Image via Wikimedia Commons

Of all the desserts to attain cultural relevance over the past century, can any hope to touch Alice B. Toklas’ famous hashish fudge? Calling for such ingredients as black peppercorns, shelled almonds, dried figs, and most vital of all Cannabis sativa, the recipe first appeared in 1954’s The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book. (Toklas would read the recipe aloud on the radio in the early 1960s, a time when the fudge’s key ingredient had become an object of much more intense public interest.) More than a how-to on Toklas’ favorite dishes, the book is also a kind of memoir, including recollections of her life with Gertrude Stein — herself the author of the ostensible Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.

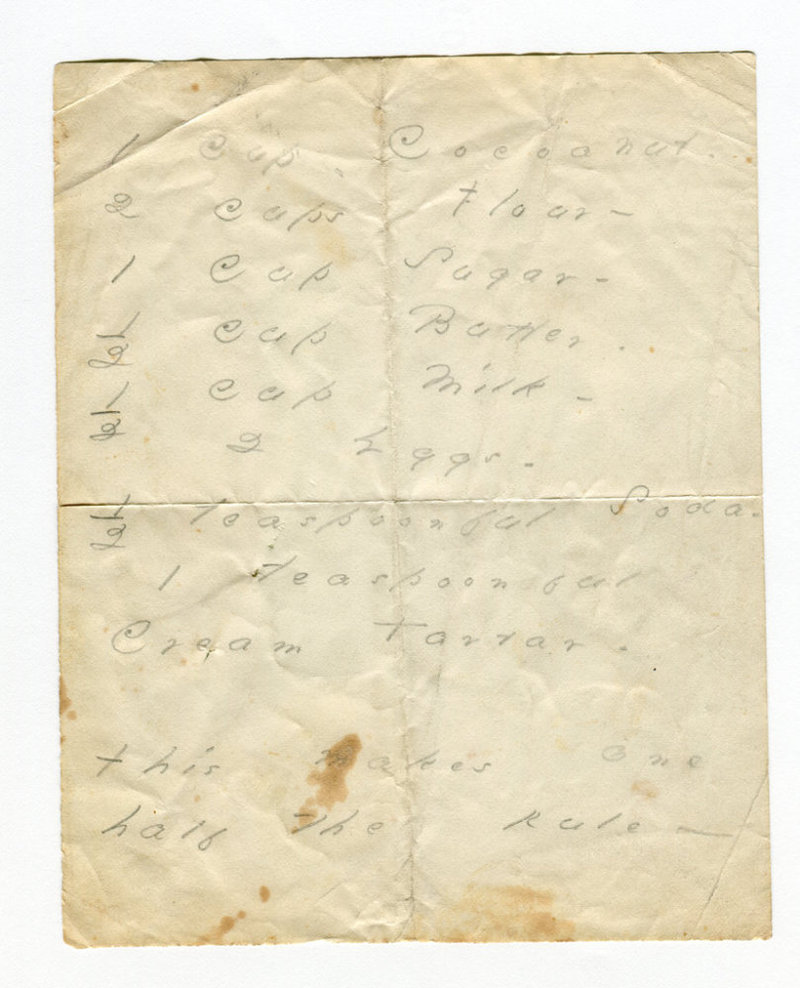

This puts us in the realm of serious literature where sweets, you might assume, are scarcely to be found. But baking constituted a part of the creative process of no less a literary mind than Emily Dickinson, whose handwritten recipe for coconut cake appears above.

That same sheet of a paper’s reverse side, which you can see in our earlier post about it, bears the first lines of her poem “The Things that never can come back, are several.” Dickinson also, as we’ve previously posted here on Open Culture, had her very own recipes for gingerbread, donuts, and something requiring five pounds of raisins called “black cake.”

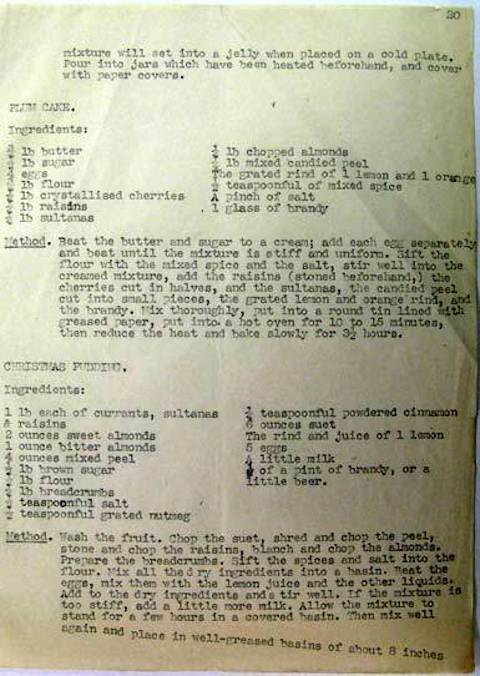

It may seem obvious that women like Toklas and Dickinson, born and raised in the 19th century, would have been expected to learn this sort of thing. But a fair few of the literary men of generations past knew something of their way around the kitchen as well. George Orwell, for instance, wrote an essay on “British cookery,” early in which he states that “in general, British people prefer sweet things to spicy things.” While describing “sweet dishes and confectionery – cakes, puddings, jams, biscuits and sweet sauces” as the “glory of British cookery,” he admits that “the national addiction to sugar has not done the British palate any good.” And so he includes the recipe for a Christmas pudding which, subtle by that standard, calls for only half a pound of the stuff.

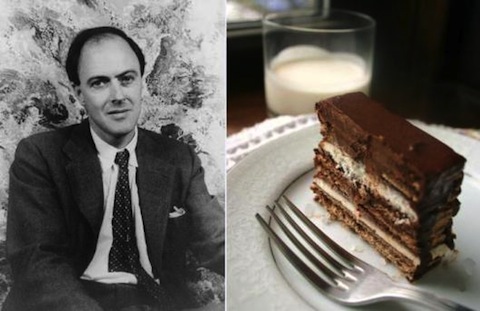

Born a generation after Orwell, Roald Dahl made no secret of his own sugar-addicted British palate. In his book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory Dahl had “dazzled young readers with visions of Cavity-Filling Caramels, Everlasting Gobstoppers, and snozzberry-flavored wallpaper,” writes Open Culture’s own Ayun Halliday. But his own candy of choice was “the more pedestrian Kit-Kat bar. In addition to savoring one daily (a luxury little Charlie Bucket could but dream of, prior to winning that most golden of tickets) he invented a frozen confection called ‘Kit-Kat Pudding,’ ” whose simple recipe is as follows: “Stack as many Kit-Kats as you like into a tower, using whipped cream for mortar, then shove the entire thing into the freezer, and leave it there until solid.”

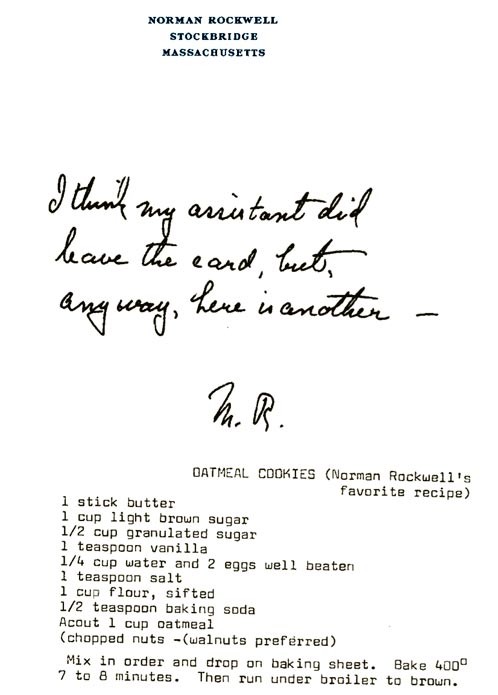

If you’re looking for a slightly more challenging dessert that still comes with a cultural figure’s imprimatur, you might give Normal Rockwell’s favorite oatmeal cookies a try. Going deeper into American history, we’ve also got Thomas Jefferson’s recipe for ice cream, the taste for which he picked up while living in France in the 1780s. That same country’s cuisine also inspired Ernest Hemingway’s fruit pie, meant for summer-camping with one’s pals: “If your pals are Frenchmen,” Hemingway adds, “they will kiss you.” Alas, if anyone has determined the exact recipe for the most famous dessert in all of French literature, Marcel Proust’s memory-triggering madeleines, they haven’t released it to the hungry public.

Related Content:

The Recipes of Iconic Authors: Jane Austen, Sylvia Plath, Roald Dahl, the Marquis de Sade & More

Ernest Hemingway’s Summer Camping Recipes

Wagashi: Peruse a Digitized, Centuries-Old Catalogue of Traditional Japanese Candies

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Leave a Reply