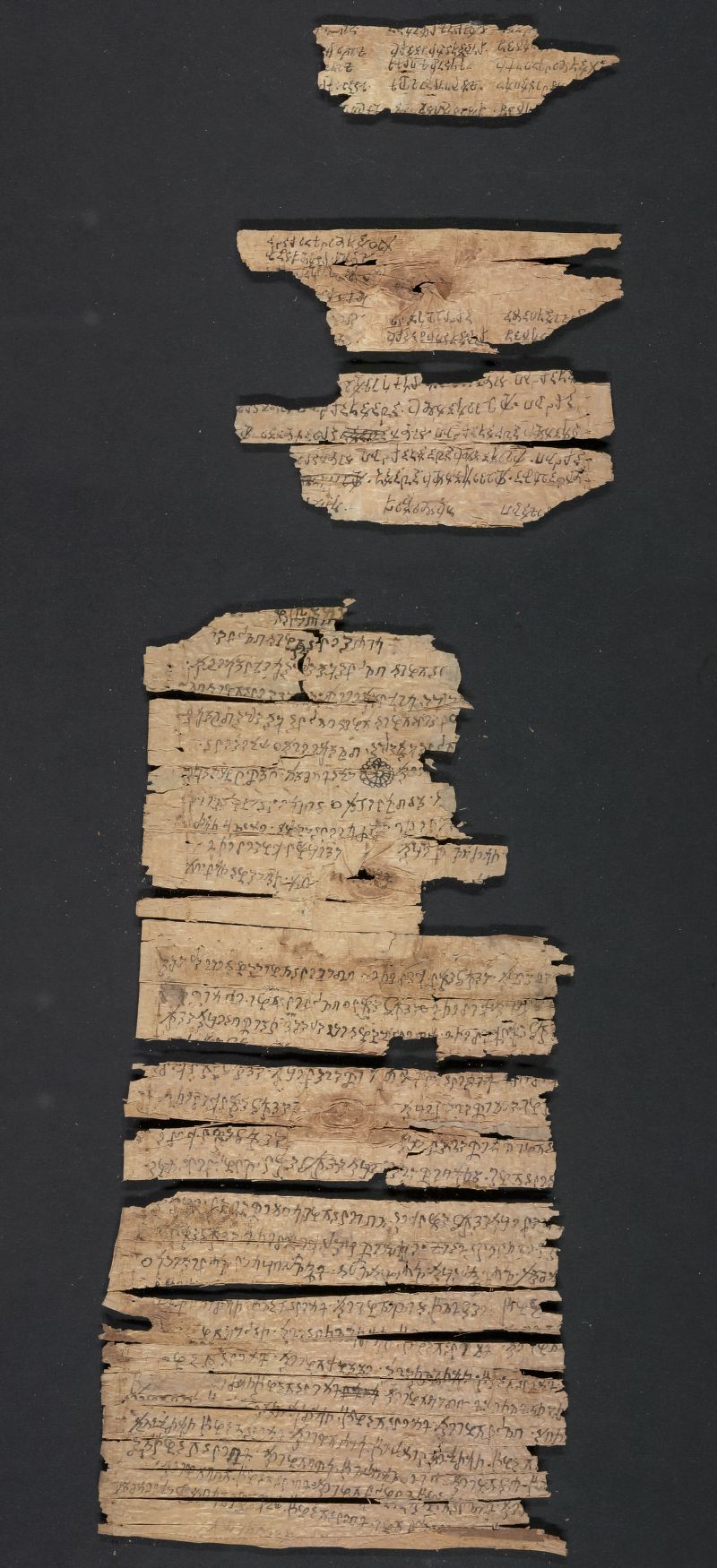

Buddhism goes way back — so far back, in fact, that we’re still examining important evidence of just how far back it goes. Take the exhibit above, which may look like nothing more than a collection of faded scraps with writing on them. In fact, they’re pieces of the laboriously and carefully unrolled and scanned Gandhara Scroll, which, having originally been written about two millennia ago, ranks as one of the oldest Buddhist manuscripts currently known. You can read the scroll’s story at the blog of the Library of Congress, the institution that possesses it and only last year was able to put it online for all to see.

“The scroll originated in Gandhara, an ancient Buddhist kindgom located in what is today the northern border areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan,” writes the Library’s Neely Tucker. “Surviving manuscripts from the Gandharan realm are rare; only a few hundred are known to still exist.” That realm “was under the rule of numerous kings and dynasties, including Alexander the Great, the Mauryan emperor Ashoka and the Kushan emperor Kanishka I,” and for a time “became a major seat of Buddhist art, architecture and learning. One of the region’s most notable characteristics is the Hellenistic style of its Buddhist sculptures, including figures of the Buddha with wavy hair, defined facial features, and contoured robes reminiscent of Greco-Roman deities.”

Written in the Gandhari variant of Sanskrit, the “Bahubuddha Sutra” or “Many Buddhas Sutra,” as this scroll has been called, constitutes part of “the much larger Mahavastu, or ‘Great Story,’ a biography of the Buddha and his past lives.” Here Tucker draws from the scholarship of Richard G. Salomon, emeritus professor of Sanskrit and Buddhist studies at the University of Washington, another institution that holds a piece of the Gandharan Buddhist texts. Many more reside at the British Library, which acquired them in 1994. The Library of Congress bought its Gandhara Scroll from a British dealer more recently, in 2003, and it arrived in what Tucker describes as “an ordinary pen case, accompanied by a handwritten note: ‘Extremely fragile, do not open unless necessary.’ ”

So began “several years of thought and planning to devise a treatment strategy,” an effort that at one point saw the Library’s conservator practicing “her unrolling technique on a dried-up cigar — an item that only approximates the difficulty of working with a compacted birch bark scroll.” Then came “gradual humidification over a few days, careful unrolling by hand with precision tools on a sheet of inert glass, followed by placing another sheet of glass on top once the scroll was completely unrolled,” a “dramatic and silent affair” described in greater detail by Atlas Obscura’s Sabrina Imbler.

The result was six large fragments and more than 100 smaller ones, together constituting roughly 80 percent of the scroll’s original text. You can see all those fragments of the Gandhara Scroll, scanned in high resolution, at the Library of Congress’ web site. This will naturally be a more edifying experience if, like Salomon, you happen to be able to read Gandhari. Even if you can’t, there’s something to be felt in the experience of simply beholding a 2,000 year old text composed on birch bark through the digital medium on which we do most of our reading here in the 21st century — where interest in Buddhism shows no signs of waning.

Related Content:

Breathtakingly-Detailed Tibetan Book Printed 40 Years Before the Gutenberg Bible

The World’s Largest Collection of Tibetan Buddhist Literature Now Online

Google Digitizes Ancient Copies of the Ten Commandments and Genesis

Google Puts The Dead Sea Scrolls Online (in Super High Resolution)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Leave a Reply