In the past two decades, the Latin American world has seen a tremendous resurgence of indigenous language study and literature. Some Mexican writers are “ditching Spanish,” Dora Ballew writes, for “Zapotec, Tzotzil, Mayan and other languages spoken long before Europeans washed up on the shores of what is now Mexico.” Large anthologies of such literature have been published since 2001. The move is not a recovery of lost languages and cultures, but an affirmation of “the number of people fluent in both an indigenous language and Spanish,” scholars and writers Earl and Sylvia Shorris explain.

“At least several million” indigenous language speakers in Mexico alone ensure that “literature has ample place in which to flourish.” Despite the incursions of both the Aztecs, then the Spanish, speakers of Mixtec, for example, survived and now “inhabit a vast territory of broad mountain ranges and small valleys that stretch across the modern-day states of Puebla, Guerrero and Oaxaca,” writes Dr. Manuel A. Hermann Lejarazu.

An expert on Mixtec codices, Lejarazu ties the contemporary culture of Mixtec speaking people back to the Postclassic past, “a period between the tenth and sixteenth centuries when political centres proliferated, filling the vacuum left after the collapse of large cities established in preceding centuries.”

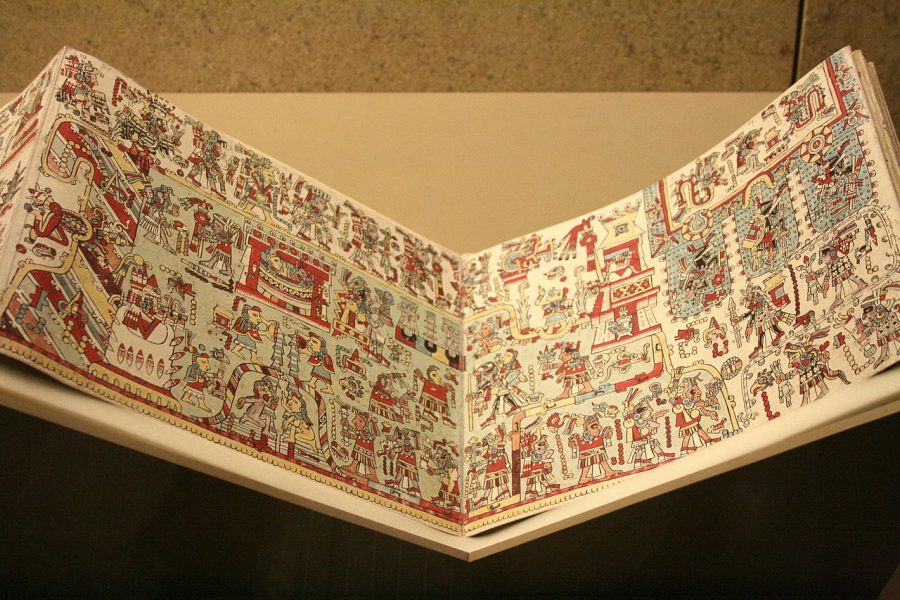

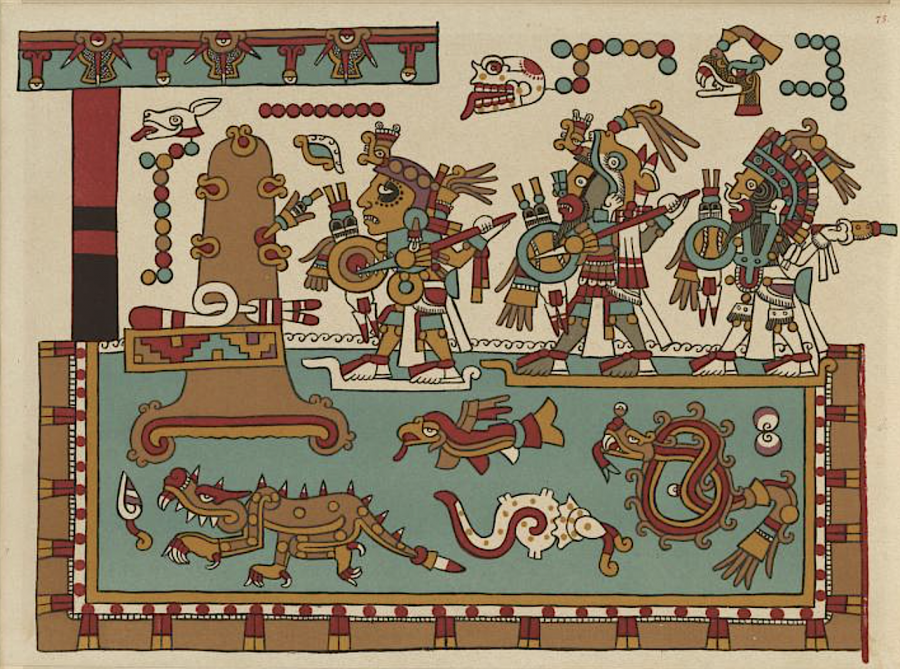

Much of the little that is known of the indigenous Mixtec literary culture comes from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, one of only a handful of pre-Columbian manuscripts in existence. Made of deer skin, the codex “contains two narratives,” the British Museum notes. “One side of the document relates the history of important centres in the Mixtec region, while the other, starting at the opposite end, records the genealogy, marriages and political and military feats of the Mixtec ruler, Eight Deer Jaguar-Claw.”

Although finished around 1556, the pictographic folding manuscript “is considered to be of pre-Hispanic origin,” Lejarazu writes, “since it preserves a strong indigenous tradition in its pictographic techniques, with no demonstrable European influence.” The codex was first discovered in 1854 in a Dominican monastery in Florence. It’s unclear exactly how and when it arrived in Europe, but several such codices “reached the Old World as gifts or as part of the documents submitted to Spanish courts that handled legal matters in the Indies.”

Though severed from its origins, the Codex Zouche-Nuttall is now freely available online in a scanned 1902 facsimile edition at the British Museum and the Internet Archive. You can learn much more about these incredibly rare documents from Lejarazu’s article and Robert Lloyd Williams’ Complete Codex Zouche-Nutall, which explains how the pictographic record functions like a storyboard, or outline, for a complex narrative tradition that tied Mixtec rulers to the gods, to each other, and to the past and future.

Related Content:

Native Lands: An Interactive Map Reveals the Indigenous Lands on Which Modern Nations Were Built

Speaking in Whistles: The Whistled Language of Oaxaca, Mexico

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply