How times have changed since our late 80s college days. Undergrads do research online, upload assignments to a server, stream music, download affirmative sexual consent contracts, and turn to Facebook when it’s time to find a ride home for the holidays.

But one aspect of the collegiate lifestyle remains unchanged.

They still festoon their dorm rooms with posters—the actual paper article, affixed to the walls with blue putty, a carefully curated collection of taste and aspiration.

As Cait Munro writes in Refinery 29:

Freshman, already scrambling to find and loudly articulate an identity, can leave the poster sale with two or three plastic tubes housing scrolls that represent the very essence of their new, parent-free, on-campus selves. Posters become an affordable, demonstrable expression of who they are as a person — or, in the tradition of people eager to leave behind their hometown selves, who they want to be.

Legions of style blogs have decreed that these posters should be given the heave-ho along with the plastic milk crate shelving, come graduation.

Personally, I would rather gaze upon the tattered reproduction of the first painting that spoke to me at the Art Institute of Chicago than anything the design experts float as an acceptably grown up alternative.

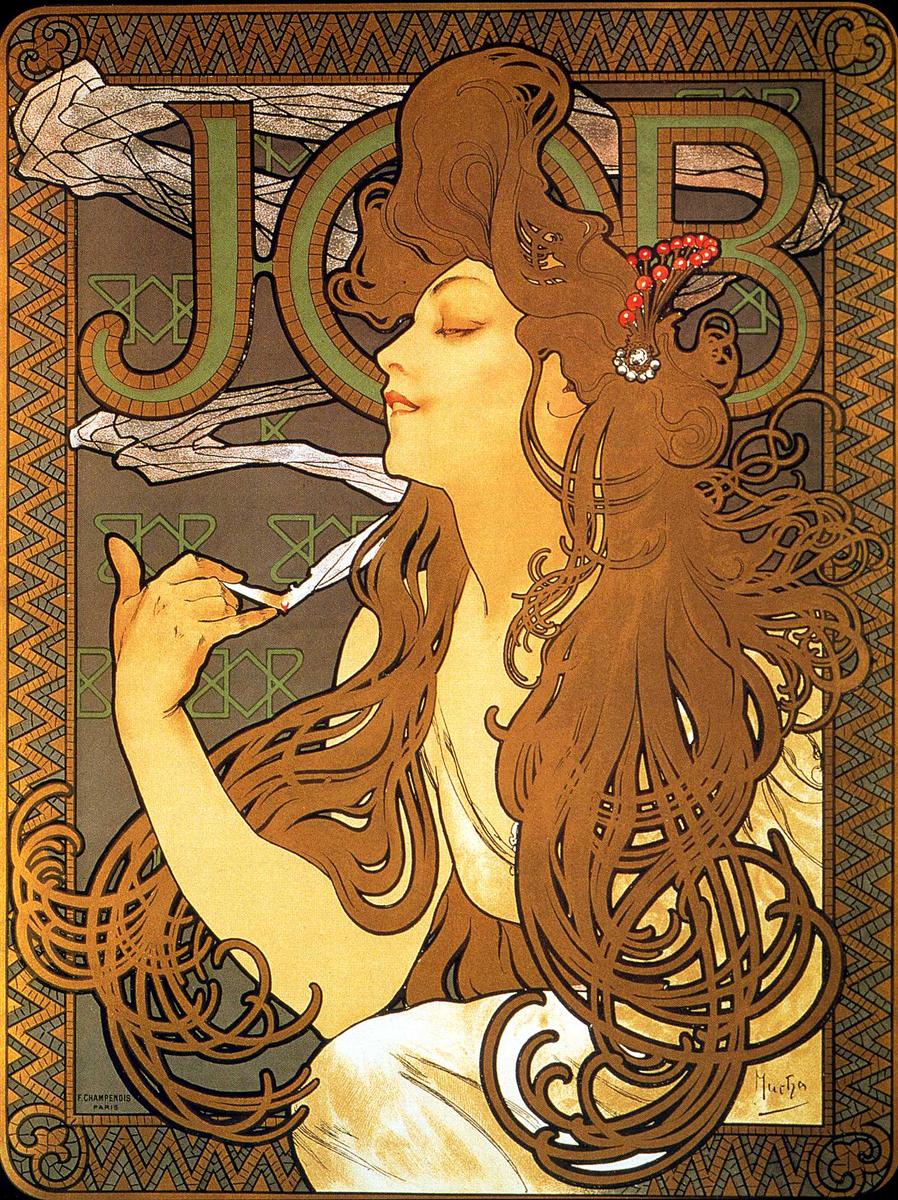

Is Alphonse Mucha’s Byzantine 1896 ad for Job rolling papers somehow unworthy because legions of dewy eyed undergrads have given it a perennial place of unframed honor?

The driving forces behind the newly opened Poster House in New York City would say no. The first American museum dedicated exclusively to poster art, its curators cast a wide net through the form’s 160 year history, whether the end goal of the work was war bond sales, public health education, or straight-up box office sales. As the Poster House writes:

For a poster to succeed, it must communicate. By combining the power of images and words, posters speak to audiences quickly and persuasively. Blending design, advertising, and art, posters clearly reflect the place and time in which they were made.

What did the best-selling poster of actress Farrah Fawcett in a red tank suit say to—and about—teenage boys in 1976? What did it say about American values and gender norms in that Bicentennial year? Why no posters of Betsy Ross?

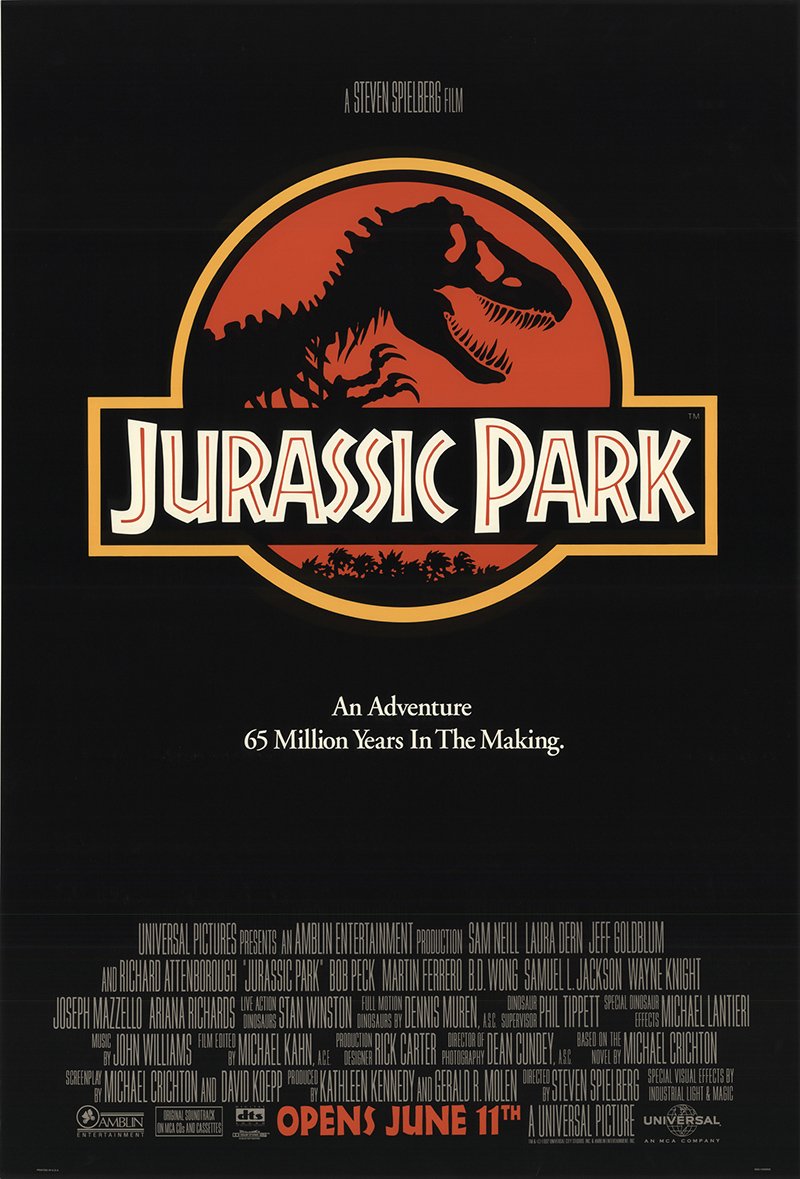

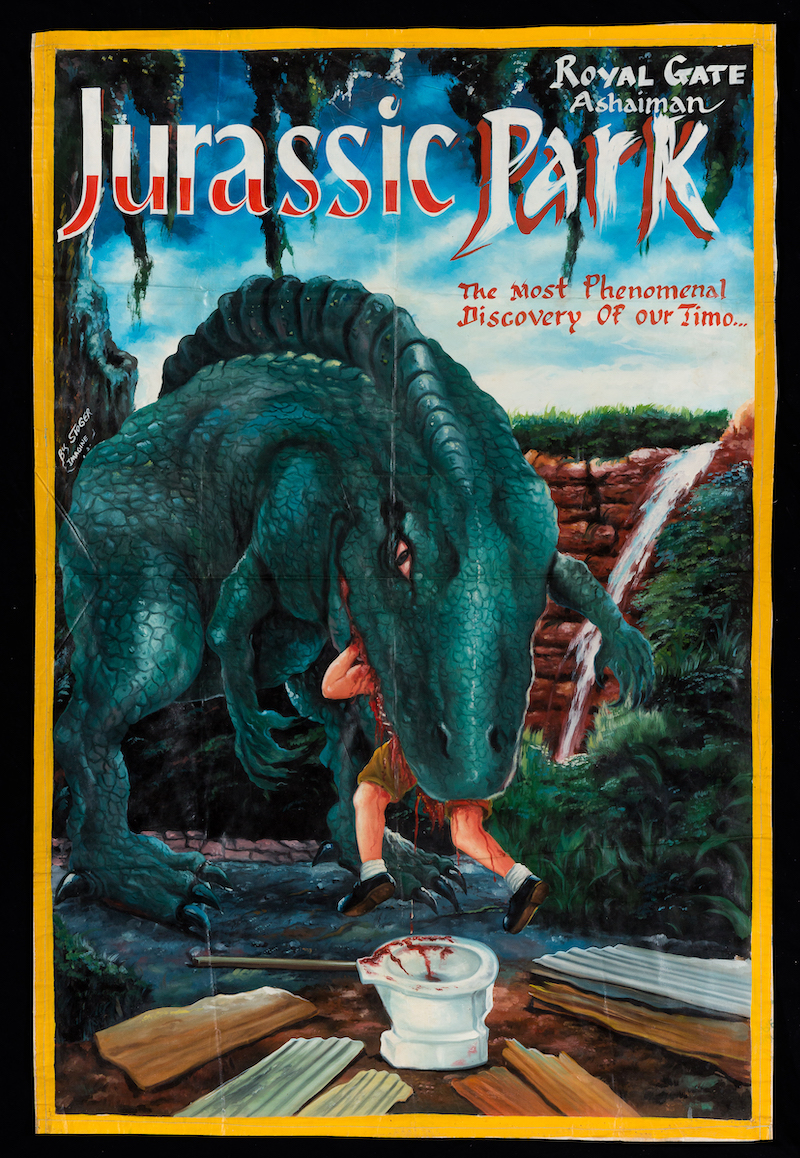

How does the official poster for Jurassic Park, above, compare to the hand-painted, presumably unauthorized image used to market it to audiences in Ghana?

(Endless gratitude to illustrator and monster movie fan Aeron Alfrey for bringing this and other Ghanian spins on American film releases to our attention.)

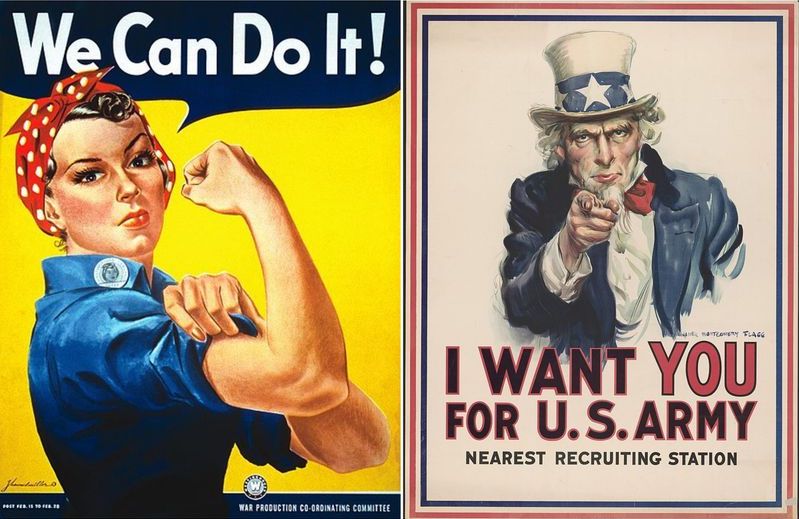

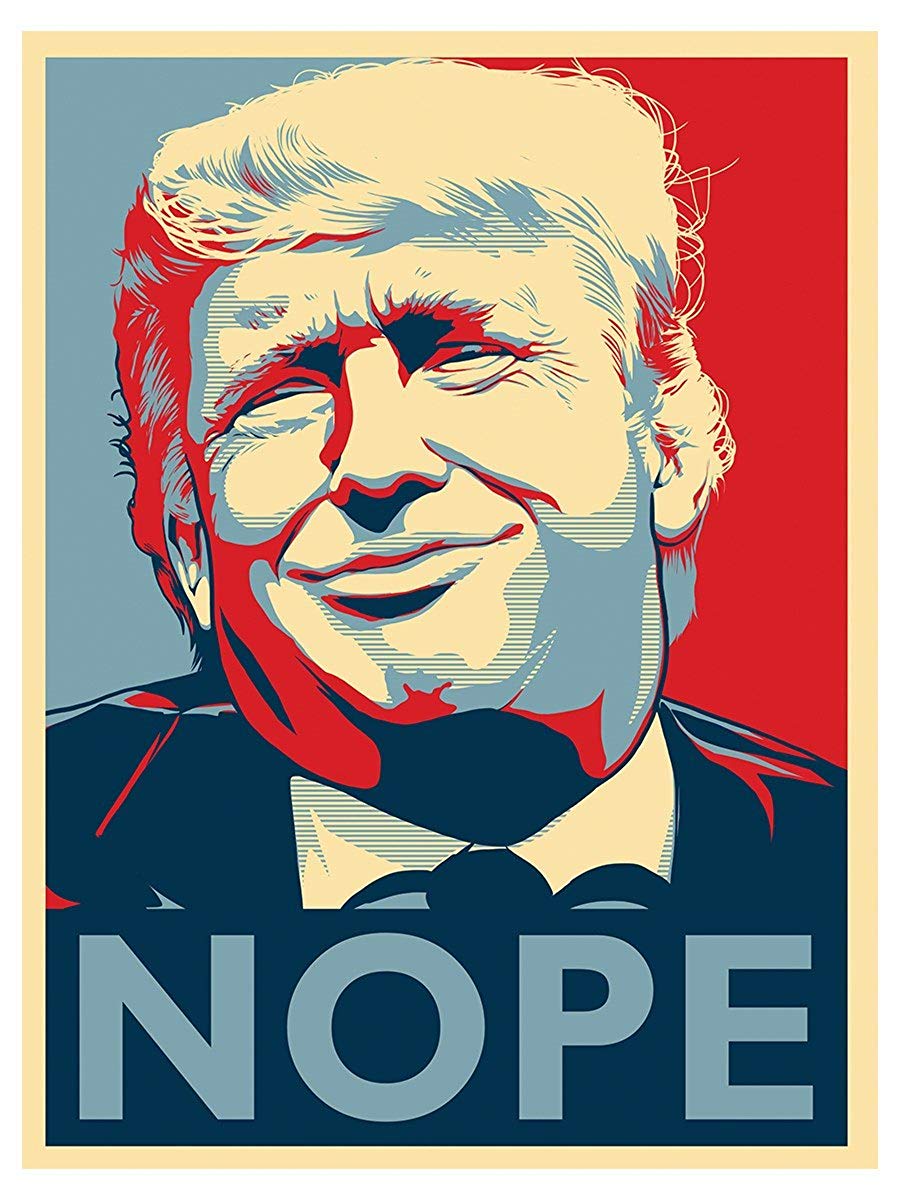

Some posters have remarkable staying power, reappearing in a number of guises. Witness Rosie the Riveter and James Montgomery Flagg’s Uncle Sam-themed WWI recruitment poster, to say nothing of the Barack Obama “Hope” poster by Shepard Fairey, the poster that launched a thousand parodies, mostly digital, but even so.

To learn more about visiting Poster House, its inaugural Alphonse Mucha exhibit and upcoming events such as Drink and Draw, click here.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

The Film Posters of the Russian Avant-Garde

Chilling and Surreal Propaganda Posters from the NSA Are Now Declassified and Put Online

Vintage 1930s Japanese Posters Artistically Market the Wonders of Travel

100 Greatest Posters of Film Noir

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

This is good to see. Poster Art has a long history and is a comprehensive documenter of human culture at specific times and places. As a body of work it records and documents, many times being the median where early signals of the future can be found. I think this has been a popular yet under estimated art form both of the quality of the work and its ability to capture what often is fleeting or mixed.