Romantic poets told us that great art is eternal and transcendent. They also told us everything made by human hands is bound to end in ruin and decay. Both themes were inspired by the rediscovery and renewed fascination for the arts of antiquity in Europe and Egypt. It was a time of renewed appreciation for monumental works of art, which happened to coincide with a period when they came under considerable threat from looters, vandals, and invading armies.

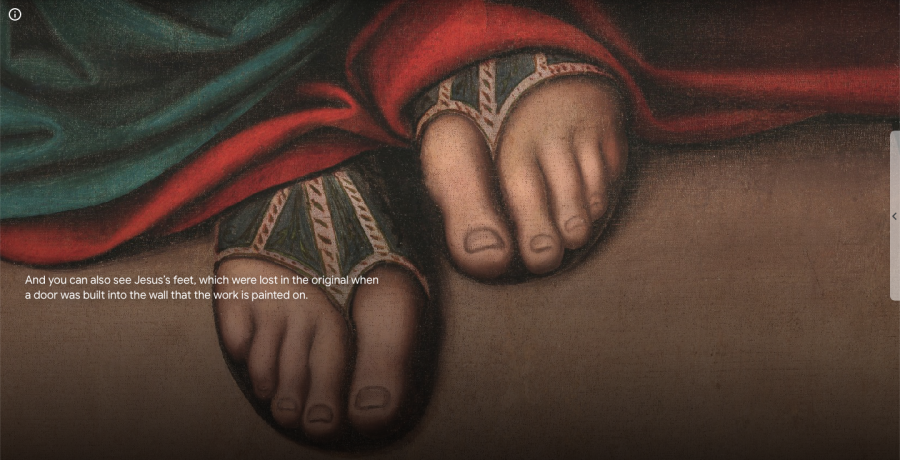

One work of art that appeared on the itinerary of every Grand Touring aristocrat, Leonardo’s da Vinci’s fresco The Last Supper in Milan, was made especially vulnerable when the refectory in which it was painted became an armory and stable for Napoleon’s troops in 1796. The soldiers scratched out the apostles’ eyes and lobbed rocks at the painting. Later, in 1800, Goethe wrote of the room flooding with two feet of water, and the building was also used as a prison.

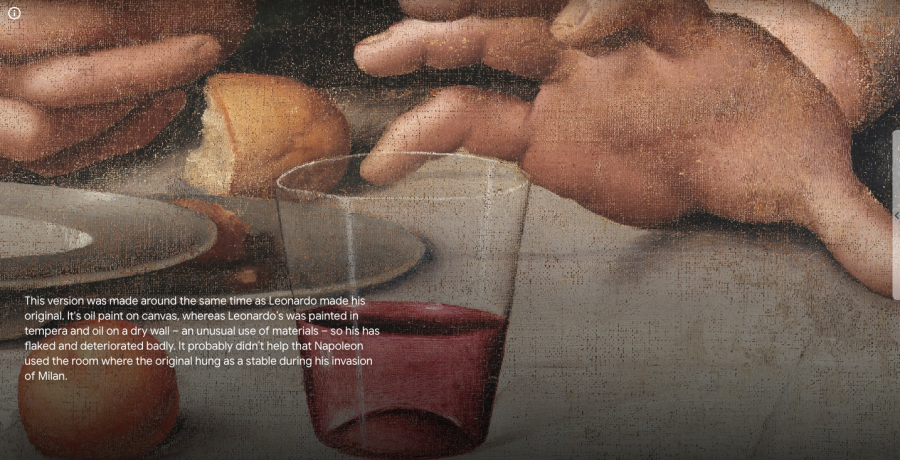

As every curator and conservationist knows well, grand ideas about art gloss over important details. Art is bound to particular cultures, histories and materials. One of Leonardo’s most influential frescoes during the Renaissance, for example, almost completely melted right after he finished it, due to his insistence on using oils, which he also mixed with tempera in The Last Supper. Just a few decades after that painting’s completion, one Italian writer would describe it as “blurred and colorless compared with what I remember of it when I saw it as a boy.”

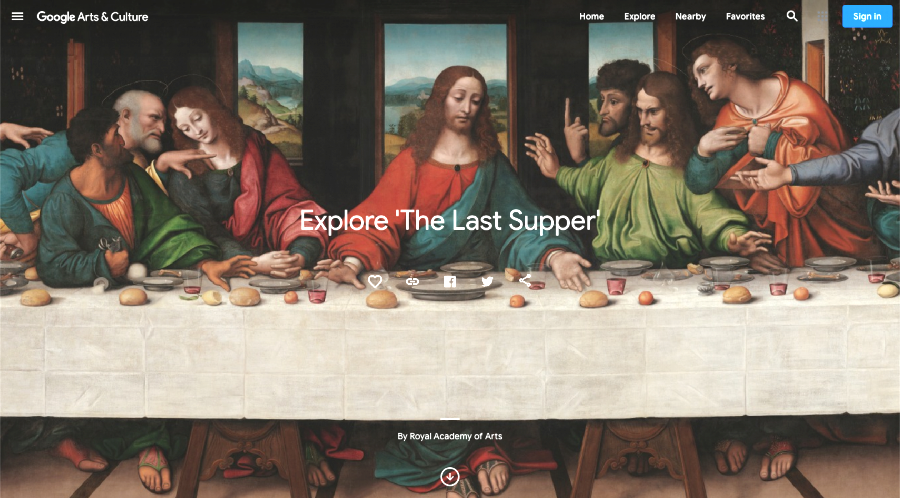

Historical decay is one thing. Recent fires at Brazil’s National Museum and Notre Dame served as stark reminders that accidents and poor planning can rob the world of cherished cultural treasures all at once. Institutions have been digitizing their collections with as much detail and precision as possible. For their part, England’s Royal Academy of Arts has partnered with Google Arts & Culture to render several of their most prized works online, including a copy of The Last Supper on canvas, made by Leonardo’s students from his original work.

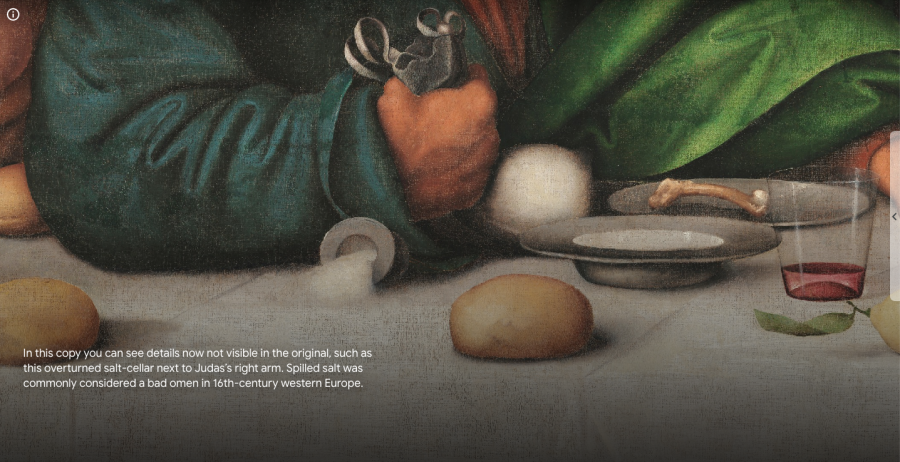

More than any other contemporary description of the painting, this faithful copy, probably made by artists who worked on the fresco itself, provides art historians “key insights into the long-faded masterwork in Milan,” and lets us see the vivid shades that awed its first viewers. Presented in “Gigapixel clarity,” notes Artnet, the huge digital image with its “ultra high resolution” was “made possible by a proprietary Google camera.” As you zoom in to the tiniest details, facts appear about the painting and its larger, more battered original in Milan.

It is either a “miracle” that The Last Supper has survived, as Áine Cain writes at Business Insider, or the result of an “unending fight” to preserve the work, as Kevin Wong details at Endgadget. Or maybe some mysterious mixture of chance and near-heroic effort. But what has survived is not what Leonardo painted, but rather the best reconstruction to emerge from centuries of destruction and restoration. Get closer than anyone ever could to a facsimile of the original and see details from Leonardo’s work that have left no other trace in history. Explore it here.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I am pretty sure Leonardo wasn’t painting in “tempura.”

Tempura = japanese fish dish.

Tempera = painting method.

Brian, how did you end up reading this article? Baffled