It’s not especially hard to get inexpensive tickets to the opera if you live in, say, New York. But it’s not so easy if you live hundreds of miles from a major opera house. Opera’s rarity, however, does not make it a “more elevated” form than, say, musical theater, argues Anthony Tommasini in The New York Times. Musicals may have market share, and opera may barely sustain itself from a dwindling pool of private donors, but the comic operas of Mozart once played broadly to mass audiences, “and there is no bigger crowd pleaser than Leoncavallo’s impassioned ‘Pagliacci.’”

The major formal difference between musical theater and opera is that “in opera, music is the driving force; in musical theater, words come first. This explains why for centuries opera-goers have revered works written in languages they do not speak,” even in a time before supertitles. “As long as you basically know what is going on and what is more or less being said, you can be swept away by a great opera, not just by music, but by visceral drama.” In order for that to happen, you’ll need to see and hear much more than highlights and greatest hits. And a little bit of context goes a long way.

If you don’t live in a major city or can’t get to the opera often, you can watch full-length performances online at projects like The Opera Platform, which not only includes filmed popular operas like Verdi’s La Traviata, but also, as Colin Marshall noted in an earlier Open Culture post, “provides a host of supplementary materials, including documentary and historical materials that put the month’s featured opera in context.” If you’re ready to dig deeper, however, or are already a scholar of the form, or if you, yourself, happen to be an opera singer, then you will absolutely want to visit the Opera Database.

The archival resource describes its purpose as threefold:

- To create a comprehensive database of operas.

- To catalog arias and create PDFs from Public Domain sources, for the purpose of broadening the opera singer’s audition repertoire and seeking out rarely heard pieces.

- To create a repository for operatic information, including libretti, scores, and synopses.

The dropdown menus on the homepage’s search field alone give you a sense of how expansive the database is—with dozens of languages, from Arabic and Azerbaijani to Uzbek and Vietnamese, dozens of nationalities, and thousands of entries from over four centuries. Most of these works will be unknown even to lifelong opera lovers who have only listened to the European classics. And several famous modern composers, like John Adams of Nixon in China fame, have shown how relevant the form still is for contemporary concerns and costumes.

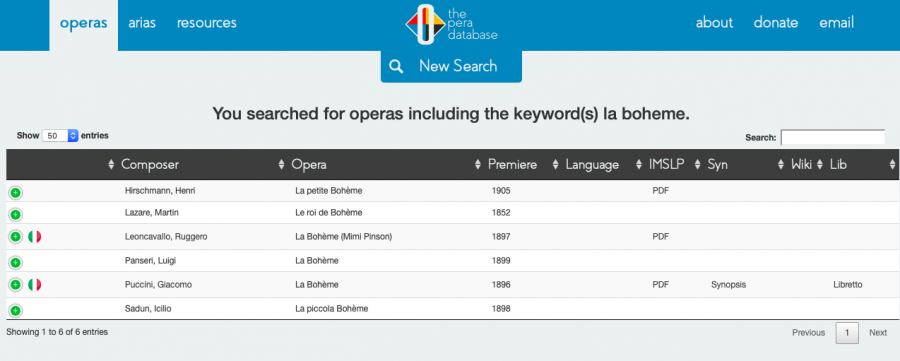

All that said, only a portion of the entries have links to synopses and libretti. Search major titles like Nixon in China or Puccini’s La boheme and you’ll find pdf scores and libretti translated into several languages. Search anything more obscure than these blockbusters and you’ll only turn up the most basic information on the composer, nationality, and year of composition. Nonetheless the Opera Database has something for everyone, from the opera-curious to the opera-adept, with a separate aria database that allows users to search voice types from bass to soprano in twelve languages.

Whether you’re looking to expand your knowledge beyond “kill the wabbit” parodies or expand your already advanced repertoire of material, you’ll find this online opera catalogue offers a wealth of information for better understanding an emotionally engaging, if endangered, cultural form.

via Nicola Freddo

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply