Image via Wikimedia Commons

Fifteen centuries after its fall, the Roman Empire lives on in unexpected places. Take, for instance, the former colonial city of Timgad, located in Algeria 300 miles from the capital. Founded by the Emperor Trajan around 100 AD as Colonia Marciana Ulpia Traiana Thamugadi, it thrived as a piece of Rome in north Africa before turning Christian in the third century and into a center of the Donatist sect in the fourth. The three centuries after that saw a sacking by Vandals, a reoccupation by Christians, and another sacking by Berbers. Abandoned and covered by sand from the Sahara from the seventh century on, Timgad was rediscovered by Scottish explorer James Bruce in 1765. But not until the 1880s, under French rule, did a proper excavation begin.

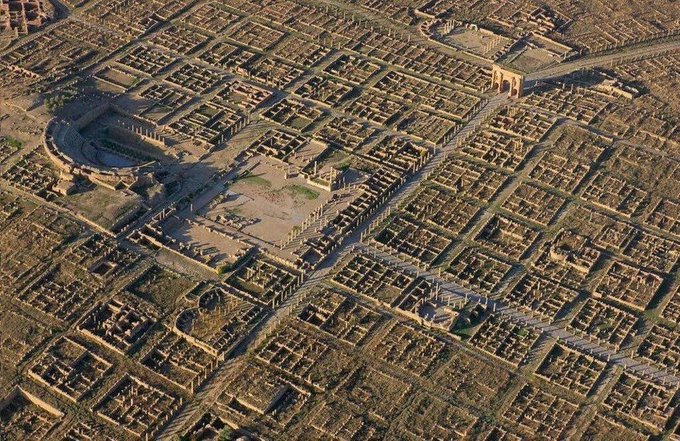

Today a visitor to the ruins of Timgad can see the outlines of exactly where each of its buildings once stood (especially if they have the aerial view of the photo above, recently tweeted out by Architecture Hub). This, in part, is what qualified the place for inscription on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

“With its square enclosure and orthogonal design based on the cardo and decumanus, the two perpendicular routes running through the city, it is an excellent example of Roman town planning,” says UNESCO’s web site. Its “remarkable grid system” — quite normal to 21st-century city-dwellers, much less so in second-century Africa — makes it “a typical example of an urban model” that “continues to bear witness to the building inventiveness of the military engineers of the Roman civilization, today disappeared.”

“Within a few generations of its birth,” writes Messy Nessy,” the outpost had expanded to over 10,000 residents of both Roman, African, as well as Berber descent. “The extension of Roman citizenship to non-Romans was a carefully planned strategy of the Empire,” she adds. “In return for their loyalty, local elites were given a stake in the great and powerful Empire, benefitted from its protection and legal system, not to mention, its modern urban amenities such as Roman bath houses, theatres, and a fancy public library.”

Timgad’s library, which “would have housed manuscripts relating to religion, military history and good governance,” seems to have been fancy indeed, and its ruins indicate the purchase Roman culture managed to attain in this far-flung settlement.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Timgad’s library is just one element of what UNESCO calls its “rich architectural inventory comprising numerous and diversified typologies, relating to the different historical stages of its construction: the defensive system, buildings for the public conveniences and spectacles, and a religious complex.” Having outgrown its original street grid, Timgad “spread beyond the perimeters of its ramparts and several major public buildings are built in the new quarters: Capitolium, temples, markets and baths,” most of which date from the city’s “Golden Age” in the Severan period between 193 and 235.

Image Alan and Flora Botting via Flickr Commons

This makes for an African equivalent of Pompeii, the Roman city famously buried and thus preserved in the explosion of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79. But it is lesser-known Timgad, with its still clearly laid-out blocks, its recognizable public facilities, and its demarcated “downtown” and “suburbs,” that will feel more familiar to us today, whichever city in the world we come from.

via Architecture Hub/MessyNessy

Related Content:

Visit Pompeii (also Stonehenge & Versailles) with Google Street View

Rome Reborn: Take a Virtual Tour Through Ancient Rome, 320 C.E.

Pierre Bourdieu’s Photographs of Wartime Algeria

Replica of an Algerian City, Made of Couscous: Now on Display at The Guggenheim

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Leave a Reply