Every once in a while, a prominent artist will offer the advice that you should quit your day job and never look back. In some fields, this may be possible, though it’s becoming increasingly difficult these days, which may explain the reception Brian Eno gets when he tells art school students “not to have a job.” Eno admits, “I rarely get asked back.” In a letter to his anxious mother, Gustave Flaubert, railed against “those bastard existences where you sell suet all day and write poetry at night.” Such a life, he wrote, was “made for mediocre minds.”

Sure, if you can swing it, by all means, quit your job. Most poets throughout history—save the few with independent means or wealthy patrons—haven’t had the luxury. Poetry may never pay the bills, but that shouldn’t stop a poet from writing. It didn’t stop T.S. Eliot, who worked as an editor (he rejected George Orwell’s Animal Farm) and a bank clerk (he turned down a fellowship from the Bloomsbury group). It did not stop William Carlos Williams, the doctor, nor Wallace Stevens, who spent his days in the insurance game, nor Charles Bukowski, though he’d never recommend it….

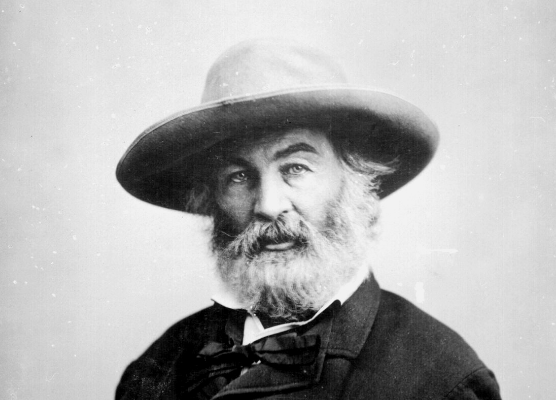

Then there’s ultimate journeyman poet Walt Whitman, who left school at 11 to get a job and variously throughout his life “worked as a school teacher, printer, newspaper editor, journalist, carpenter, freelance writer, civil servant, and Union Army nurse in Washington D.C. during the Civil War,” as the Library of Congress (LOC) noted for the 200th anniversary of the poet’s 1819 birth. The LOC holds “the world’s largest Walt Whitman manuscript collection” and last year they announced a volunteer campaign to transcribe thousands of unpublished documents.

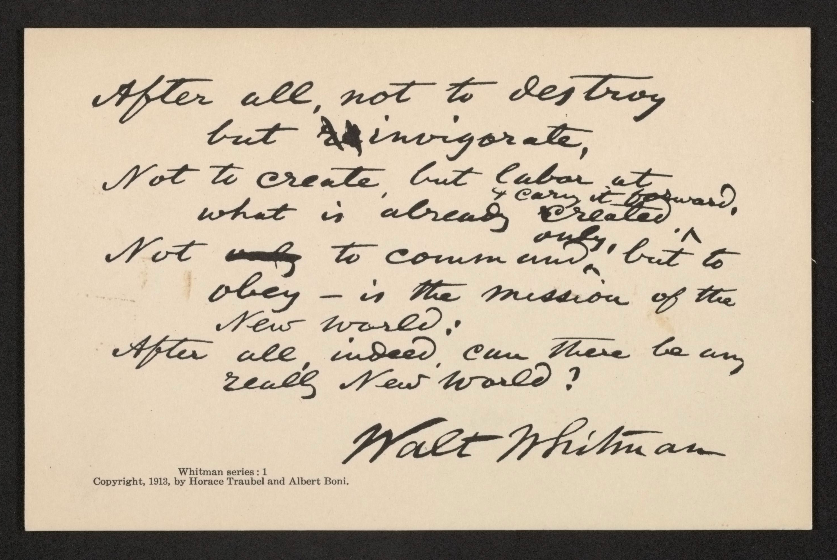

Whitman offered his own possibly dubious advice to aspiring writers—“don’t write poetry”—but he himself never stopped writing, no matter the demands of the day. He also advised, “it is a good plan for every young man or woman having literary aspirations to carry a pencil and a piece of paper and constantly jot down striking events in daily life. They thus acquire a vast fund of information.” Whitman’s “jottings” include typed and handwritten letters, original copies of poems, drafts of essays and reviews, and more.

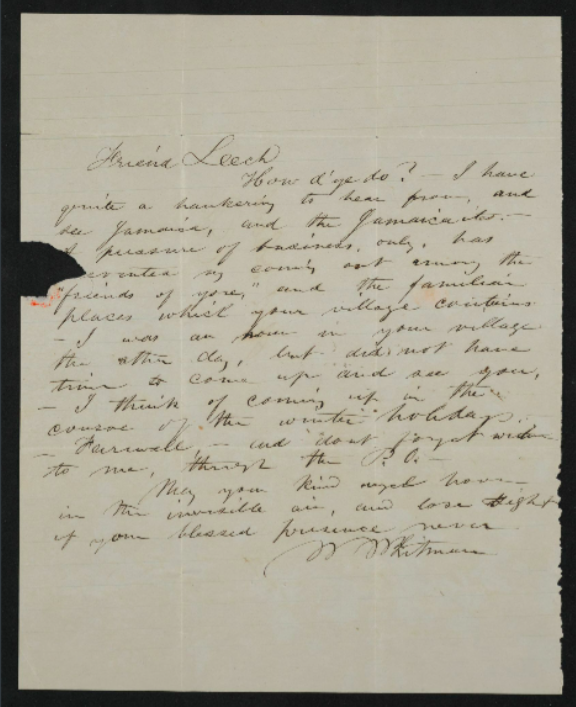

His prose is always lively and robust, full of exhortations, exaltations, and admixtures of the high literary language and casual talk of city streets that were his hallmark. Witness the wild swings in tone in his brief letter to Abraham P. Leech (above) circa 1881:

Friend Leech,

How d’ye do? — I have quite a hankering to hear from and see Jamaica, and the Jamaicaites. — A pressure of business only, has prevented my coming out among the “friends of yore” and the familiar places which your village contains. –I was an hour in your village the other day, but did not have time to come up and see you,–I think of coming up in the course of the winter holidays.–Farewell–and don’t forget write to me, through the P.O. May your kind angel hover in the invisible air, and lose sight of your blessed presence never.

Whitman

There are many, many more such documents remaining to be transcribed among the close to 4000 in the LoC’s digitized Whitman collection. “More than half of those have been completed so far,” writes Mental Floss, and roughly 1860 transcriptions still need to be reviewed. Anyone can read the documents that need approval and officially add them to the Whitman archive.” This is a very worthy project, and it may or may not feel like work to volunteer your time deciphering, reading, and transcribing Whitman’s ebullient hand.

The question may still remain: How did Whitman acquire the physical and mental stamina to get so much excellent writing done and still hold down steady gigs to make the rent? Perhaps a series of guides called “Manly Health and Training” that he wrote between 1858 and 1860 hold a clue. The poet recommends routine trips to the “gymnasium” and a diet of meat, “to the exclusion of all else.” For those “students, clerks” and others “in sedentary and mental employments”—including the “literary man”—he has one word: “Up!”

As with all such pieces of advice, results may vary. Enter the two huge manuscript archives—“Miscellaneous” and “Poetry”—at the Library of Congress digital collections and peruse, or transcribe, as much of Whitman’s endless stream of writing as you like.

Related Content:

Walt Whitman’s Poem “A Noiseless Patient Spider” Brought to Life in Three Animations

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Hello’

Thank you for the interesting article. I missed the part that shows me where I can sign up to volunteer.

Any links to that?

Thanks again.

Carroll Woods

This is very misleading. Where exactly can I sign up? I see nothing listed here.

From the artical in question … “…Anyone can read the documents that need approval and officially add them to the Whitman archive.…” and “Enter the two huge manuscript archives—“Miscellaneous” and “Poetry”—at the Library of Congress digital collections and peruse, or transcribe, as much of Whitman’s endless stream of writing as you like.” The link is in the last paragraph.

It’s now 2023. Are volunteers still needed for this worthy task?

If yes, where can i find detailed instructions on how to access documents that have never been transcribed?

How does a volunteer send transcriptions?