After four years of phenomenal chart success, the band Blondie went on hiatus in 1981. While Debbie Harry pursued the acting she had started in punk rock filmmaker Amos Poe’s works, she also went the solo album route. On paper, this album, KooKoo, must have looked like a surefire hit: Nile Rogers and Bernard Edwards from the band Chic were brought in to write and produce, hot on the heels of their successful resuscitation of Diana Ross’s career the year before. Harry and boyfriend/band member/guitarist Chris Stein wrote tracks as well, and fully indulged in the Black music genres they had already been toying with on Blondie’s Autoamerican, like “Rapture” and “The Tide Is High.”

But here’s where it gets a bit weird, and everything goes off kilter. The choice for the album art and promotional videos was H.R. Giger, the artist who had rattled moviegoers’ brains the previous year with his designs for Ridley Scott’s Alien.

The couple had met Giger in 1980 at a reception for his paintings at New York’s Hansen Gallery.

“There I was introduced to a very beautiful woman, Debbie Harry, the singer of the group Blondie, and her boyfriend, Chris Stein,” Giger said in an interview. “They were apparently excited about my work and asked me whether I would be prepared to design the cover of the new Debbie Harry album.”

Though he didn’t know the group–Giger preferred to listen to jazz–he agreed to the cover and to the promo videos, even directing when the original director didn’t show.

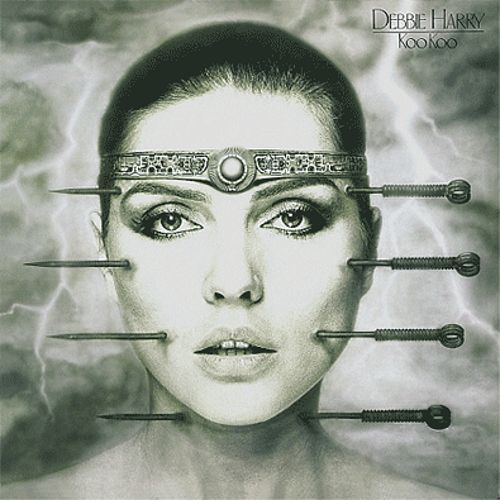

The album cover is probably better known than the music inside, and no wonder: it features Harry’s face pierced horizontally by four spikes. Her expression is ambiguous, possibly ecstatic. It was in one way a throwback to Giger’s other famous record cover, the one for Emerson, Lake, and Palmer’s Brain Salad Surgery. But the cover also would see its influence in films like Hellraiser, the rise of what was called the “modern primitive” movement, and help cultivate the dark masochistic character Harry would play in David Cronenberg’s Videodrome. It was a feeling that would flourish in the decadent ‘80s.

Harry wrote about this in Heavy Metal magazine, which often featured the artist, saying “Giger’s work has a subconscious effect: it engenders the fear of being turned into metal.”

The cover was a taster for more menacing things, however. It’s the videos where Harry goes full Giger. First of all, the blonde hair is gone, replaced by black. And Giger puts Harry in a bodysuit, half flayed-human, half machine. The music videos are simple, performance based, though the sunny, alluring Harry has disappeared and a proto-Goth being has taken her place.

But that leaves us with the music, which one has to admit, is completely unsuited for this design. If Harry had made an album closer to Danielle Dax, for example, then we might have seen one of the oddest mid-career shifts in ‘80s music. Instead the commercial flatlining of the album threw Harry off-track, while Giger went on to be the go-to album artist for metal and punk bands, from the Dead Kennedys to Bloodbath.

Related Content:

How Blondie’s Debbie Harry Learned to Deal With Superficial, Demeaning Interviewers

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

Leave a Reply