When we admire a famous artist from the past, we may wish to know everything about their lives—their private loves and hates, and the inner worlds to which they gave expression in canvases and sculptures. A biography may not be strictly necessary for the appreciation of an artist’s work. Maybe in some cases, knowing too much about an artist can make us see the autobiographical in everything they do. Frida Kahlo, on the other hand, fully invited such interpretation, and made knowing the facts of her life a necessity.

She can hardly “be accused of having invented her problems,” writes Deborah Solomon at The New York Times, yet she invented a new visual vocabulary for them, achieving her mostly posthumous fame “by making her unhappy face the main subject of her work.”

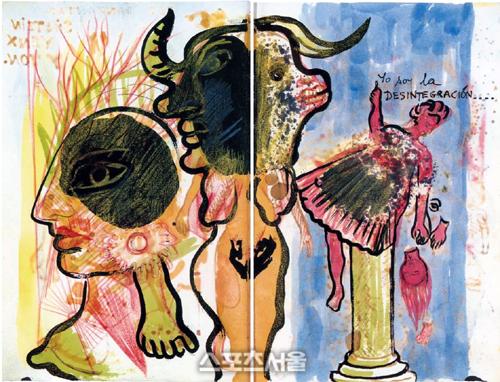

Her “specialty was suffering”—her own—“and she adopted it as an artistic theme as confidently as Mondrian claimed the rectangle or Rubens the corpulent nude.” Kahlo treated her life as worthy a subject as the respectable middle-class still lifes and aristocratic portraits of the old masters. She transfigured herself into a personal language of symbols and surreal motifs.

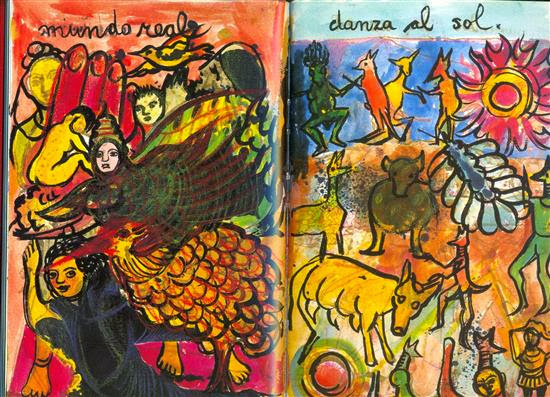

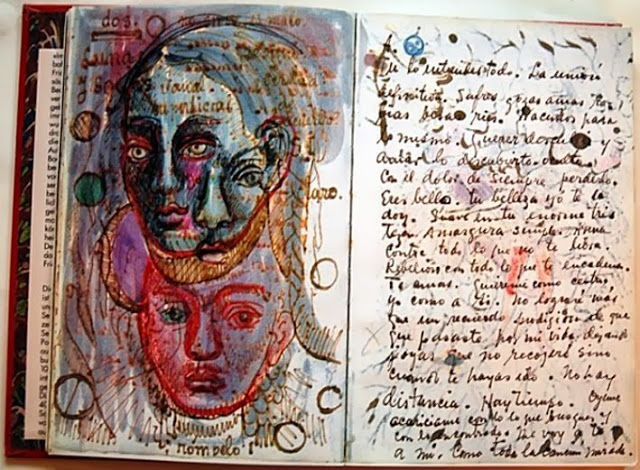

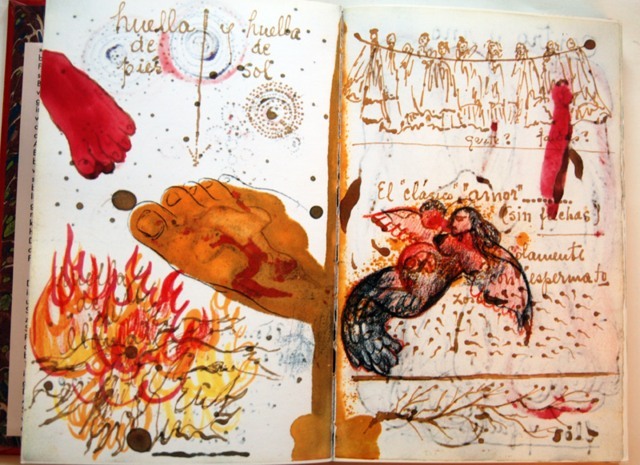

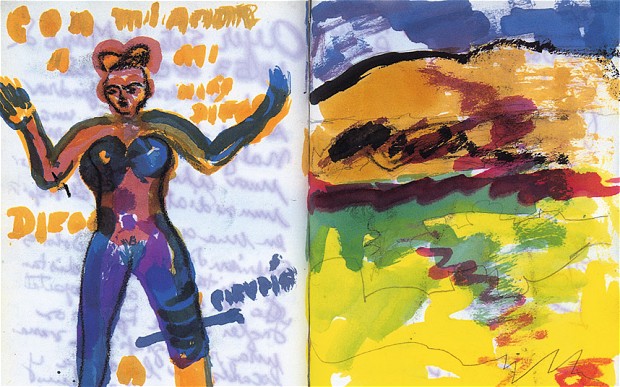

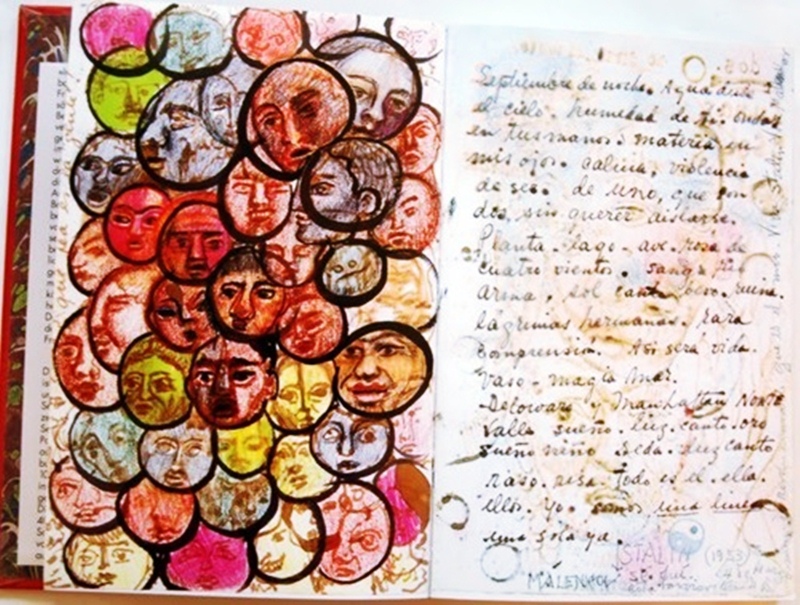

This means we must peer as closely into Kahlo’s life as we are able if we want to fully enter into what Museum of Modern Art curator Kirk Varnedoe called “her construction of a theater of the self.” But we may not feel much closer to her after reading her wildly-illustrated diary, which she kept for the last ten years of her life, and which was locked away after her death in 1954 and only published forty years later, with an introduction by Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes. The diary was then republished by Abrams in a beautiful hardcover edition that retains Fuentes’ introduction.

If you’re looking for a historical chronology or straightforward narrative, prepare for disappointment. It is, writes Kathryn Hughes at The Telegraph, a diary “of a very particular kind. There are few dates in it, and it has nothing to say about events in the external world—Communist Party meetings, appointments at the doctor’s or even trysts with Diego Rivera, the artist whom Kahlo loved so much that she married him twice. Instead it is full of paintings and drawings that appear to be dredged from her fertile unconscious.”

This descriptions suggests that the diary substitutes the image for the word, but this is not so—it is filled with Kahlo’s experiments with language: playful prose-poems, witty and cryptic captions, free-associative happy accidents. Like the visual autobiography of kindred spirit Jean-Michel Basquiat, her private feelings must be inferred from documents in which image and word are inseparable. There are “neither startling disclosures,” writes Solomon, “nor the sort of mundane, kitchen-sink detail that captivates by virtue of its ordinariness.” Rather than exposition, the diary is filled, as Abrams describes it, with “thoughts, poems, and dreams… along with 70 mesmerizing watercolor illustrations.”

Kahlo’s diary allows for no “dreamy identification with its subject” notes Solomon, through Instagram-worthy summaries of her dinners or wardrobe woes. Unlike her many, gushing letters to Rivera and other lovers, the “irony is that these personal sketches are surprisingly impersonal.” Or rather, they express the personal in her preferred private language, one we must learn to read if we want to understand her work. More than any other artist of the time, she turned biography into mythology.

Knowing the bare facts of her life gives us much-needed context for her images, but ultimately we must deal with them on their own terms as well. Rather than explaining her painting to us, Kahlo’s diary opens up an entirely new world of imagery—one very different from the controlled self-portraiture of her public body of work—to puzzle over.

Related Content:

Frida Kahlo’s Passionate Love Letters to Diego Rivera

A Brief Animated Introduction to the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply