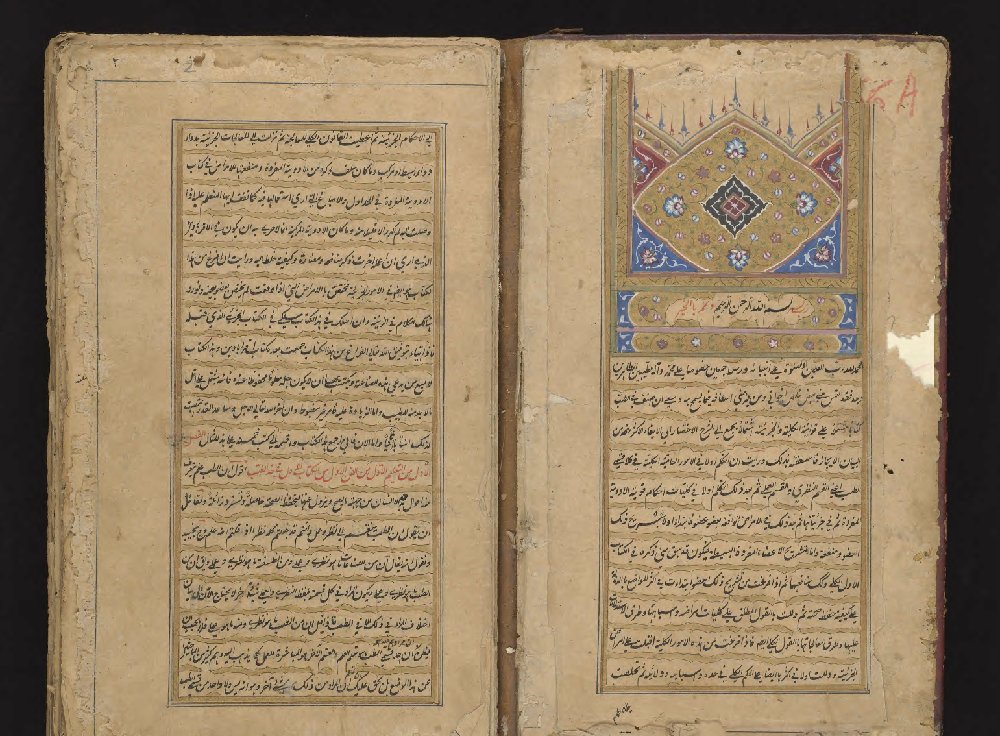

It may never lend a catchy title to a steamy TV hospital drama, but Avicenna’s 11th-century Canon of Medicine has the distinction of being “the most famous medical textbook ever written.” It has remained, as William Osler wrote in a 1918 Yale lecture, “a medical bible for a longer time than any other work.” Completed in 1025, the compendium drew Greek, Roman, Arabic, Indian, and Chinese medical science together in five dense volumes of material informed by the theories of Galen and structured by the systematic philosophy of Aristotle, whom Avicenna (Abū-ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn-ʿAbdallāh Ibn-Sīnā) called “The First Teacher.”

Translated into Latin in the 12th century and “often revised,” the Canon, notes the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “formed the basis of medical instruction in European Universities until the 17th century.” A copy of excerpts from the text has even been found translated into 15th-century Irish, demonstrating a link between medieval Ireland and the Islamic world. Avicenna’s influence generally on the intellectual culture of medieval and early modern Europe and the Arab-speaking world can hardly be overstated.

Born in 980 A.D., the Persian philosopher and physician was instrumental in the recovery of Hellenic thought, first in the Islamic world, then later in Europe. He took to the study of medicine very early in his extraordinary career. “I became proficient in it in the shortest time,” he says, “until the excellent scholars of medicine began to study under me.” He also became a practicing physician, inspired by a desire to put his learning to the test. “Through my experiences I acquired an amazing practical knowledge and ability in methods of treatment.”

The practical knowledge in The Canon of Medicine was largely the basis for its continued use for centuries. It lays out rules for drug testing, which include an insistence on human trials and the importance of conducting multiple experiments and showing consistent results across cases. Like most classical scientific texts, it weaves empirical observation with metaphysics, theology, scholastic speculation, and cultural biases particular to its time and place. But the practical outlines of its medical knowledge transcend its archaisms.

The work presents “an integrated view of surgery and medicine,” notes the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. In addition to his imminently useful guide for assessing the effects of drugs, Ibn Sina tells his readers “how to judge the margin of healthy tissue to remove with an amputation,” an intervention that has saved countless numbers of lives. “The enduring respect in the 21st century for a book written a millennium earlier is testimony to Ibn Sina’s achievement.”

One of the defining features of the text is its insistence on the practice of medicine as a systematic scientific pursuit of equal merit to the theorizing of it:

Someone might say to us that medicine is divided into theoretical and practical parts and that, by calling it a science, we have considered it as being all theoretical. To this we respond by saying that some arts and philosophy have theoretical and practical parts, and medicine, too, has its theoretical and practical parts. The division into theoretical and practical parts differs from case to case, but we need not discuss these divisions in disciplines other than medicine. If it is said that some parts of medicine are theoretical and other parts are practical, this does not mean that one part teaches medicine and the other puts it into practice – as many researchers in this subject believe. One should be aware that the intention is something else: it is that both parts of medicine are science, but one part is the science dealing with the principles of medicine, and the other with how to put those principles into practice.

Of course, much of the medical theory in the Canon has been disproven, but it remains of keen interest to students of the history of medicine and of European and Islamic intellectual cultural history more generally. Avicenna towers above his contemporaries, yet his work also bears witness to the larger “intellectual climate of his time,” as the site Medical History Tour points out. He emerged from a milieu “shaped by centuries of translation and cross-cultural scholarship” of Greek, Roman, Indian, Chinese, Persian, and Arabic literature. “A rich Persian medical tradition began 200 years before Avicenna.”

Nonetheless, “however the world came by the genius of Avicenna, his influence was lasting,” with The Canon of Medicine remaining a definitive “best practices” guide to medicine for centuries after its composition. See full scans of several Arabic copies of the text at the Library of Congress’s World Digital Library and read a full English translation of the massive 5‑volume work, with its extensive chapters on definitions, anatomy, etiology, and treatments, at the Internet Archive.

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

700 Years of Persian Manuscripts Now Digitized and Available Online

How Arabic Translators Helped Preserve Greek Philosophy … and the Classical Tradition

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

medicines knowledge