“Pics or it didn’t happen,” says the Internet, a phrase typically “used in jest,” writes Erin Ratelle at Space and Culture, as “a counter to an outrageous claim of events. However, its root is predicated on the notion that media is integral to being or existence,” that we must record everything. Such implicit understanding was only in its infancy in 1918, when the influenza outbreak known as the Spanish Flu began, which perhaps goes some way toward explaining why a viral pandemic that killed millions around the world—far more than World War I—is so underrepresented in the historical record.

These days if a Utah county commission meeting about masks for children gets thronged by unmasked protesters, we get almost-instant video at The Washington Post. Images filter out through Twitter and Facebook, or move in the other direction, and millions see them within hours. During the 1918 flu pandemic, unmasked protesters against mask laws also abounded, but coverage of their stunts took months to move from local papers to national outlets, who eventually covered the San Francisco Anti-Mask League’s strident refusals. The devastating epidemic, however, estimated to have infected one third of the world, was almost entirely absent from silent film at the time.

Cinema of all kinds avoided the subject, writes Bryony Dixon at the British Film Institute (BFI): “It’s astonishing to think how invisible the first pandemic in the time of cinema is from the film record. Apart from one informational film, which survives in the BFI National Archive, the influenza pandemic of 1918/1919 doesn’t appear in British film at all. There were no newsreel reports, and no fiction films were made that even mentioned the three waves of the pandemic that struck the country in the final year of the First World War and would kill 200,000 people” in the UK and 500 million worldwide.

This does not mean there are no films about plague and pestilence from the time. But the present seemed to have been too painful. Filmmakers looked back to Boccaccio, one of whose Decameron stories was adapted for the screen. “It must certainly have been easier,” Dixon writes, “for silent era audiences to contemplate pandemic within the moral framework of the medieval period.” Edgar Allan Poe’s Masque of the Red Death was adapted by Fritz Lang in a screenplay for Otto Rippert’s 1919 The Plague in Florence. F.W. Murnau’s 1922 Nosferatu is, arguably, about disease, as is its source, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. But fiction and documentary mostly stayed mum about the deadly flu pandemic.

In 1918, the War had nearly every European nation (and the U.S. at that point) preoccupied. Government control over major media outlets censored coverage of the disease, ostensibly to avoid a panic. The staggering death tolls of war and infection were overwhelming. A political narrative took shape to suggest a culprit, Spain, which was neutral during WWI, and the first country to begin covering the disease in their press (hence the “Spanish Flu,” which did not originate in Spain). The one exception to the blackout in the BFI archive is the short informational film at the top, Dr. Wise on Influenza.

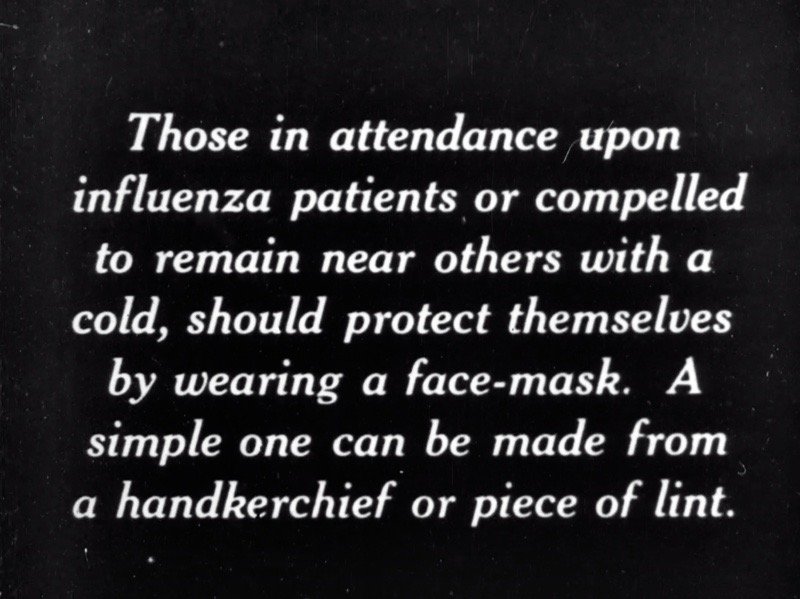

Produced under the auspices of Sir Arthur Newsholme, the Chief Medical Officer of the Local Government Board (LGB), the film arrived a little too late to do much good after the second wave of infections began in 1919, and it was not widely distributed. The short film promotes wearing masks, and it tells a very familiar story, as Dixon explains:

The ‘doctor’ uses the device of a fictional story in which a rather dim Mr Brown coughs and sneezes over colleagues in the office and the street, before going on to infect 100 people at a theatre (we see a rare early glimpse of the Empire Leicester Square, which was showing a musical, The Lilac Domino).

It doesn’t end well for Mr Brown, and an on-screen title lists the grim totals of deaths in British cities, just as we’ve become used to seeing today. Other parallels with the current situation are spooky: the prime minister, Lloyd George, like Boris Johnson, was hospitalised for days with the virus, and an anxious nation was told it was ‘touch and go’ for a while.

History has been rhyming all over the place lately, maybe the most poetic thing about the ugly times we’re living in. As much as we might have believed that the world, or our particular corner of it, had changed, we’re finding out how little progress we’ve actually made. Ironically, one of the most remarkable differences between the early 21st century and everything that came before—the omnipresence of cameras and video—has accelerated these realizations. We can now witness, in ways no one possibly could have in 1919, just how much of the past we’re dragging along behind us.

Related Content:

What Happened When Americans Had to Wear Masks During the 1918 Flu Pandemic

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

“Spanish Flu”

Offensive much?