liberal arts, reduces authoritarian attitudes around the world. The claim comes from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, which analyzed and aggregated data from World Values Surveys conducted between 1994 and 2016. The study takes it for granted that rising authoritarianism is not a social good, or at least that it poses a distinct threat to democratic republics, and it aims to show how “higher education can protect democracy.”

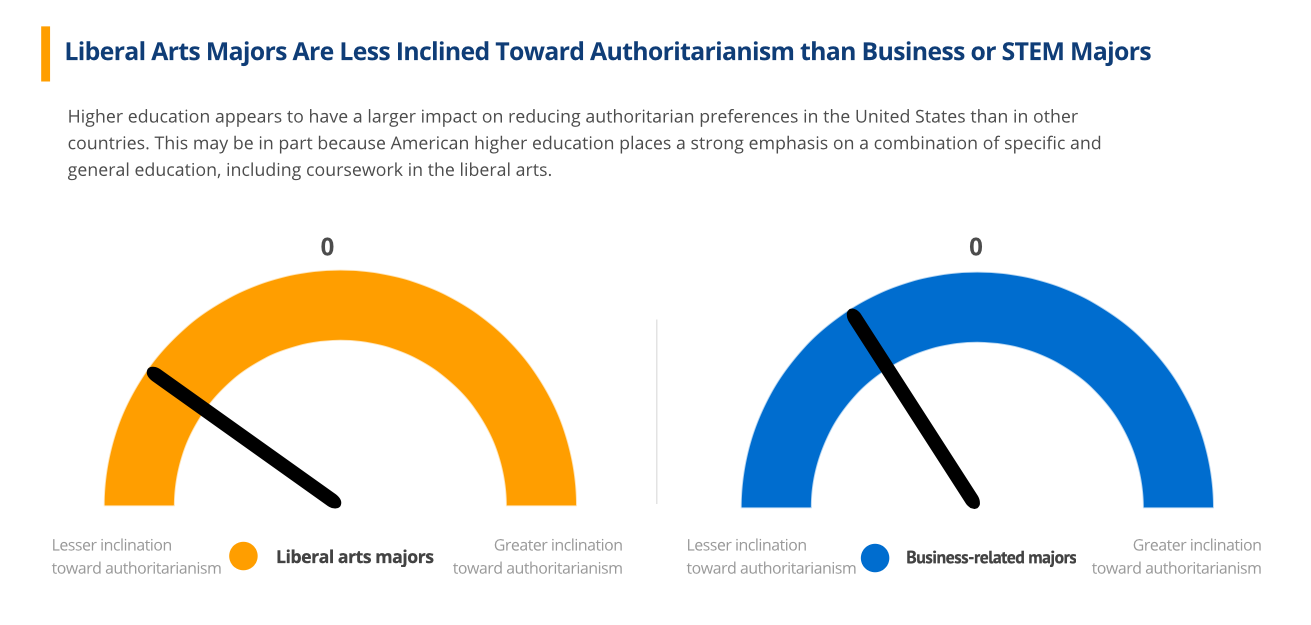

Authoritarianism—defined as enforcing “group conformity and strict allegiance to authority at the expense of personal freedoms”—seems vastly more prevalent among those with only a high school education. “Among college graduates,” Elizabeth Redden writes at Inside Higher Ed, “holders of liberal art degrees are less inclined to express authoritarian attitudes and preferences compared to individuals who hold degrees in business or science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields.”

The “valuable bulwark” of the liberal arts seems more effective in the U.S. than in Europe, perhaps because “American higher education places a strong emphasis on a combination of specific and general education,” the full report speculates. “Such general education includes exposure to the liberal arts.” The U.S. ranks at a moderate level of authoritarianism compared to 51 other countries, on par with Chile and Uruguay, with Germany ranking the least authoritarian and India the most—a 6 on a scale of 0–6.

Higher education also correlates with higher economic status, suggesting to the study authors that economic security reduces authoritarianism, which is expressed in attitudes about parenting and in a “fundamental orientation” toward control over autonomy.

The full report does go into greater depth, but perhaps it raises more questions than it answers, leaving the intellectually curious to work through a dense bibliography of popular and academic sources. There is a significant amount of data and evidence to suggest that studying the liberal arts does help people to imagine other perspectives and to appreciate, rather than fear, different cultures, religions, etc. Liberal arts education encourages critical thinking, reading, and writing, and can equip students with tools they need to distinguish reportage from pure propaganda.

But we might ask whether these findings consistently obtain under actually existing authoritarianism, which “tends to arise under conditions of threat to social norms or personal security.” In the 2016 U.S. election, for example, the candidate espousing openly authoritarian attitudes and preferences, now the current U.S. president, was elected by a majority of voters who were well-educated and economically secure, subsequent research discovered, rather than stereotypically “working class” voters with low levels of education. How do such findings fit with the data Georgetown interprets in their report? Is it possible that those with higher education and social status learn better to hide controlling, intolerant attitudes in mixed company?

Learn more at this report summary page here and read and download the full report as a PDF here.

Related Content:

Why We Need to Teach Kids Philosophy & Safeguard Society from Authoritarian Control

Critical Thinking: A Free Course

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

But what does it teach them about the zoo at the British Museum?

This seems to be a narrow interpretation of“authoritarian”. The other candidate in 2016 wanted to take more money away from people and use it to fund more programs. How is bigger government not, by definition, more authoritarian than less government with fewer regulations? I am not commenting on which approach is right or wrong, just noting the inconsistent definition.

I’m puzzled by both the question and the answer.

I’m puzzled by the relevance of the question, Tom.

I cannot understand the significance of the comment. The fact that a government, particularly an elected government, is being called authoritarian because it promises to do things hardly makes it any sense at all. Governments get elected on the basis of their plans to do good things for the nation and its’ people.

Authoritarian is when a totally unelected government decides to spend money on, say, setting up a secret police organization.