In the 17th and 18th centuries, what we know of as The Age of Enlightenment or early modernity, Europeans traversed the globe and returned to publish travel accounts that cast the natives they encountered as childlike beings, destitute savages, or literal monsters. Unable to make sense of alien languages and cultures, they mistook everything they saw.

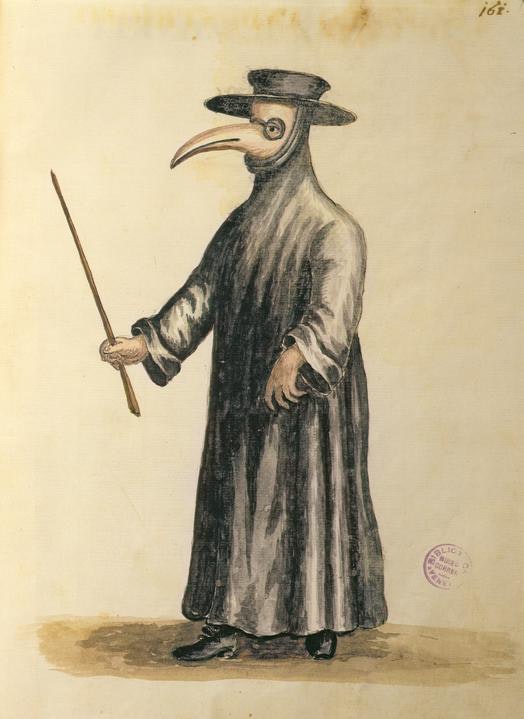

Meanwhile, the bubonic plague swept Europe, and plague doctors wandered towns and countryside in a “fanciful-looking costume [that] typically consisted of a head-to-toe leather or wax-canvas garment,” writes the Public Domain Review, “large crystal glasses; and a long snout or bird beak, containing aromatic spices (such as camphor, mint, cloves, and myrrh), dried flowers (such as roses or carnations), or a vinegar sponge.”

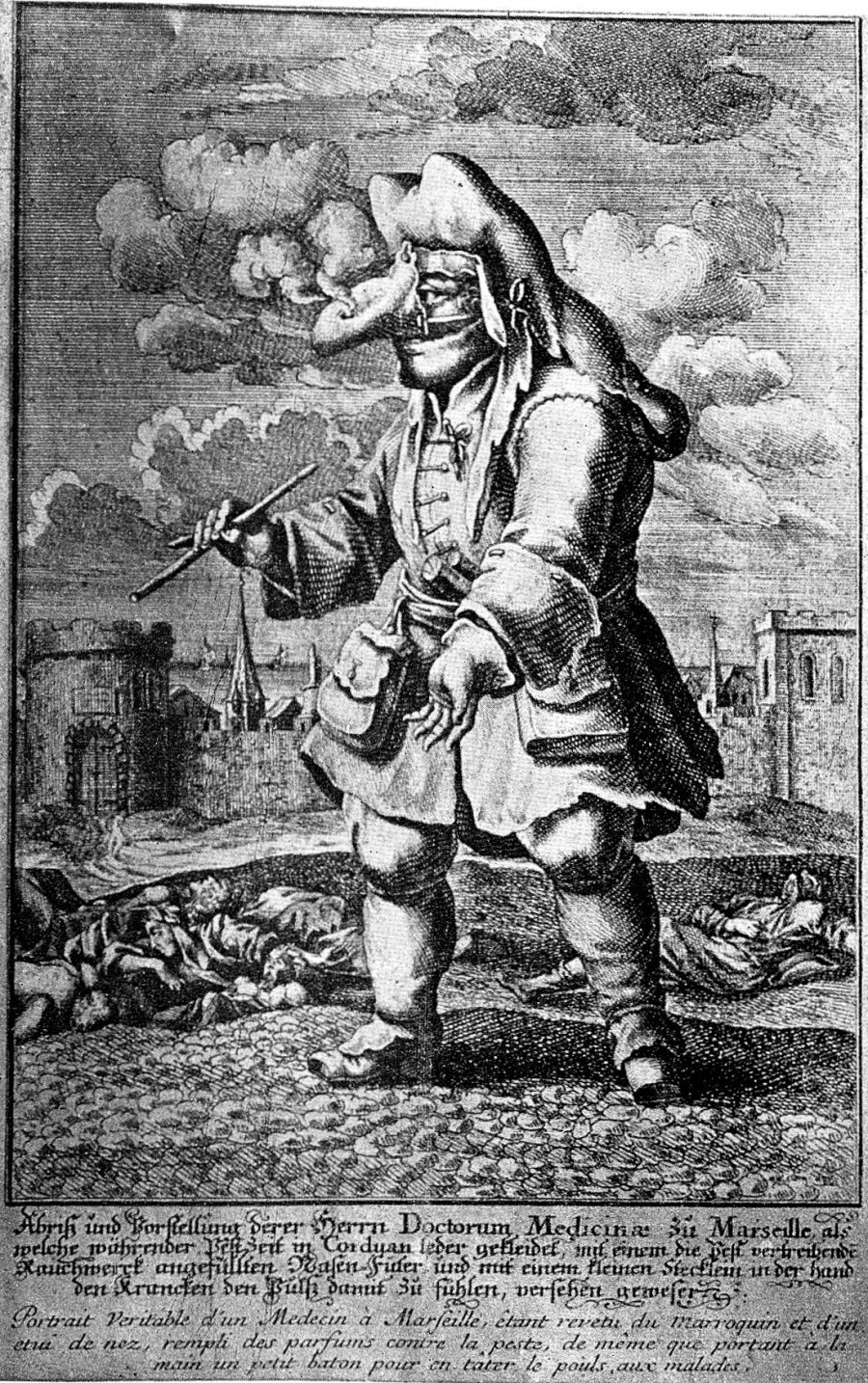

Moreover, the plague doctor—as you can see from illustrations of this bizarre character—also carried with him a wand, “with which to issue instructions,” one scholar writes, “such as ordering disease-stricken houses filled with spiders or toads ‘to absorb the air’ and commanding the infected to inhale ‘bottled wind’ or take urine baths, purgatives, or stimulants.” The wand was also used to forcefully fend off patients.

Visiting travelers from elsewhere might be justified in thinking the plague doctor represented some strange, primitive religious custom: perhaps a monstrous—and mostly ineffective—exorcism ritual. The “early-modern hazmat suit” is perfectly reasonable, of course, if you understand the reigning theory of “miasmas,” which posited that disease is spread through “bad air.” Not entirely wrong, as our current masked existences show, but in the case of the plague, miasma theory was only very partially explanatory.

Which is to say the costume wasn’t entirely useless. “The ankle-length gown and herb-filled beak… would also have offered some protection against germs,” especially since its herbs were sometimes lit on fire and allowed to smolder, sending billowing smoke from the plague doctor’s face. (The satirical engraving above from 1700 mocks this practice.) “The appearance of one of these human-sized birds on a doorstep could only mean that death was near.”

This particular design has been credited to a French doctor, Charles de Lorme, said to have invented it in 1619. “De Lorme thought the beak shape of the mask would give the air sufficient time to be suffused by the protective herbs before it hit the plague doctors’ nostrils and lungs.” Often mistaken for Medieval or Renaissance garb, the plague doctor costume is, in fact, a modern piece of kit.

Much has been made of the bird mask, but as one skeptical history writer has effectively shown, there are good reasons to doubt the widespread adoption of the beak. It may have been a rarity; most plague doctors probably wore what would look to us today like Klan robes and hoods. All the more reason for plague doctor costumes to seem shocking once again, as a British teen discovered when he decided in May to dress the part of the classic beaked figure. (Residents found it “terrifying” and police offered stern “words of advice.”)

No matter how widespread the beak was historically, its iconic status as part of the plague doctor costume remains inscribed in art and culture. “The look was so iconic in Italy that the ‘plague doctor’ became a staple of Italian commedia dell’arte and carnival celebrations,” Erin Blakemore writes at National Geographic. Given the associations a more authentic costume would evoke, no one seems to be clamoring to replace beaked masks with pointed hoods in representations of plague doctors. The beak also symbolically conveys an important fact about plague doctors: they were not healers—they were mostly witnesses of death.

Few of their remedies had any effect. Rather, on the government’s payroll, plague doctors—often second or third-rate practitioners attempting to build a career—recorded demographic data, witnessed wills, and performed autopsies. They were like weird avian aliens come to observe the customs of a continent’s dying population, appearing in what came to be widely understood as the “costume of death,” as the illustration above puts it. See more representations of the plague doctor costume at the Public Domain Review.

Related Content:

The History of the Plague: Every Major Epidemic in an Animated Map

Download Classic Works of Plague Fiction: From Daniel Defoe & Mary Shelley, to Edgar Allan Poe

Isaac Newton Conceived of His Most Groundbreaking Ideas During the Great Plague of 1665

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply