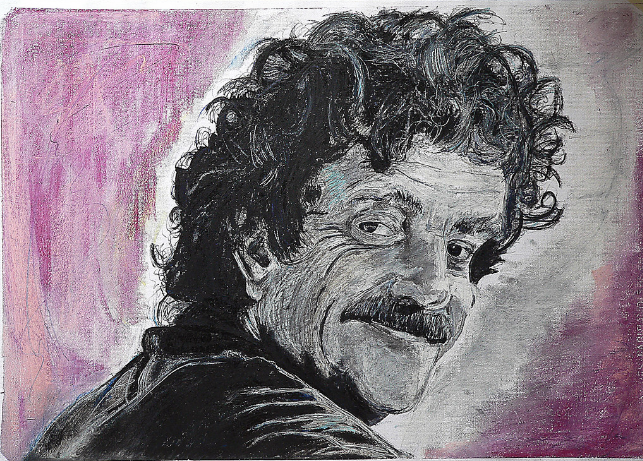

Image by Daniele Prati, via Flickr Commons

Kurt Vonnegut has been gone a dozen years now, but in that time his stock in the world of American literature has only risen. Just a few months ago we featured the newly opened Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library here on Open Culture, and we’ve also posted about everything from his writing tips to his letters to his drawings. And we’ve featured his conception of “the shape of all stories” as originally laid out in his master’s thesis at the University of Chicago, where between 1945 and 1947 he performed anthropological research into the Native American-inspired Ghost Dance religious movement of the late 19th century. “The fundamental idea,” wrote Vonnegut, “is that stories have shapes which can be drawn on graph paper, and that the shape of a given society’s stories is at least as interesting as the shape of its pots or spearheads.”

None of this flew with the anthropology department. In an essay in his book Palm Sunday Vonnegut explains the unanimous rejection of his thesis, “The Fluctuations Between Good and Evil in Simple Tasks,” due to the fact that “it was so simple and looked like too much fun. One must not be too playful.” Opting not to have a second go before the committee, the still-young Vonnegut — with his harrowing experience in the Second World War only a couple of years behind him — decided to take a job as a publicist at General Electric instead. In 1950, while still employed at GE, he would first publish a piece of fiction: “Report on the Barnhouse Effect” in Collier’s magazine. “Years later,” says the University of Chicago Chronicle’s obituary for Vonnegut, “the university accepted Cat’s Cradle as Vonnegut’s thesis, awarding him an A.M. in 1971.”

“This was not an honorary degree but an earned one,” said Vonnegut in a 1973 interview, “given on the basis of what the faculty committee called the anthropological value of my novels. I snapped it up most cheerfully and I continue to have nothing but friendly feelings for the University.” Indeed, Vonnegut called his time as a Phoenix “the most stimulating years of my life.” Generations of readers have found in Vonnegut’s work — not just Cat’s Cradle, the one that finally got him his academic credentials, but other novels like Mother Night, Breakfast of Champions, and of course Slaughterhouse-Five as well — some of the most stimulating writing to come out of postwar America. And yet Vonnegut, as he writes in Palm Sunday, continued to regard his first master’s thesis as “my prettiest contribution to my culture.” The more successful the creator, it can often seem, the more dear he holds his failures.

Related Content:

Kurt Vonnegut Diagrams the Shape of All Stories in a Master’s Thesis Rejected by U. Chicago

Kurt Vonnegut: Where Do I Get My Ideas From? My Disgust with Civilization

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

How can we read the MA thesis?

I had drinks one night in the late 1990s with one of the anthropology professors on the committee (whose name I no longer remember)that rejected Vonnegut’s thesis. We both had one to many and he opened up about being on the committee that rejected Vonnegut’s theisis. I find the above article an interesting spin at rewriting history.

Ed,

Would you care to set the record straight and tell us the real reason why the committee rejected the thesis?

We are all ears.

OC

If you are a graduate of the University of Chicago, you are considered a “Maroon.” Not a Phoenix.

We probably can’t, I am currently trying to locate it and this is all I found.

“Kurt’s papers were donated to Indiana University’s library. You can browse what’s in the collection online, but I don’t believe that any of the papers are available digitally right now.” http://www.indiana.edu/~liblilly/lilly/mss/index.php?p=vonnegutinv&i=4