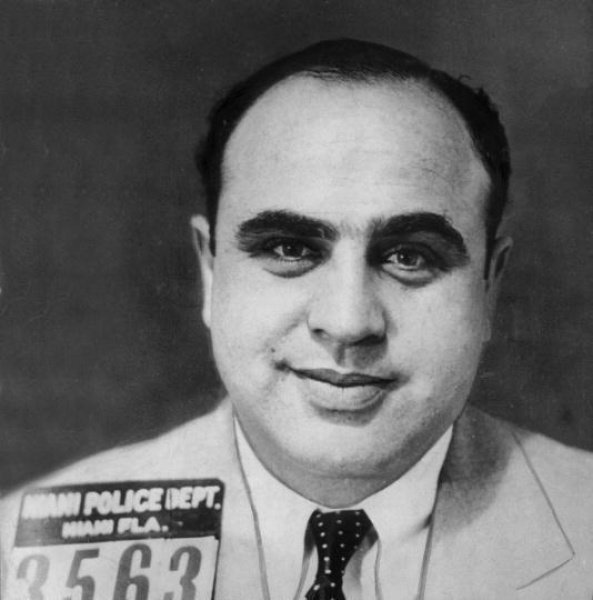

In response to the words “American gangster,” one name comes to mind before all others: Al Capone. (Apologies to Ridley Scott.) Though few Americans could now describe the full scope of his empire’s criminal activities, many know that he grew that empire bootlegging during Prohibition and that he was eventually brought down on the relatively mild charge of tax evasion. A media spectacle by the standards of the day, the trial that convicted Capone in 1931 was in some sense the natural last act of his publicity-commanding career. Most Caponeologists place the beginning of the mob boss’ fall at the 1929 “Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre” of seven of Capone’s rivals. Later that year came the stock market crash that set off the Great Depression, which offered Chicago’s “Public Enemy No. 1” one last chance to win back that public’s favor.

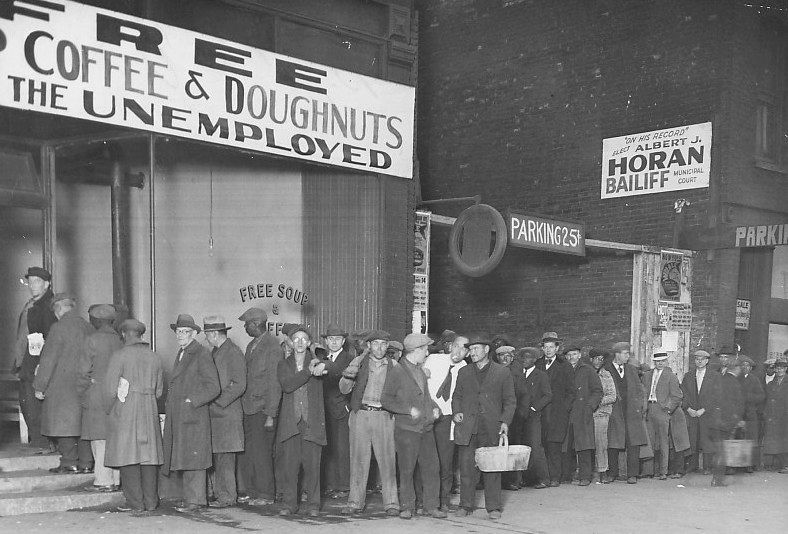

Having long traded on a Robin Hood-esque image, Capone opened a soup kitchen in his home base of Chicago to serve the unfortunates suddenly dispossessed by the devastated American economy. “Capone’s soup kitchen served breakfast, lunch and dinner to an average of 2,200 Chicagoans every day,” writes History.com’s Christopher Klein. “Inside the soup kitchen, smiling women in white aprons served up coffee and sweet rolls for breakfast, soup and bread for lunch and soup, coffee and bread for dinner. No second helpings were denied. No questions were asked, and no one was asked to prove their need.”

Capone’s willingness to satisfy human needs and desires outside the law kept him rich, and thus more than able to run such an operation, even as the Depression set in; still, he “may not have paid a dime for the soup kitchen, relying instead on his criminal tendencies to stockpile his charitable endeavor by extorting and bribing businesses to donate goods.”

Capone’s soup kitchen may have helped keep Chicago fed, but it could only do so much to clean up his deteriorating public image, associated as it had become with smuggling, extortion, and violence. “Capone’s soup kitchen closed abruptly in April 1932,” writes Mental Floss’ Shoshi Parks. “The proprietors claimed that the kitchen was no longer needed because the economy was picking up, even though the number of unemployed across the country had increased by 4 million between 1931 and 1932.” Two months later, “Capone was indicted on 22 counts of income tax evasion; the charges that eventually landed him in San Francisco’s Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary. Though Capone vowed to reopen his soup kitchen during his trial, its doors stayed shut.” You can learn more about Capone’s soup kitchen at My Al Capone Museum and The Vintage News, and even visit its location at 935 South State Street today — though you won’t find any operation more ambitious than a parking lot.

via Mental Floss

Related Content:

A Map of Chicago’s Gangland: A Cheeky, Cartographic Look at Al Capone’s World (1931)

Yale Presents an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

1,600 Rare Color Photographs Depict Life in the U.S During the Great Depression & World War II

Confidence: The Cartoon That Helped America Get Through the Great Depression (1933)

What Prisoners Ate at Alcatraz in 1946: A Vintage Prison Menu

New Archive Presents The Chicagoan, Chicago’s Jazz-Age Answer to The New Yorker (1926 to 1935)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Leave a Reply