Every living adult has witnessed enough technological advancement in their lifetime to marvel at just how much has changed, and digital streaming and telecommunications happen to be areas where the most revolutionary change seems to have taken place. We take for granted that the present resembles the past not at all, and that the future will look unimaginably different. So the narrative of linear progress tells us. But that story is never as triumphantly simple as it seems.

In one salient counterexample, we find that not only did livestreaming music and news exist in theory long before the internet, but it existed in actual practice—at the very dawn of recording technology, telephony, and general electrification. First developed in France in 1881 by inventor Clement Ader, who called his system the Théâtrophone, the device allowed users to experience “the transmission of music and other entertainment over a telephone line,” notes the site Bob’s Old Phones, “using very sensitive microphones of [Ader’s] own invention and his own receivers.”

The pre-radio technology was ahead of its time in many ways, as Michael Dervan explains at The Irish Times. The Théâtrophone “could transmit two-channel, multi-microphone relays of theatre and opera over phone lines for listening on headphones. The use of different signals for the two ears created a stereo effect.” Users subscribed to the service, and it proved popular enough to receive an entry in the 1889 edition of The Electrical Engineer reference guide, which defined it as “a telephone by which one can have soupçons of theatrical declamation for half a franc.”

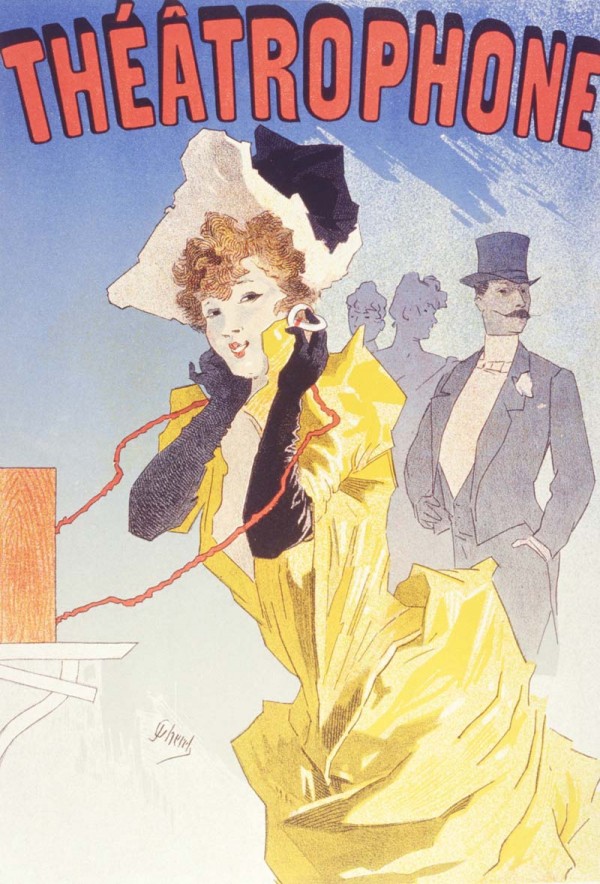

In 1896 “the Belle Epoque pop artist Jules Cheret immortalized the theatrophone,” writes Tanya Basu at Mental Floss, “in a lithograph featuring a woman in a yellow dress, grinning as she presumably listened to an opera feed.” Victor Hugo got to try it out. “It’s very strange,” he wrote. “It starts with two ear muffs on the wall, and we hear the opera; we change earmuffs and hear the French Theatre, Coquelin. And we change again and hear the Opera Comique. The children and I were delighted.”

Though The Electrical Engineer also called it “the latest thing to catch [Parisians’] ears and their centimes,” the innovation had already by that time spread elsewhere in Europe. Inventor Tivador Puskas created a “streaming” system in Budapest called Telefon Hermondo (Telephone Herald), Bob’s Old Phones points out, “which broadcast news and stock market information over telephone lines.” Unlike Ader’s system, subscribers could “call in to the telephone switchboard and be connected to the broadcast of their choice. The system was quite successful and was widely reported overseas.”

The mechanism was, of course, quite different from digital streaming, and quite limited by our standards, but the basic delivery system was similar enough. A third such service worked a little differently. The Electrophone system, formed in London in 1884, combined its predecessors’ ideas: broadcasting both news and musical entertainment. Playback options were expanded, with both headphones and a speaker-like megaphone attachment.

Additionally, users had a microphone so that they could “talk to the Central Office and request different programs.” The addition of interactivity came at a premium. “The Electrophone service was expensive,” writes Dervan, “£5 a year at a time when that sum would have covered a couple months rent.” Additionally, “the experience was communal rather than solitary.” Subscribers would gather in groups to listen, and “some of the photographs” of these sessions resemble “images of addicts in an old-style opium den”—or of Victorians gathered at a séance.

The company later gave recuperating WWI servicemen access to the service, which heightened its profile. But these early livestreaming services—if we may so call them—were not commercially viable, and “radio killed the venture off in the 1920s” with its universal accessibility and appeal to advertisers and governments. This seeming evolutionary dead end might have been a distant ancestor of streaming live concerts and events, though no one could have foreseen it at the time. No one save science fiction writers.

Edward Bellamy’s 1888 utopian novel Looking Backward imagined a device very like the Théâtrophone in his vision of the year 2000. And in 1909, E.M. Forster drew on early streaming services and other early telecommunications advances for his visionary short story “The Machine Stops,” which extrapolated the more isolating tendencies of the technology to predict, as playwright Neil Duffield remarks, “the internet in the days before even radio was a mass medium.”

Related Content:

The History of the Internet in 8 Minutes

Hear the First Recording of the Human Voice (1860)

How an 18th-Century Monk Invented the First Electronic Instrument

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply