Robert Graves’ poem “Armistice Day, 1918” begins with a riot of sound in a town in North East England. “What’s all this hubbub and yelling, / Commotion and scamper of feet,” he writes, “With ear-splitting clatter of kettles and cans, / Wild laughter down Mafeking Street?” The poem grows somber, then embittered, ending in a chilling silence for the “boys who were killed in the trenches, / Who fought with no rage and no rant.” It’s a familiar contrast from much World War I poetry—the hooting civilian crowds and the grim, silent soldiers counting their losses.

One project, created as part of the 100th anniversary of the Armistice last year, gave us a different take on this WWI theme of sound and silence —using innovative techniques from 1918 that turned the final shelling of the war into visual data, then translating that data back into sound a century later. Rather than celebration, the “ear-splitting clatter” is the sound of mass death, and the silence, though surely “uneasy,” as Matt Novak writes, must also have been revelatory.

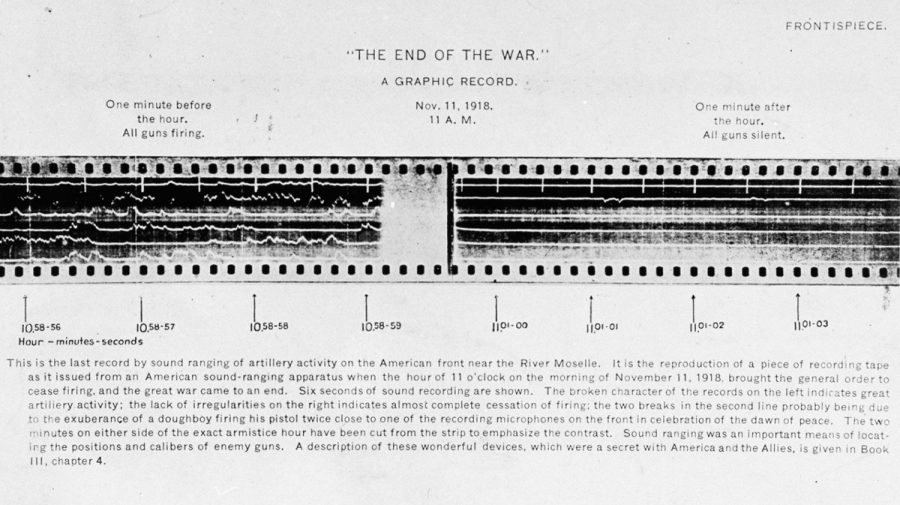

In the “graphic record” of the Armistice, just below, we can “see” the deafening sounds of war and the first three silent seconds of its end, at 11 A.M. November 11th, 1918. The film strip records six seconds of vibration from six different sources, as the graphic, from the Army Corps of Engineers, informs us. “The broken character of the records on the left indicates great artillery activity; the lack of irregularities on the right indicates almost complete cessation of firing.”

You might notice a couple little breaks in one line on the right—likely the result of an exuberant “doughboy firing his pistol twice close to one of the recording microphones on the front in celebration of the dawn of peace.” But this was 1918—field recording technology barely existed, though a few battlefield attempts were made (at least one survives). The “microphones” in question were actually “barrels of oil dug into the ground,” notes Jason Daley at Smithsonian.

This technique, called “sound ranging,” worked by registering vibration, similar to a seismograph’s operation, and helped special units locate enemy fire, using “photographic film to visually record noise intensity.” The film above was part of the centenary exhibition at London’s Imperial War Museum, which also commissioned sound designers Coda to Coda to reconstruct the dramatic moment with an audio interpretation. At the top of the post, hear what the seconds before and after the Armistice likely sounded like, as recorded on the American front at the River Moselle.

Listening to the seconds of the war’s end from the battlefield perspective—rather than streets filled with cheering crowds—is rather chilling, “a sudden reprieve from the staccato of weapons blasting,” Novak writes. The “graphic record” of the Armistice also shows us “just how horrifically precise and cruel war can be.” The slaughter could have been stopped in an instant, by the mutual decree of world leaders, at maybe any time during those harrowing four years.

On November 11 at 11 A.M., “the guns fell silent,” writes the Imperial War Museum, and “a new world began.” But as artists like Graves remind us, for the returning maimed and traumatized soldiers and the hundreds of thousands of bereaved families, the war didn’t end when the noise finally stopped.

Related Content:

Watch World War I Unfold in a 6 Minute Time-Lapse Film: Every Day From 1914 to 1918

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply