Jean-Michel Basquiat was keenly sensitive to the way the art market thought about him. He was compared to “a preacher possessed by the spirit,” his art, wrote critics, indicative of his “inner child.” This talk, writes Artnet’s Bruce Gopnik, “could easily veer into ideas of the Noble Savage.” The artist thought so; he was disgusted by his portrayal as “a wild man running around,” he said. He wanted no part of the primitivist image forced upon him. Yet “to this day, he’s almost always billed as being more in touch with his emotions and the passions of urban life than with the orderly reasoning of post-Enlightenment culture.”

This itself is a false dichotomy—between expressionist and conceptual art, “urban” passions and reason—but if anyone gets caught in-between, it’s Basquiat. Gopnick leans, maybe too heavily, on the conceptual side of things, pushing comparisons between Jenny Holzer and Hans Haacke, downplaying Basquiat’s roots as a street artist and his connections to hip hop and new wave. Basquiat had his ear to the street—also an artifact of post-Enlightenment culture—and was hardly comfortable with the orderly reasoning of the massively profitable art market.

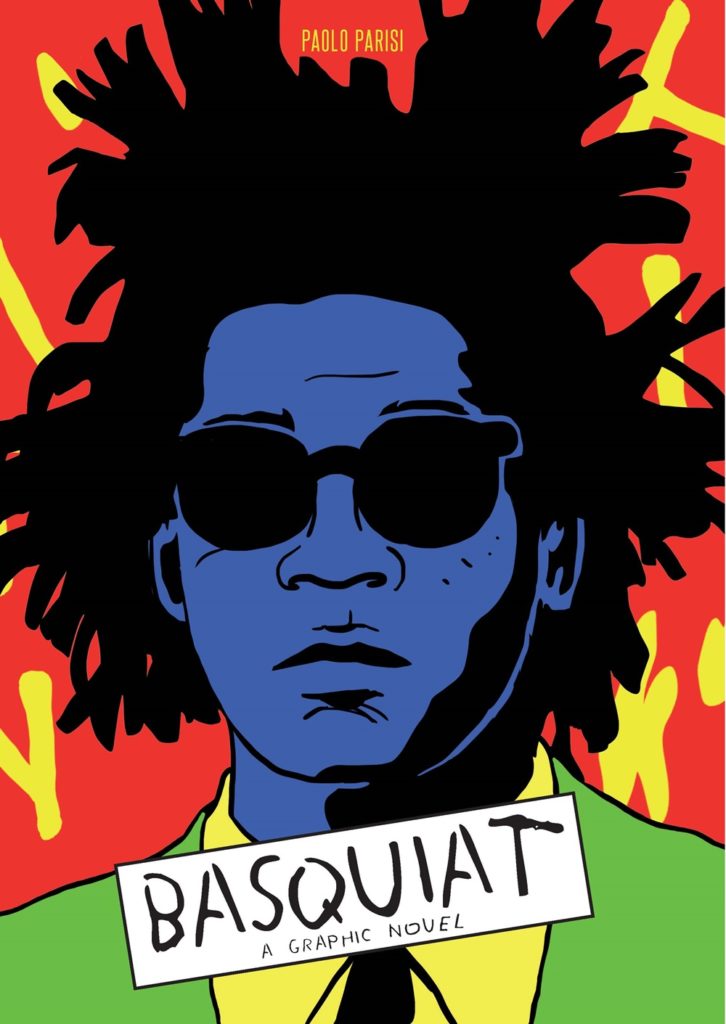

Whatever anyone wants to call his work, it makes no sense to separate it from its context: Basquiat’s Brooklyn home and Lower East Side stomping grounds, the downtown scene in which he came of age, his complicated relationships with Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, and Julian Schnabel, three of many figures who, along with Basquiat, created the huge 1980s art market and art gallery culture. A new graphic novel by Italian illustrator Paolo Parisi promises a new take on the now-well-worn biography of Basquiat. It’s a story written and drawn by a fellow conceptual artist, albeit one whose work more fits the image.

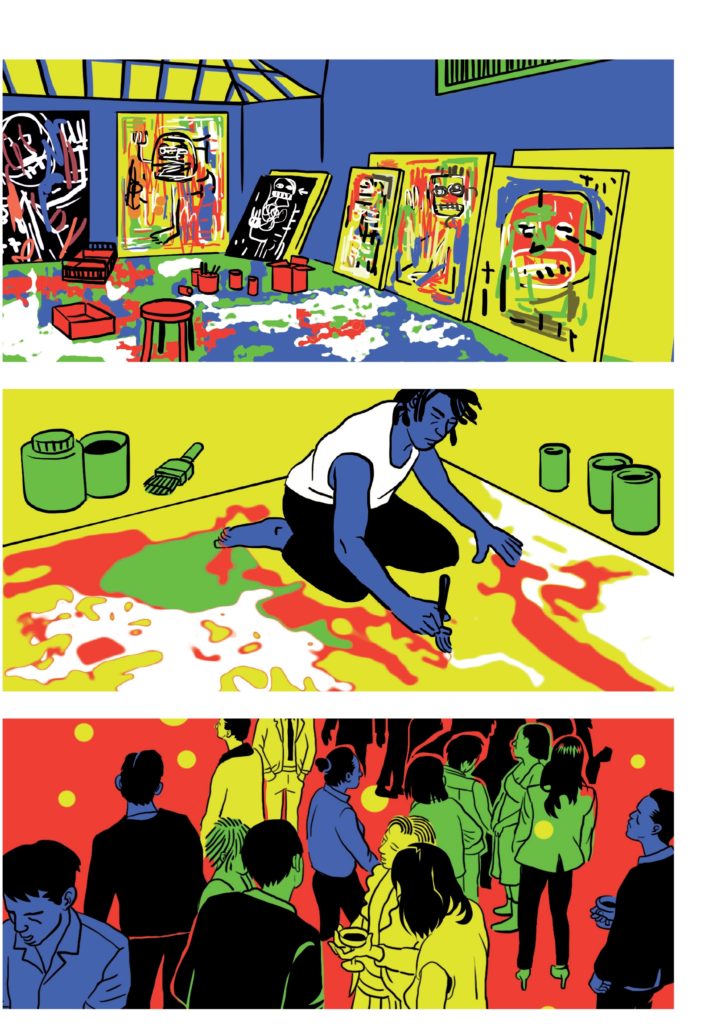

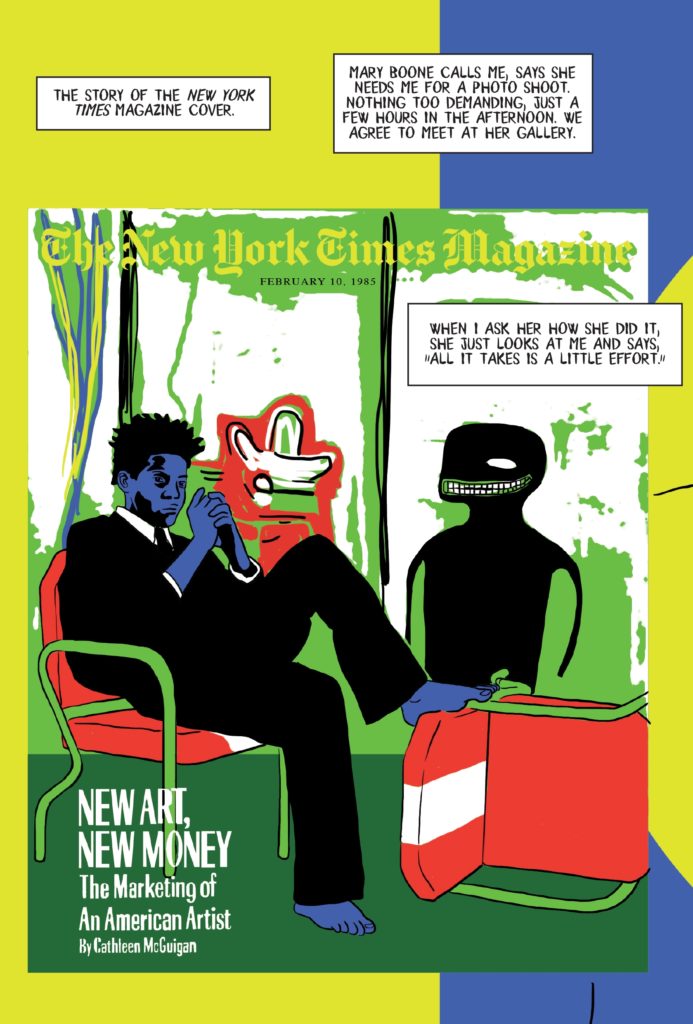

With eye-popping primary and secondary tones—the comic book colors favored by Basquiat and his contemporaries—Parisi takes some license, imagining conversations that may or may not have occurred. “Basquiat comes off as a bit more naïve and far less conflicted than we now know him to be,” writes Eileen Kinsella at Artnet. The chapter excerpted there, “New Art/New Money,” (see a few pages above and below), has multiple perspectives. In a reconstructed dinner scene between art dealers Mary Boone and Larry Gagosian, Basquiat doesn’t even appear.

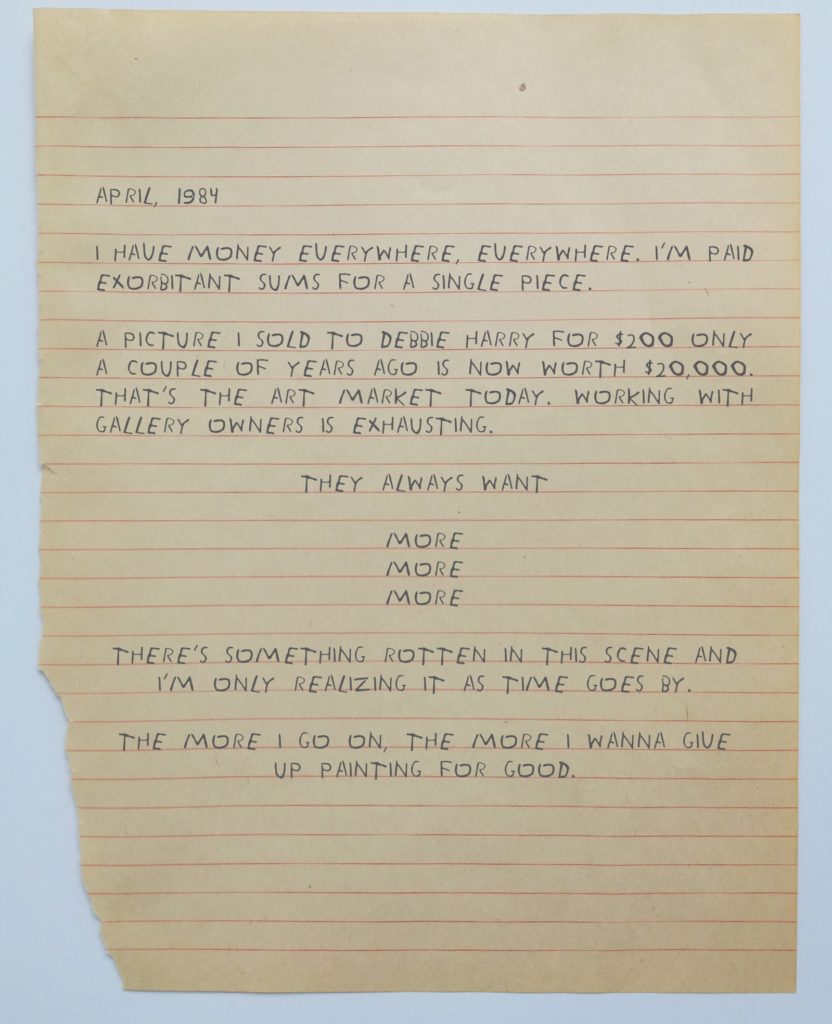

But the narrative also draws directly from Basquiat’s own words. One page is a facsimile of a handwritten note the artist made in April 1984. “I have money everywhere, everywhere. I’m paid exorbitant sums for a single piece,” he writes, not to boast but to marvel at the incredible amount of inflation he sees all around him:

A picture I sold to Debbie Harry for $200 only a couple of years ago is now worth $20,000. That’s the art market today. Working with gallery owners is exhausting.

They always want

More

More

More

Later Parisi adapts the artist’s thoughts in a critical monologue: The gallerists “have this way of doing things I’ve never seen before. They focus a lot on the artist’s image, buy in bulk, decide who to promote and how. They often buy and sell among themselves, between galleries. They never respect agreements. I don’t think I’ll be able to trust them.” Basquiat’s frustration at “something rotten in this scene” made him consider giving up painting for good. He didn’t get the chance, though Parisi has him tell a girlfriend “Picasso died at ninety… I’m certainly not going before then.”

Parisi, who has also written and illustrated graphic biographies of Billie Holiday and John Coltrane, has an ear for American speech patterns and class and race dynamics, drawing out with more or less subtlety the associations between the art world’s fascination with “primitivist” art and the continuing resonances of slavery and colonialism in its hyper-capitalist economy. Was Basquiat a childlike character who only slowly realized the greedy machinations of the dealers?

In the 2010 documentary The Radiant Child, his former graffiti partner Al Diaz explains his motivations from the very beginning. “We wanted to do some kind of conceptual art project.” Basquiat aimed directly at the art world, writing messages on walls like “4 THE SO-CALLED AVANT-GARDE.” Once in its company, however, he found, like many other fiercely independent artists who make it big, it wasn’t worth the money. Read the fully excerpted chapter at Artnet and purchase Parisi’s graphic novel Basquiat online.

via Artnet

Related Content:

The Story of How David Jones Became David Bowie Gets Told in a New Graphic Novel

Salvador Dalí & the Marx Brothers’ 1930s Film Script Gets Released as a Graphic Novel

How Art Spiegelman Designs Comic Books: A Breakdown of His Masterpiece, Maus

See also :

https://www.dessertdelune.be/store/p849/Visions_of_Basquiat_%2F%2F_Yves_Budin.html