The maxim “children need rules” does not necessarily describe either a right-wing position or a leftist one; either a political or a religious idea. Ideally, it points to observable facts about the biology of developing brains and psychology of developing personalities. It means creating structures that respect kids’ intellectual capacities and support their physical and emotional growth. Substituting “structure” for rules suggests even more strongly that the “rules” are mainly requirements for adults, those who build and maintain the world in which kids live.

Grown-ups must, to the best of their abilities, try and understand what children need at their stage of development, and try to meet those needs. When Susan Sontag’s son David was 7 years old, for example, the writer and filmmaker made a list of ten rules for herself to follow, touching on concerns about his self-concept, relationship with his father, individual preferences, and need for routine. Her first rule serves as a general heading for the prescriptions in the other nine: “Be consistent.”

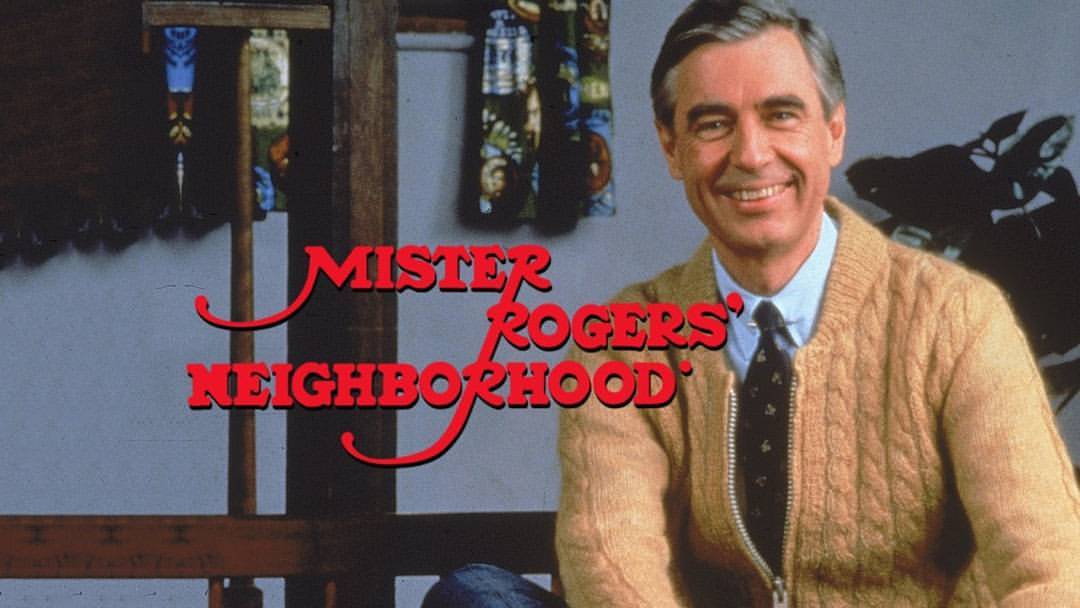

Sontag’s rules only emerged from her journals after her death. She did not turn them into public parenting tips. But nearly ten years after she wrote them, a man appeared on television who seemed to embody their exactitude and simplicity. From the very beginning in 1968, Fred Rogers insisted that his show be built on strict rules. “There were no accidents on Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood,” says former producer Arthur Greenwald. Or as Maxwell King, author of a recent biography on Rogers, writes at The Atlantic:

He insisted that every word, whether spoken by a person or a puppet, be scrutinized closely, because he knew that children—the preschool-age boys and girls who made up the core of his audience—tend to hear things literally…. He took great pains not to mislead or confuse children, and his team of writers joked that his on-air manner of speaking amounted to a distinct language they called “Freddish.”

In addition to his consistency, almost to the point of self-parody, Rogers made sure to always be absolutely crystal clear in his speech. He understood that young kids do not understand metaphors, mostly because they haven’t learned the commonly agreed-upon meanings. Preschool-age children also have trouble understanding the same uses of words in different contexts. In one segment on the show, for example, a nurse says to a child wearing a blood-pressure cuff, “I’m going to blow this up.”

Rogers had the crew redub the line with “’I’m going to puff this up with some air.’ ’Blow up’ might sound like there’s an explosion,” Greenwald remembers, “and he didn’t want kids to cover their ears and miss what would happen next.” In another example, Rogers wrote a song called “You Can Never Go Down the Drain,” to assuage a common fear that very young children have. There is a certain logic to the thinking. Drains take things away, why not them?

Rogers “was extraordinarily good at imagining where children’s minds might go,” writes King, explaining to them, for example, that an ophthalmologist could not look into his mind and see his thoughts. His care with language so amused and awed the show’s creative team that in 1977, Greenwald and writer Barry Head created an illustrated satirical manual called “Let’s Talk About Freddish.” Anyone who’s seen the documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? knows Rogers could take a good-natured joke at his expense, likely including the imaginative reconstruction of his methods below.

- “State the idea you wish to express as clearly as possible, and in terms preschoolers can understand.” Example: It is dangerous to play in the street.

- “Rephrase in a positive manner,” as in It is good to play where it is safe.

- “Rephrase the idea, bearing in mind that preschoolers cannot yet make subtle distinctions and need to be redirected to authorities they trust.” As in, “Ask your parents where it is safe to play.”

- “Rephrase your idea to eliminate all elements that could be considered prescriptive, directive, or instructive.” In the example, that’d mean getting rid of “ask”: Your parents will tell you where it is safe to play.

- “Rephrase any element that suggests certainty.” That’d be “will”: Your parents can tell you where it is safe to play.

- “Rephrase your idea to eliminate any element that may not apply to all children.” Not all children know their parents, so: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play.

- “Add a simple motivational idea that gives preschoolers a reason to follow your advice.” Perhaps: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. It is good to listen to them.

- “Rephrase your new statement, repeating the first step.” “Good” represents a value judgment, so: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. It is important to try to listen to them.

- “Rephrase your idea a final time, relating it to some phase of development a preschooler can understand.” Maybe: Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. It is important to try to listen to them, and listening is an important part of growing.

His crew respected him so much that even their parodies serve as slightly exaggerated tributes to his concerns. Rogers adapted his philosophical guidelines from the top psychologists and child-development experts of the time. The 9 Rules (or maybe 9 Stages) of “Freddish” above, as imagined by Greenwald and Head, reflect their work. Maybe implied in the joke is that his meticulous procedure, considering the possible effects of every word, would be impossible to emulate outside of his scripted encounters with children, prepped for by hours of conversation with child-development specialist Margaret McFarland.

Such is the kind of experience parents, teachers, and other caretakers never have. But Rogers understood and acknowledged the unique power and privilege of his role, more so than most every other children’s TV programmer. He made sure to get it right, as best he could, each time, not only so that kids could better take in the information, but so the grown-ups in their lives could make themselves better understood. Rogers wanted us to know, says Greenwald, “that the inner life of children was deadly serious to them,” and thus deserving of care and recognition.

via Mental Floss

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply