For decades, would-be black military pilots saw their possible future careers “canceled,” as they say, by racism in the segregated U.S. armed forces. Black servicemen “were denied military leadership roles and skilled training,” writes the official Tuskegee Airmen site, “because many believed they lacked qualifications for combat duty.” Aspiring airmen would finally, after campaigning since World War I, be given the chance to train and fly missions in the early forties, after “civil rights organizations and the black press exerted pressure that resulted in the formation of an all African-American pursuit squadron based in Tuskegee, Alabama.”

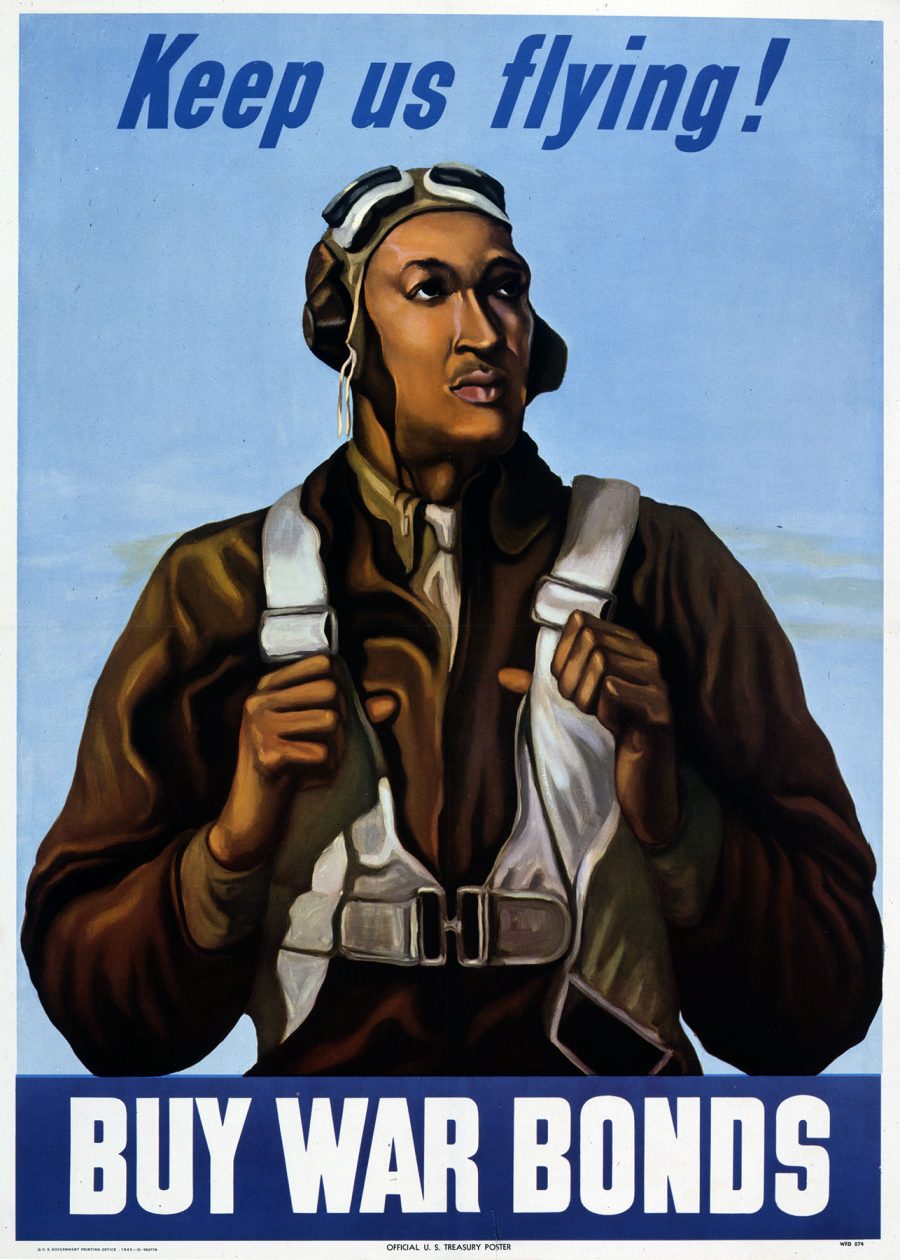

Actually trained on a dozen airfields around Tuskegee University, the airmen in the program “came away from those godforsaken Alabama fields with the unwavering belief that their newfound abilities might just help overcome prejudice, hearsay, and plain old dislike,” says Morgan Freeman in his voiceover narration for “Red Tails,” the short documentary above. The “Red Tails” or “Red Tail Angels,” as they were called after the distinctive color of their planes’ tails, roundly surpassed all expectations, becoming some of the most successful fighter pilots of the war.

“They would not be denied, despite the fact that they were unwelcome, unappreciated, and very much underestimated,” says Freeman. This is an understatement. The belief that African Americans lacked the capacity for complicated flight training was so prevalent that even the progressive Eleanor Roosevelt would give voice to it (in a demonstration to disprove it) when she visited the budding program in April 1941. “Can Negroes really fly airplanes?” she cheerfully asked the program’s head Charles “Chief” Anderson. He was obliged to give her a demonstration in his Piper J‑3 Cub, against the objections of her Secret Service detail.

Soon afterward, the first Negro Air Corps pilots began training, and the enlisted men chosen for the program became officers. Partly because of turnover among white senior officers in the program, who used it as a stepping stone to promotions and left after a few months, progress was slow. It wasn’t until September that Captain Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. was given the go-ahead for a solo flight, and not until April 1943 that the first squadron, the 99th, given combat clearance. Their story has passed into legend, from the claim that the Red Tails never lost a single bomber to the dramatic recreations of George Lucas’ Red Tails.

Later declassified documents appear to show that they had, in fact, lost bombers, like every other fighter group in the war. The fact hardly tarnishes the Tuskegee Airmen’s many medals or their prolifically attested skill and courage. It wouldn’t be until three years after the war ended that the military was finally desegregated, though the airmen themselves were lauded, promoted, and sought out by private industry when they returned to civilian life. Robert Friend, who died in 2019 at the age of 99, went on to serve in Korea and Vietnam, retired as a lieutenant colonel, worked on space launch vehicles, and formed his own aerospace company.

Charles McGee, who features in the short video documentary, just turned 100 this past February, and received a promotion to brigadier general. His reaction was ambivalent: “At first I would say ‘wow,’ but looking back, it would have been nice to have had that during active duty, but it didn’t happen that way. But still, the recognition of what was accomplished, certainly, I am pleased and proud to receive that recognition.”

Davis, the Tuskegee program’s first solo pilot and commander of the 99th Pursuit Squadron “was instrumental in drafting the Air Force plan to implement” desegregation in 1948, and he would become the Air Force’s first African American general. Davis’ father, it so happens, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., had been the first black general in the U.S. Army. The Tuskegee Airmen were undoubtedly pioneers, but they were also part of a long tradition of black Americans who fought for the U.S. since its beginnings, “despite the fact,” as Freeman says, “that they were unwelcome, unappreciated, and very much underestimated.”

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply