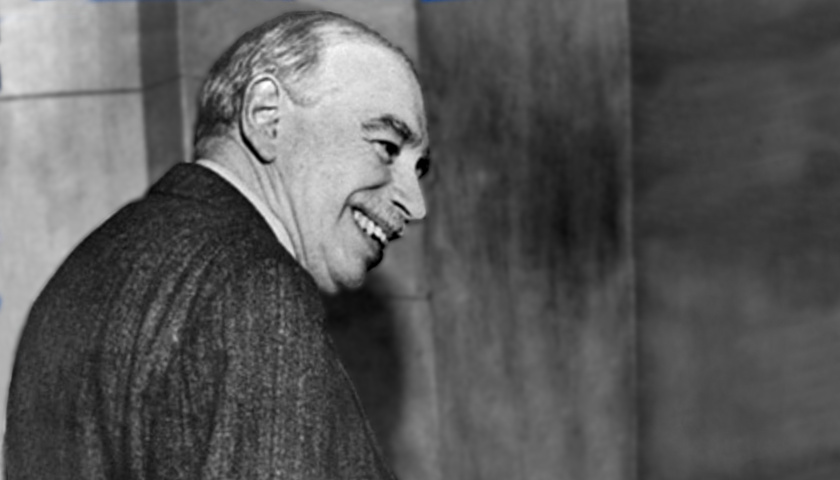

Image by IMF, via Wikimedia Commons

That which stands first, and is most to be desired by all happy, honest and healthy-minded men, is ease with dignity.

—Cicero, Pro Sestio, XLV., 98

There is much to admire in Roman ideas about the use of leisure time, what Michel Foucault referred to as “the care of the self.” The Latin words for work and leisure themselves give us a sense of what should have priority in life. Negotium, or business, is a negation, with the literal meaning of “the nonexistence of leisure” (otium). The English word—considered in its parts as “busy-ness”—doesn’t really sound much more appealing.

The notion that everyone, not just a propertied elite, however, should be entitled to leisure time came about only relatively recently—mostly advocated by radicals and trade unionists. In the U.S., anarchists and striking workers in Chicago fought against police in 1886 during the Haymarket Affair to achieve “Eight Hours for Work, Eight Hours for Rest, Eight Hours for What We Will.” In 1912, women-led immigrant strikers chanted “Bread and Roses” in Lawrence, Massachusetts, proclaiming their right to more than bare survival.

After the achievement of the 40-hour workweek, paid vacations, and other labor concessions, many influential figures believed that egalitarian access to leisure would only increase in the 20th century. Among them was economist John Maynard Keynes, who forecast in 1930 that labor-saving technologies might lead to a 15-hour workweek when his grandchildren came of age. Indeed, he titles his essay, “Economic Possibility for our Grandchildren.”

Writing at the start of the Great Depression, Keynes finds reason for optimism. “We are suffering,” he writes, “not from the rheumatics of old age, but from the growing-pains of over-rapid changes, from the painfulness of readjustment between one economic period and another.” Keynes’ essay concerns what he calls the “economic problem,” which is not only the problem of mass unemployment but also, in his estimation, the ability of capitalism to provide a decent standard of living for everyone. He did not see its failure to do so as evidence of a more fundamental dysfunction:

[T]his is only a temporary phase of maladjustment. All this means in the long run that mankind is solving its economic problem. I would predict that the standard of life in progressive countries one hundred years hence will be between four and eight times as high as it is to-day. There would be nothing surprising in this even in the light of our present knowledge. It would not be foolish to contemplate the possibility of afar greater progress still.

Many economists shared Keynes’ optimism through the 1970s, “a time when revolutionary change still seemed like an imminent possibility,” writes John Quiggan, professor of economics at the University of Queensland.” Utopian ideas were everywhere, exemplified by the Situationist slogan of 1968: ‘Be realistic. Demand the impossible.’” Cult figures like Buckminster Fuller explained, as had Keynes decades earlier, how technology could free everyone from the tyranny of the labor market and the scourge of “useless jobs.”

Keynes and others made a “case for leisure, in the sense of free time to use as we please, as opposed to idleness”—a distinction that draws from the ancient philosophers. “But Keynes offered something quite new: the idea that leisure could be an option for all, not merely for an aristocratic minority.” He was, obviously, mistaken. “At least in the English-speaking world,” Quiggan writes, “the seemingly inevitable progress towards shorter working hours has halted. For many workers it has gone into reverse.”

That has certainly been the case for the majority of workers in the U.S., at least before the novel coronavirus led to mass layoffs and reduced hours. What happened? For one thing, the ascension of neoliberal economics in the late 1970s, and the elections of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, began a long slow decline of organized labor. “Employers have had increasing desire for workers to work long hours,” says Juliet Schor, professor of sociology at Boston College. “And workers haven’t had the power to resist that upward pressure.”

Keynes’ predictions resonated with NPR’s David Kestenbaum, who interviewed some of Keynes’ descendants, the closest thing he had to grandchildren, in a short segment on Planet Money in 2015. One Keynes relation points out the irony that the man himself “died from working too hard.” How can those of us who aren’t globally famous economists help end the tyranny of overwork? Maybe a lot more striking workers making demands; maybe a universal basic income or something like Bhutan’s “gross domestic happiness” index?

Keynes may have erred in his predictions of the future (though he seems to have understood the needs of his moment well enough), but he may not have been wrong to view the economic turmoil of his time as a radical opportunity for utopian change and better living for everyone. Overturning the dire conditions of the present for our own grandchildren will require not only hard work, but the leisure to do some visionary futurist thinking. Read Keynes’ full essay here.

Related Content:

An Animated Introduction to Economist John Maynard Keynes

The Case for a Universal Basic Income in the Time of COVID-19

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply