Leonardo da Vinci didn’t really have hobbies; he had passionate, unpaid obsessions that filled whole notebooks with puzzles scientists are still trying to solve. Many of the problems to which he applied himself were those none of his contemporaries understood, because he was the only person to have noticed them at all. The amateur anatomist was the first, for example, “to sketch trabeculae,” notes Medievalists.net, “and their snowflake-like fractal patterns in the 16th century.”

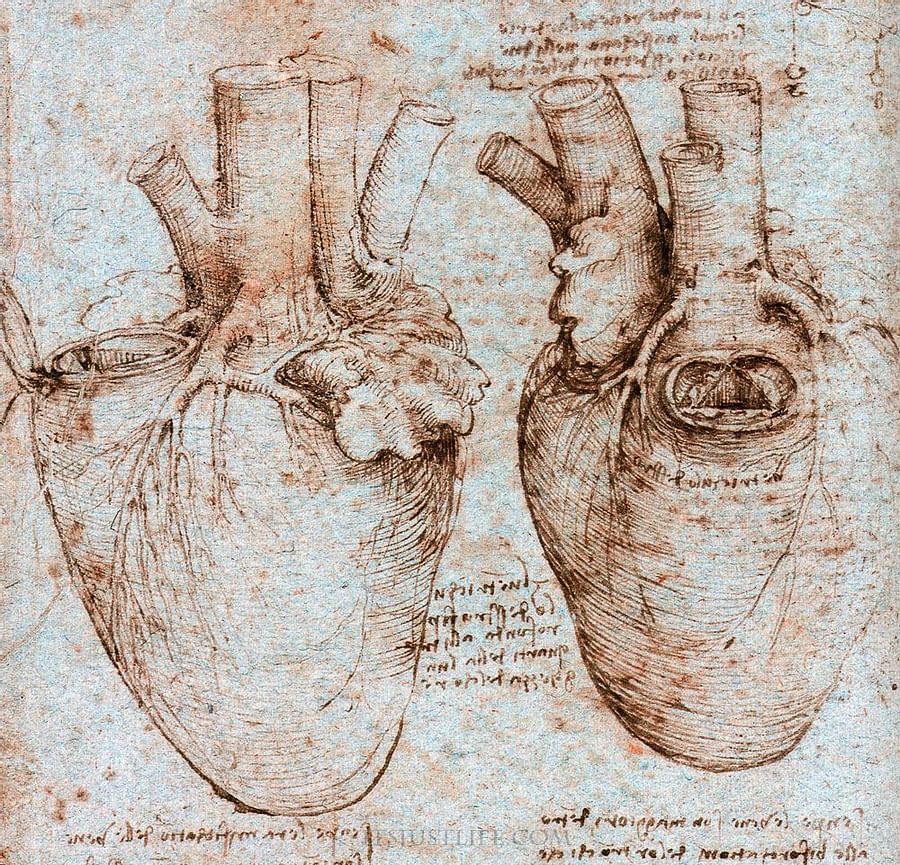

These geometric patterns of muscle fibers on the inner surface of the heart have remained a mystery for over 500 years since Leonardo’s anatomical investigations, carried out first on pig and oxen hearts, then later, in hasty dissections in the winter cold, on human specimens. He speculated they might have warmed the blood, but scientists have recently found they enhance blood flow “just like the dimples on a golf ball reduce air resistance.”

Leonardo may have been wide of the mark in his trabeculae theory, not having access to genetic testing, AI, or MRI. But he was the first to describe coronary artery disease, which would become one of the leading causes of death 500 years later. Many of his medical conclusions have turned out to be startingly correct, in fact. He detailed and elegantly sketched the heart’s anatomy from 1507 until his death in 1519, working out the flow of the blood through the body.

As the Medlife Crisis video above explains, Leonardo’s studies on the heart elegantly brought together his interests in art, anatomy, and engineering. Because of this multi-dimensional approach, he was able to explain a fact about the heart’s operation that even many cardiologists today get wrong, the movement of the aortic valve. In order to visualize the “flow dynamics” of the heart’s machinery, without imaging machinery of his own, he built a glass model, and drew several sketches of what he saw. “Incredibly, it took 450 years to prove him right.”

The mind of this extraordinary figure continues to divulge its secrets, and scholars and doctors across multiple fields continue to engage with his work, in the pages, for example, of the Netherlands Heart Journal. His studies on the heart particularly show how his astonishing breadth of knowledge and skill paradoxically made him such a focused, determined, and creative thinker.

via Medievalists.net

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Wonderful work from DaVinci,I realy salute this great artist a great historian and a great philosopher and scientist,am an artist too and respect people who are able to see the world holographically.