In the mid-seventies, many people felt excluded from and disdained by the mainstream of rock and roll, which had largely come to represent itself as a straight white boys and girls club full of superrich rock stars. The narrow image fostered attitudes of implicit racism and homophobia that exploded in the 1979 “Disco Sucks” backlash. This despite the fact that rock and roll began as interracial music built on the flamboyantly ambiguous sexuality of Little Richard, the racy short stories of Chuck Berry, the grooves of Chubby Checker, the edgy beats of Bo Diddley, and a great many unsung black female performers.

Now we tend to remember 70s rock differently, not so much as the era of KISS or the Eagles, but as the transgressive time of David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, and Freddie Mercury, of the huge commercial and creative triumphs of women-led bands like Fleetwood Mac and Heart, of punk and new wave outsiders setting the template for four decades of alternative rock: The Ramones, Patti Smith, the Sex Pistols, Blondie, The Clash, Joy Division, Talking Heads, Gary Numan, Kraftwerk…. We remember it, still, as a time when rock was mostly white, and when black artists mostly recorded disco, funk, soul, and R&B.

The record industry and radio markets had segregated, and it would stay that way into the 80s, though jazz artists like Miles Davis made serious inroads into rock experimentation, bands like Parliament/Funkadelic released hard rock psychedelia, Prince channeled both Little Richard and Chuck Berry, and early punks like Detroit’s Death and Philadelphia’s Pure Hell made groundbreaking punk and metal. The former escaped critical notice, but the latter became famous, then disappeared from rock history for decades.

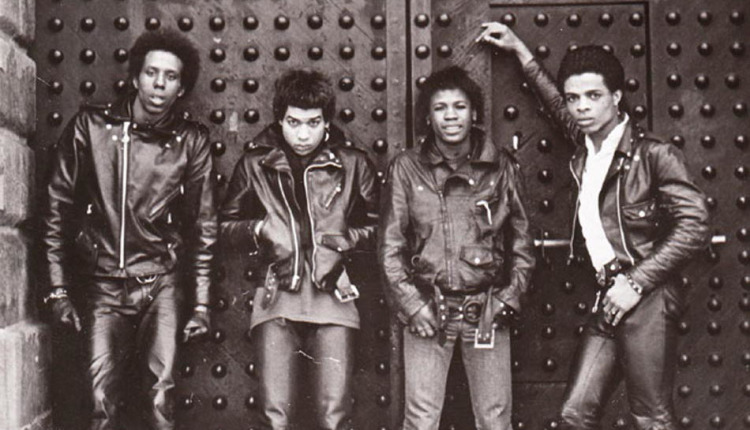

Death, the visionary trio of brothers who were recently rediscovered and celebrated, never really made it in their time outside of a small circle. Pure Hell, on the other hand, were an integral part of the New York punk scene and stars in Europe, and have been forgotten by most official punk histories. They “lived with the New York Dolls and played with Sid Vicious,” writes Cassidy George at Dazed, “but they’ve been largely written out of cultural history.” They are sometimes written back in, just as, to their dismay, they were promoted: as the “first black punk band.” But there’s far more to their history than that.

“I don’t want to be remembered just because we were black,” says singer Kenny “Stinker” Gordon. “I want to be remembered for being a part of the first tier of punk in the 70s.” He is not exaggerating. New York Dolls guitarist Johnny Thunders promoted the band, leading to gigs as Max’s Kansas City and a feature in Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, “marking their ‘place’ in a scene of cultural influencers.” They appeared in a 1978 issue of Melody Maker during their UK tour, in a photo with Sid Vicious, who wears his swastika t‑shirt and padlock and chain. (Gordon also wore a swastika t‑shirt onstage.) Just one of many second-page write-ups in Melody Maker, NME, and the European press.

All of the hype surrounding the band is part of the historical record, for those who look through backpages and archives, but their music has mostly gone unheard for over a generation, largely because their album Noise Addiction only came out in 2006. After they released their first single in ‘78, then refused to change their sound for a record deal, their manager Curtis Knight absconded with the master tapes and refused to release them. Listen to their debut single, a cover of “These Boots Are Made for Walking,” above. Melody Maker called it, with a wink, “the former Nancy Sinatra hit.” The song reached number four on the UK alternative charts.

Pure Hell describe their journey through the mid-seventies New York punk scene in the montage of interview clips at the top, scored by wicked, riff-laden recordings of their songs. The story began with four friends from a tough neighborhood in West Philadelphia. “We dressed in drag and wore wigs, basically daring people to bother us. People in the neighborhood would say, ‘Don’t go into houses with those guys, you may not come out!’” They were pressured to join a gang, says bassist Lenny “Steel” Boles, but refused. They packed up a U‑Haul and moved into the Chelsea Hotel, then played their first show across the street at Mother’s.

Legendary stories about the band abound. (They played Sid Vicious’ last appearance onstage and were caught up in the media circus surrounding Nancy Spungen’s death). What’s most interesting about them is the music and their lasting influence, despite what Boles describes as being “snubbed” by record labels unless they agreed to “do this Motown thing, saying like, ‘You guys are black so you’ve gotta do something that’s danceable.” After losing their manager and their masters, they settled in L.A., where they played with the Germs and the Cramps but “lost their momentum,” writes George.

“It was totally over by 1980,” says Gordon. All the same, their heavy proto-metal sound, drawing from reggae and Hendrix as much as from Bowie and Nancy Sinatra, sparked the admiration of many emerging punk bands, including Washington, DC legends Bad Brains, who acknowledge the debt their furious reggae/metal thrash owes to Pure Hell. Bad Brains broke color barriers in New York a few years later, and got most of the credit for it, largely because Pure Hell left behind nothing but a mysterious single and a “rumor,” says Henry Rollins, “that they had made an album and that it was sitting in a closet.”

After the tapes resurfaced, nearly everyone who heard the record became an instant fan, including Rollins. “If the album had come out when they made it, that would have been a game changer,” he says. “I believe [it] would have had a tremendous impact. It’s one of those missed opportunity stories.” But it is also a found opportunity story. They are now getting recognition for their music and historical role. In 2012 they reformed to play their first show since 1979, with Rancid, Buzzcocks, Public Image Ltd, and Social Distortion. Pure Hell will find their way back into the story of New York punk, and it will be a more interesting story for their rediscovery.

Related Content:

New Documentary Brings You Inside Africa’s Little-Known Punk Rock Scene

Four Female Punk Bands That Changed Women’s Role in Rock

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

“This despite the fact that rock and roll began as interracial music…”

Actually, RnR came directly from the Black community. It was quickly appropriated by Whites when they saw they could make money from it with White musicians.

calling rocknroll ‘black music’ is like calling basketball a ‘white game’ at least you can pinpoint to the exact white (mr. naismith) person who invented basketball…

but since you wanna get into racial identity and invention, black people didnt invent the electric guitar, not one item of recording technology or record fabrication, modern percussion, effects, musical notation, microphones, etc, etc…

wanna talk about the white man ripping off black artists? if it wasnt for white people youd have no recordings of any black artists ever. Still need more? How about you take a closer look at this band and how thier black manager curtis squire held on to this band’s masters for 30 years and kept them on purpose.

you just a race hustler and an uniformed malcontent