Who won the U.S. Civil War? “The north, of course,” you say… but ah… if you did not know the answer, you would have reason to be confused. Who loses a war and puts up statues of its heroes on the victor’s land? In the south, say, in Northern Virginia, you’ll find public shrines to Stonewall Jackson, public highways named for Jefferson Davis, and public schools named after Robert E. Lee and J.E.B. Stewart. These are not historical monuments, i.e. preserved battlefields, graveyards, or historic homes. They were erected decades after the war. You’ll find them in California, Oregon, and Washington state, which did not exist at the time.

Next question: who did the Confederacy fight in the Civil War? The Union, of course. But the leaders of the region also warred with another enemy, as they had for over two hundred years: millions of enslaved people kept in brutal subjection. In many respects, they won this war, though they lost the privileges of legal slavery. Once Andrew Johnson came to power, the south reinstituted conditions that were often more or less the same for Black people as they had been before the war. Grant struggled to reverse the tide, but Reconstruction ultimately failed.

This is the victory the south commemorated when organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of Confederate Veterans put up monuments to southern generals all over the country. It is the victory invoked by the Battle Flag of the Army of Northern Virginia (or the “Confederate Flag”). A defiance of multi-racial democracy and a government that serves the needs of all its citizens; a menacing promotion of white supremacist mythology, maintained with public funds on public lands. Those symbols include:

- 780 monuments, more than 300 of which are in Georgia, Virginia or North Carolina;

- 103 public K‑12 schools and three colleges named for Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis or other Confederate icons;

- 80 counties and cities named for Confederates;

- 9 observed state holidays in five states; and

- 10 U.S. military bases.

But, no, one might say, these are observances for the southern dead, who were, after all, Americans too. This is what we’ve heard, over and over. It was a hoary old story when W.E.B. Du Bois heard it in the early decades of the twentieth century. “Lost Cause” ideology had done its work, flooding the culture with sympathetic portrayals of the Confederacy, a wave of propaganda that reached its apex in the spectacle of 1915’s Birth of a Nation (first titled The Clansman), responsible for resurrecting the Ku Klux Klan.

The story went something like this: “No nobler young men ever lived; no braver soldiers ever answered the bugle call nor marched under a battle flag,” proclaimed southern industrialist Julian Carr at the 1913 dedication of Confederate statue Silent Sam, which stood on the campus of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill until activists tore it down recently. “They fought, not for conquest, not for coercion, but from a high and holy sense of duty. They were like the Knights of the Holy Grail.”

Carr goes on like this at length, reciting poetry and making constant references to Greek heroes and gods. His purpose, he says, is to memorialize “the Sacred Cause.” But he never says what that cause is, though he has many exalted words for “the noble women of my dear Southland, who are to-day as thoroughly convinced of the justice of that cause.” The speech is boilerplate Confederate apologism: an almost hysterically bombastic defense of the south that never once mentions slavery.

Yet in an odd moment, Carr breaks off—during a rant about “what the Confederate soldier meant to the welfare of the Anglo Saxon race”—to make a “rather personal… allusion” for seemingly no reason:

One hundred yards from where we stand, less than ninety days perhaps after my return from Appomattox, I horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady, and then rushed for protection to these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison, and for thirty nights afterwards slept with a double-barrel shot gun under my head.

What does it say about his audience that Carr thinks this admission reflects well on him? Du Bois understood it. He had diagnosed the fear and violent hatred men like Carr embodied and seen their cowardice and desperate overcompensation. “They preach and strut and shout and threaten,” he wrote in The Souls of White Folk, “crouching as they clutch at rags of facts and fancies to hide their nakedness, they go twisting, flying by my tired eyes and I see them ever stripped—ugly, human.”

Du Bois knew what Confederate monuments were meant to represent. In 1931, he cut to the heart of the matter in brief remarks published in The Crisis (top). “Du Bois pushes right back against the myth of the Lost Cause,” writes historian Kevin M. Levin. “He refuses to draw a distinction between the Confederate government and men in the ranks,” as represented by statues like Silent Sam. “Du Bois clearly understood that as long as white southerners were able to mythologize the war through their monuments, African Americans would remain second class citizens.”

He did not refer to monuments put up in Confederate cemeteries, as many had been immediately after the war, but to the hundreds of statues and other memorials erected in prominent places of government beginning around 1900. “All of these monuments were there to teach values to people,” says Mark Elliott, professor of history at University of North Carolina, Greensboro. “That’s why they put them in the city squares. That’s why they put them in front of state buildings.” It’s why there are Confederate statues in the U.S. Capital, gifts to the nation from southern states, gladly accepted.

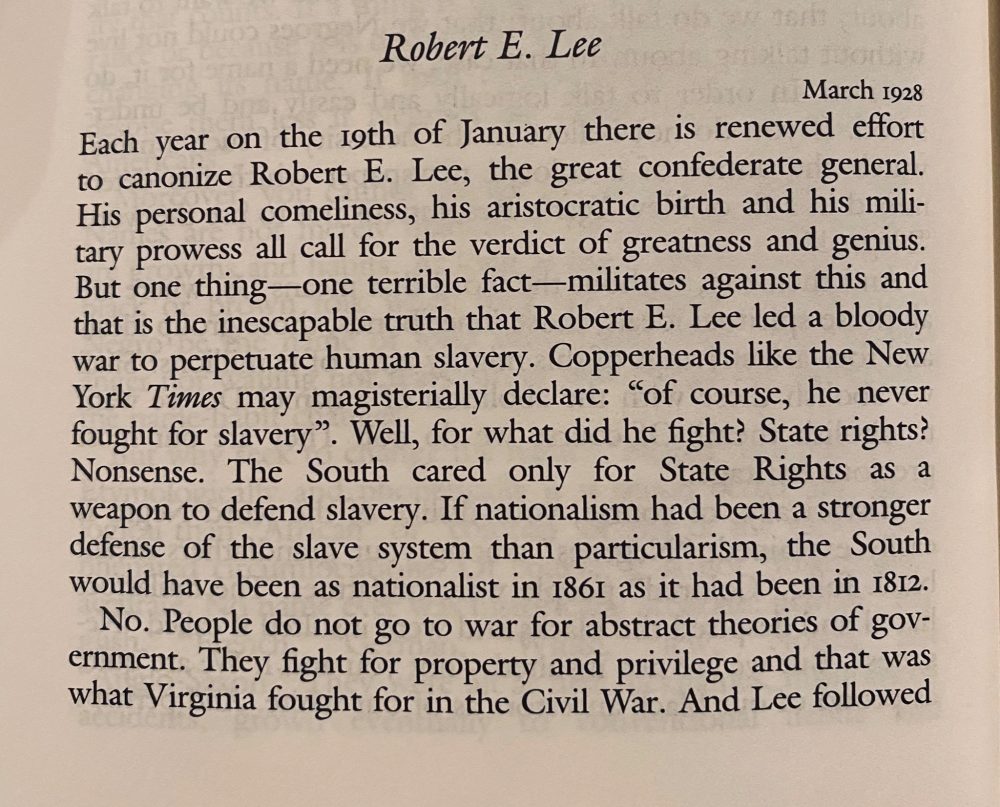

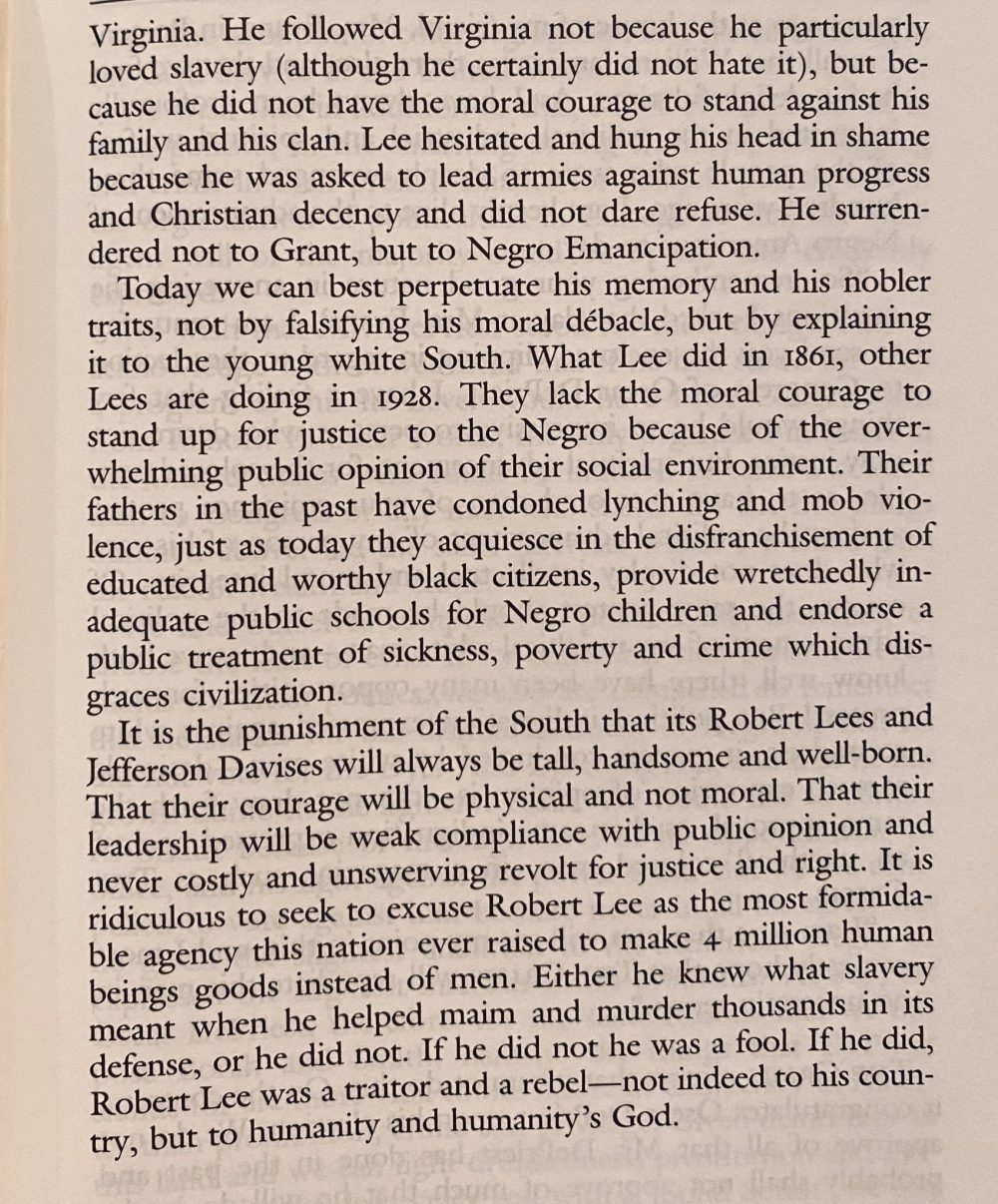

Three years earlier, Du Bois had written many choice words about attempts to deify Confederate leaders like Robert E. Lee (who himself opposed monuments). He also countered the argument that the war was about “States Rights” in one incisive sentence: “If nationalism had been a stronger defense of the slave system than particularism, the South would have been as nationalist in 1861 as it had been in 1812.” None of the high-flown rhetoric about “the cause” of governing principles had anything to do with it, Du Bois argues. “People do not go to war for abstract theories of government. They fight for property and privilege.”

One statue in North Carolina, Du Bois notes wryly in his Crisis remarks, goes so far as to claim that Confederate soldiers “Died Fighting for Liberty!” This would not strike Lost Cause defenders like Carr as ironic. They too fought for liberty, of a kind—the freedom to punish, kill, imprison, exploit, disenfranchise, and otherwise terrorize and impoverish Black Americans at will.

Related Content:

The Civil War & Reconstruction: A Free Course from Yale University

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

So Josh, California didn’t exist before the Civil War?

well done!

I would be grateful for less click-baity titles. Thanks.

In 1849, Californians sought statehood and, after heated debate in the U.S. Congress arising out of the slavery issue, California entered the Union as a free, nonslavery state by the Compromise of 1850. California became the 31st state on September 9, 1850.

Josh,

I agree with you that the Confederate statues should be taken down and removed out of sight. Let’s try to forget that time and move on as Americans.

You are only making things worse by this and other articles on the present situation

Not only was California annexed in 1850, the southern counties had so many ex-Southerners and Confederate sympathizers that a military base was built in Los Angeles’ South Bay in case of a Confederate uprising.

…Of course, Los Angeles eventually got rid of its Confederate monuments. The last ones of which I’m aware were in privately owned cemeteries and were quietly removed years ago.

If you listen to Thomas Sowell and his explanation of schools, then and now, you will find that today’s schools, indeed, have not serviced our minority or our majority communities well. In the past the segregated schools were very good and served our minorities and the majority of minorities were against desegregation. We desegregated to the point of bringing almost all of our schools down to a low equality. Charter and private schools are trying to change this so it’s no wonder the government and the teacher’s unions are against charter schools. Look forward people, glance at the past, but embrace the future.