Photo by Mathias Schindler, via Wikimedia Commons

Drawn from Aristotle and his Roman and Medieval interpreters, the “classical trivium”—a division of thought and writing into Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric—assumes at least three things: that it matters how we arrive at our ideas, it matters how we express them, and it matters how we treat the people with whom we interact, even, and especially, those with whom we disagree. The word rhetoric has taken on the connotation of empty, false, or flattering speech. But it originally meant something closer to kindness.

We might note that this pedagogy comes from a logocentric tradition, one that privileges writing over oral communication. But while it ignores physical niceties like gesture, posture, and personal space, we can still incorporate its lessons into spoken conversation—that is, if we’re interested in having constructive dialogue, in being heard, finding agreement, and learning something new. If we want to lob shots into the abyss and hear hundreds of voices echo back, well… this requires no special consideration.

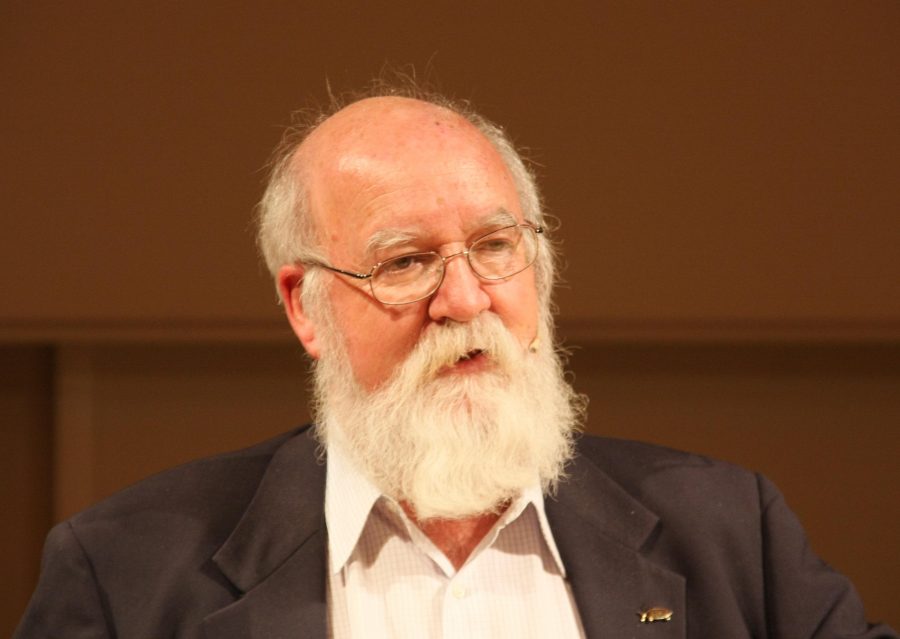

The subject of sound rhetoric—with its subsets of ethical and emotional sensitivity—has been taken up by philosophers over hundreds of years, from medieval theologians to the staunchly atheist philosopher of consciousness Daniel Dennett. In his book Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking, Dennett summarizes the central rhetorical principle of charity, calling it “Rapoport’s Rules” after an elaboration by social psychologist and game theorist Anatol Rapoport.

Like their classical predecessors, these rules directly tie careful, generous listening to sound argumentation. We cannot say we have understood an argument unless we’ve actually heard its nuances, can summarize it for others, and can grant its merits and concede it strengths. Only then, writes Dennett, are we equipped to compose a “successful critical commentary” of another’s position. Dennett outlines the process in four steps:

- Attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly and fairly that your target says: “Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way.”

- List any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement).

- Mention anything you have learned from your target.

- Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism.

Here we have a strategy that pays dividends, if undertaken in the right spirit. By showing that we understand an opponent’s positions “as well as they do,” writes Dennett, and that we can participate in a shared ethos by finding points of agreement, we have earned the respect of a “receptive audience.” Alienating people will end an argument before it even begins, when they turn their backs and walk away rather than subject themselves to obtuseness and abuse.

Additionally, making every effort to understand an opposing position will only help us better consider and present our own case, if it doesn’t succeed in changing our minds (though that danger is always there). These are remedies for better social cohesion and less shouty polarization, for deploying “the artillery of our righteousness from behind the comfortable shield of the keyboard,” as Maria Popova writes at Brain Pickings, “which is really a menace of reacting rather than responding.”

Yelling, or typing, into the void, rather than engaging in substantive, respectful discussion is also a terrible waste of our time—a distraction from much worthier pursuits. We can and should, argues Dennett, Rapoport, and philosophers over the centuries, seek out positions we disagree with. In seeking out and trying to understand their best possible versions, we stand to gain new knowledge and widen our appreciation.

As Dennett puts it, “when you want to criticize a field, a genre, a discipline, an art form… don’t waste your time and ours hooting at the crap! Go after the good stuff or leave it alone.” In “going after the good stuff,” we might find that it’s better, or at least different, than we thought, and that we’re wiser for having taken the time to learn it, even if only to point out why we think it mostly wrong.

via Brain Pickings/Boing Boing

Related Content:

Daniel Dennett Presents Seven Tools For Critical Thinking

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I just recently discovered Dan via an article in an old New Yorker (a neighbour had put out a cubic foot of them for pickup by passersby). Of course I gained only a nodding acquaintance with his ideas but I thought he might enjoy a metaphor that has come to me: the mind/brain/whatever is the kitchen of behaviour, and consciousness is the kitchen smells — something that just arises when a certain threshold is crossed during a certain kind of “cooking”.

I studied philosophy and psychology for my BA, back in the 1960s, and cooking is one of my principal hobbies. I also share Dan’s love of a good tune — one of my favourites is Winchester New, a hymn tune that goes back to 1690.

Ruth von Fuchs

Good advices, but hard to follow them. Especially when your interlocutor is not very smart.