Plato’s ideal of philosopher-kings seems more unlikely by the day, but most modern readers of The Republic don’t see his state as an improvement, with its rigid caste system and state control over childbearing and rearing. Plato’s Socrates did not love democracy, though he did argue that men and women (those of the guardian class, at least) should receive an equal education. So too did many prominent European political philosophers of the 18th and 19th centuries, who had at least as much influence on world affairs as Plato did on Athens, for better and worse.

One such thinker, Jeremy Bentham, is often remembered as the inventor of the panopticon, a dystopian prison design that makes inmates internalize their own surveillance, believing they could be watched at any time by unseen eyes. Made infamous by Michel Foucault in the mid-20th century, the proposal was first intended as humane reform, consistent with the tenets of Bentham’s philosophical innovation, Utilitarianism, often associated with his most famous disciple, John Stuart Mill.

Bentham may also have been one of the most progressive secular philosophers of any age—espousing full political rights for everyone—by which he actually meant everyone, not only European landowning men. “In his own time,” writes Faramerz Dabhoiwala at The Guardian, Bentham “was celebrated around the globe. Countless practical efforts at social and political reform drew inspiration from him. […] He was made an honorary citizen of revolutionary France, while the Guatemalan leader José del Valle acclaimed him as ‘the legislator of the world.’ Never before or since has the English-speaking world produced a more politically engaged and internationally influential thinker across such a broad range of subjects.”

Bentham took the role seriously, though there may be the seeds of a morbid practical joke in his last philosophical act.

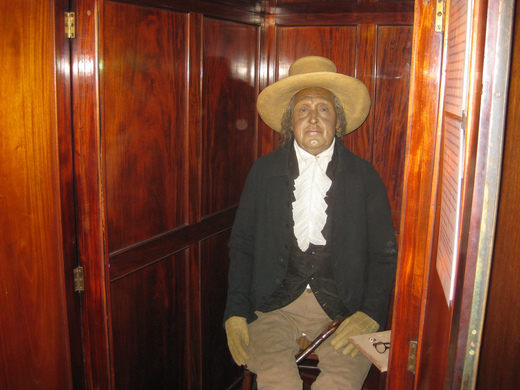

As he lay dying in the spring of 1832, the great philosopher Jeremy Bentham left detailed directions for the preservation of his corpse. First, it was to be publicly dissected in front of an invited audience. Then, the preserved head and skeleton were to be reassembled, clothed, and displayed ‘in the attitude in which I am sitting when engaged in thought and writing.’ His desire to be preserved forever was a political statement. As the foremost secular thinker of his time, he wanted to use his body, as he had his mind, to defy religious superstitions and advance real, scientific knowledge. Almost 200 years later, Bentham’s ‘auto-icon’ still sits, staring off into space, in the cloisters of University College London.

His full-body parody of saints’ relics doesn’t just sit in London, in the “appropriate box or case” he specified in his instructions. It has also sat in its box in cities across England, Germany, and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Not unlike an aging British rock star,” writes Isaac Schultz at Atlas Obscura, “the older he gets, the more tours he seems to go on. Sometimes Bentham’s severed, mummified head,” with its terrifying, unblinking glass eyes, “accompanies the rest of him.” Sometimes it doesn’t.

The head, which was supposed to have been kept atop the fully dressed skeleton, was mishandled and damaged in the creation of the “auto-icon” and replaced by a wax replica (surely an accident and not a way to mitigate the creepiness). What did Bentham mean by all of this? And what is an “auto-icon”? Though it sounds like the sort of inscrutable prank Salvador Dali might have played at the end, Bentham described the idea straightforwardly in his pamphlet Auto-Icon; or, Farther Uses of the Dead to the Living. The philosopher, says Hannah Cornish, science curator at the University College London, genuinely “thought it’d catch on.”

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

In his short, final work of moral philosophy, Bentham shows that, like Plato, he didn’t quite get the point of making art, advancing a theory that becoming one’s own icon would eliminate the need for paintings, statues, and the like, since “identity is preferable to similitude” (to the extent that a mummified corpse is identical to a living person). Other utilitarian reasons include benefits to science, reduced public health risks, and creating “agreeable associations with death.”

Also, in what must have been intended with at least some undercurrent of humor, he asked that his remains “occasionally be brought into meetings involving his still-living friends,” writes Schultz, “so that what’s left of Bentham might enjoy their company.”

Learn more about Bentham’s “auto-icon” in the Atlas Obscura videos here, including the video further up showing how a team of professionals packed up and moved the whole macabre assemblage to its new home across the University of London campus. And read an even more detailed description, with several photographs, of how the oldest partially mummified British rock star philosopher travels, here.

Related Content:

97-Year-Old Philosopher Ponders the Meaning of Life: “What Is the Point of It All?”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

What’s the point of it all?