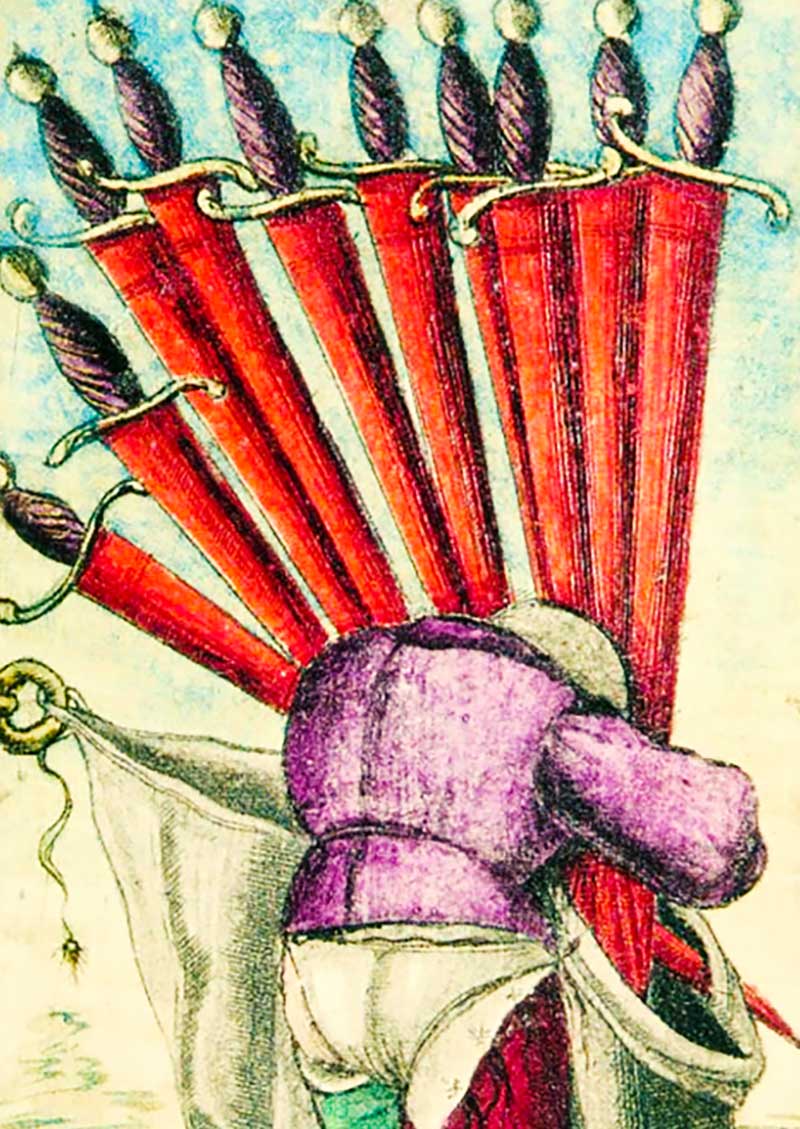

Whatever you think of the predictive power of tarot cards, the story of how humanity has produced them and put them to use provides a fascinating cultural history of the last 500 years or so. We’ve featured a variety of tarot decks here on Open Culture, mostly from the past century: decks designed by Aleister Crowley, Salvador Dalí, and H.R. Giger, as well as one featuring the characters from Twin Peaks. But today we give you the oldest extant example, and a highly distinctive one for reasons not just historical but aesthetic: the Sola-Busca tarot deck, dating from the early 1490s, which L’Italo Americano’s Francesca Bezzone describes as “78, beautifully illustrated cards, 22 major arcana and 56 minor arcana, engraved on cardboard and hand painted with tempera colors and gold.”

The Sola-Busca tarot deck, whose name derives from those of its last two owners Marquise Busca and Count Sola, set a structural precedent for decks to come by being divided into those sets of major arcana (or “major secrets”) and minor arcana (or “minor secrets”).

In the cards of the major arcana, which trace the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, “Classical and Biblical figures take the place of traditional tarot illustrations: for instance, the arcana of justice is Nero and that of the world is Nebuchadnezzar. Among others represented Gaius Marius, uncle of Juluis Caesar, and Bacchus,” as well as now more difficult-to-identify personages from later centuries. The minor arcana cards, writes Bezzone, “are also different from all other decks’, because they are finely and richly illustrated with scenes of daily life.”

But even the everyday images contain secrets: “This is particularly evident in the suit of coins, which apparently illustrates the process of coin minting, but in reality alludes to the complex and secret practices of the Opus Alchemicum, that is, the method used to create the lapis philosophorum, the philosopher’s stone, alchemic instrument of immortality and perfection.” But “in spite of the refined and delicate artistry behind their illustrations, the name of the man, or men, who created them remained shrouded in darkness for centuries,” though in 1938 art historian Arthur Mayger Hind determined that, based on the references to the Republic of Venice in the deck’s artwork, its was likely made for a Venetian client, possibly by the engraver Mattia Serrati da Cosandola or, according to another theory, the painter Nicola di Maestro Antonio and historian Marin Sanudo.

Il segreto dei segreti, an exhibition on the Sola-Busca deck at Milan’s Pinacoteca di Brera gallery, brings another Renaissance figure into the mix: “While largely unknown today, the Humanist and Hermeticist Ludovico Lazzarelli from San Severino Marche played a significant role in Italian court Humanism,” and because of “his personality, role, and interest in Hermetic and alchemical themes” as well as his relations with powerful courts of the day “is believed to have designed the complex iconographical program of the Sola-Busca tarots.” The tenets of Renaissance Hermeticism held that mankind could transform nature by apprehending it, making it in some sense a forerunner to modern scientific thinking. And while the notion that we can see our future in the turn of playing cards may not itself sound wildly scientific, an artifact like the Sola-Busca deck, all of whose 78 carts you can see here, still has more to teach us about our past. Decks can also be purchased online.

Related Content:

Alejandro Jodorowsky Explains How Tarot Cards Can Give You Creative Inspiration

The Tarot Card Deck Designed by Salvador Dalí

The Thoth Tarot Deck Designed by Famed Occultist Aleister Crowley

Twin Peaks Tarot Cards Now Available as 78-Card Deck

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Awesome lesson

Colin -

I’m new to Open Culture, and I’ve really enjoyed your work over the last couple of months. Great subjects, (many of which I also have interest in), and excellent writing.

This piece prompted me to drag out several Tarot decks that I own as well as several books on the subject, because I thought that I remembered a different deck was considered to be the oldest. I discovered that I was kind of right.

Historians agree (generally) that the Carry-Yale Visconti Tarocchi Deck is most likely the oldest, putting its creation at about 1441. (Stuart Kaplan) However, the style was quite different from what we now recognize as the modern Tarot Cards, with a total of 86 cards as well. While another deck considered to be a few years younger, the Brambilla, had 78, there were still many symbols and patterns that were a reflection of the wealthy patrons’ families that commissioned the cards. None of these early decks are complete today.

It was several years later that the illustrations became more standardized and more similar to the classic cards of the last century. So the Sola-Busca cards are, as you say, the earliest complete set that is also more recognizable as the Tarot most people know, but not the oldest known deck. And it may be possible that you didn’t mean it was the oldest, but just the oldest complete. But you still got me going.

So thank you for sending me down that rabbit hole and inspiring a couple of hours of really satisfying research and learning! It’s something I enjoy very much.

Carry on!

Frankly, the 3 of swords thru the heart is as macabre as catholocism’s paintings of thorns around a heart revealed by an open chest cavity. If everyone (as all of us who try to recall as a child) would remember that horror, we should all ask ourselves what purpose was intended by such imagery as even necessary? Instead cosmic themes more conducive to elevating our thoughts in lieu of shocking them? Wrote to both the American Psychiatric Assoc as well as the American Psychological Assoc re: another form of the ink blot test that could be more encompassing in scope, an interesting “little reveal” when a woman replied to my posted reaction (of a wildlife photo) of a wolf resting under a snowladen evergreen’s bough. Marveled at how the wolf’s expression was akin to a wise old Oriental man observing “foolish behavior” with aloof distain. Yet all she saw was consummate evil. Perhaps by not sharing a medieval (d/evil) image in our divinatory tools, we’d more quickly discern the Inner Self more worthy of scrutiny than an archetype?