There was a time—a strange time in pop culture history, I’ll grant—when legal dramas were everywhere in television, popular fiction, and film. Next to the barn-burning courtroom set pieces in A Few Good Men and A Time to Kill, for example, scenes of lawyers poring over case law with loosened ties, high heels kicked off, and martinis and scotches in hand were rendered with maximum dramatic tension, despite the fact that case law is a nigh unreadable jumble of jargon, citations, archaic diction and syntax, etc… anything but brimming with cinematic potential.

Do law students and legal scholars disagree with this assessment? It’s beside the point, many might say. The centuries-old web of case law—reinforcing, contradicting, overturning, creating patterns and structures—is the very stuff the law is made of.

It’s a referential tradition, and when most of the documents are in the hands of only a few people, only those people understand why the law works the way it does. The rest of us are left to wonder why the legal system is so Byzantine and incomprehensible. Real life rarely has the clarity of a satisfying courtroom drama.

Last year, The Harvard Crimson reported a seemingly revolutionary shift in that dynamic, when Harvard Law’s Caselaw Access Project “digitized more than 40 million pages of U.S. state, federal, and territorial case law documents from the Law School library,” dating back to 1658. The Crimson issued one caveat: the full database is accessible to the public, but “users are limited to five hundred full case texts per day.” Plan your intense, scotch-soaked all-nighters accordingly.

Is this altruism, civic duty, a move in the right direction of freeing publicly funded research for public use? Several Harvard Law faculty have said as much. “Case law is the product of public resources poured into our court system,” writes Professor I. Glenn Cohen. “It’s great that the public will now have better access to it.” It is indeed, Professor Christopher T. Bavitz says: “If we want to ensure that people have access to justice, that means that we have to ensure that they have access to cases. The text of cases is the law.”

The law is not a set of abstract principles, theories, or rules, in other words, but a series of historical examples, woven together into a social narrative. Machines can analyze data from The Caselaw Access Project far faster and more efficiently than any human, giving us broader views of legal history and precedent, and greatly expanding public understanding of the system. Harvard’s Library Innovation Lab has itself already created several apps for just this purpose.

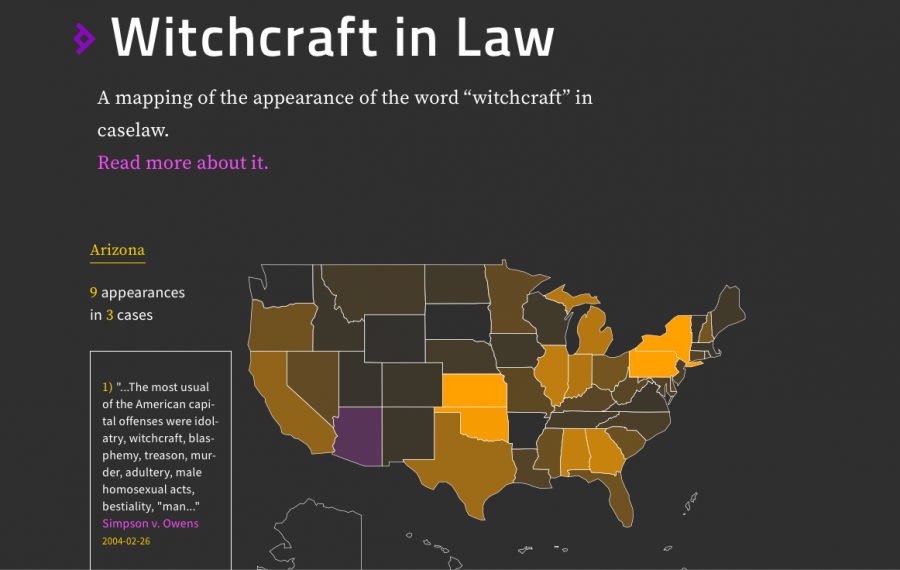

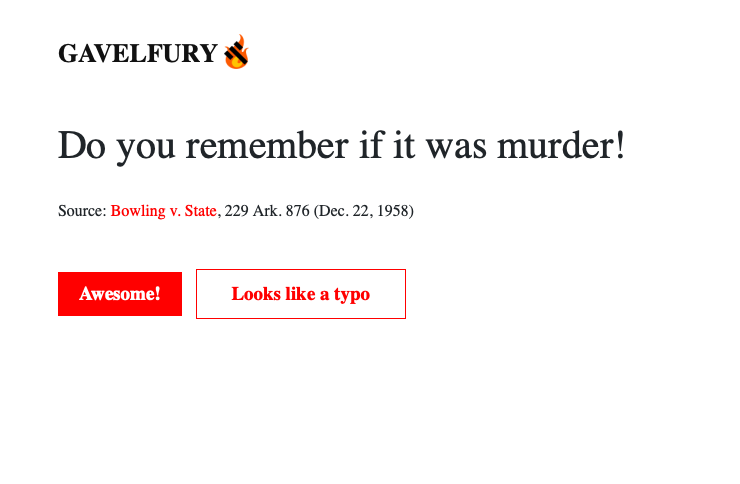

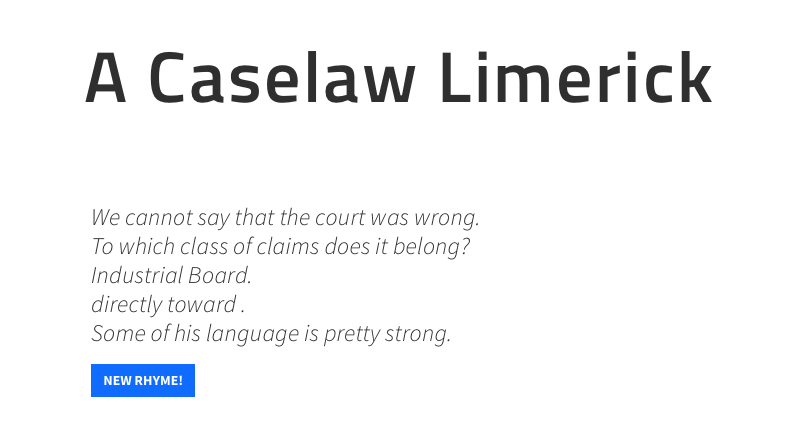

There’s California Wordclouds, which shows the most-used words in California caselaw between 1852 and 2015, and Witchcraft in Caselaw, which does what it says, with an interactive map of all appearances of witchcraft in cases across the country. There’s “Fun Stuff” too, like a Caselaw Limerick Generator, a visual database that analyzes colors in case law, and “Gavelfury,” which analyzes “all instances of ‘!,’” giving us gems like “Do you remember if it was murder!” from Bowling v. State, 229 Ark. 876 (Dec. 22, 1958).

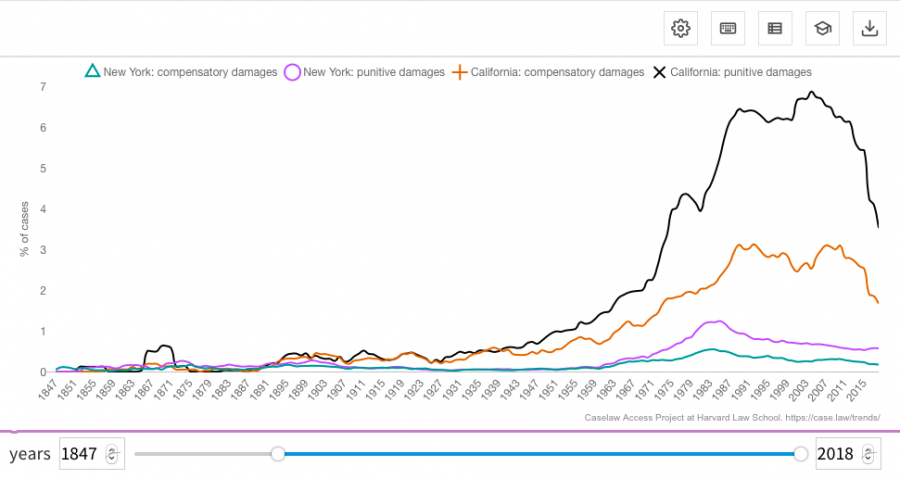

One new graphing tool, Historical Trends, announced in June, makes it easy for users to “visualize word usage in court opinions over time,” writes the Library Innovation Lab. (Examples include comparing the “frequency of ‘compensatory damages’ and ‘punitive damages’ in New York and California” and comparing “privacy” with “publicity.”) Anyone can build their own data visualization using their own search terms. (Learn how and get started here.) Case law may never be glamorous, exactly, or fun to read, but it may be far more interesting, and empowering, than we imagine.

Be aware that the Caselaw Access Project could still find ways to restrict or monetize access, for a short time, at least. “The project was funded partly through a partnership with Ravel, a legal analytics startup founded by two Stanford Law School students,” reports the Crimson. The company “earned ‘some commercial rights’ through March 2024 to charge for greater access to files.” The startup has issued no word on whether this will happen. In the meantime, public interest legal scholars may wish to do their own digging through this trove of caselaw to better understand the public’s right to information of all kinds.

Related Content:

Bound by Law?: Free Comic Book Explains How Copyright Complicates Art

Positive Psychology: A Free Course from Harvard University

Harvard Launches a Free Online Course to Promote Religious Tolerance & Understanding

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply