Art depends on popular judgments about the universe, and is nourished by the limited expanse of sentiment. . . . In contrast, science was barely touched upon by the ancients, and is as free from the inconsistencies of fashion as it is from the fickle standards of taste. . . . And let me stress that this conquest of ideas is not subject to fluctuations of opinion, to the silence of envy, or to the caprices of fashion that today repudiate and detest what yesterday was praised as sublime.

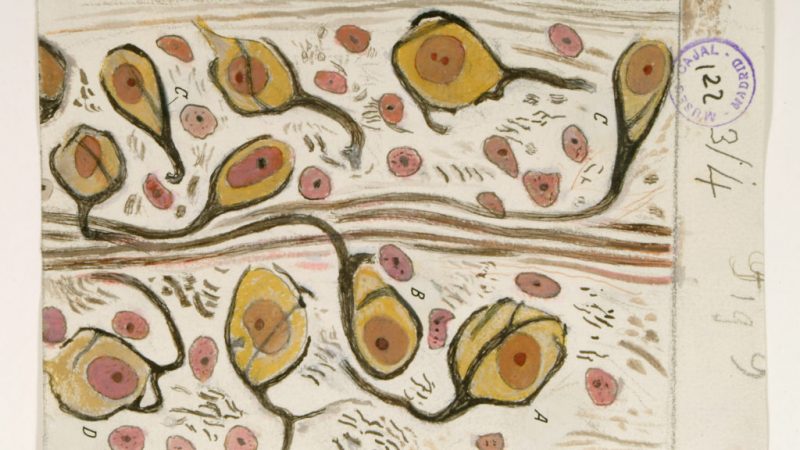

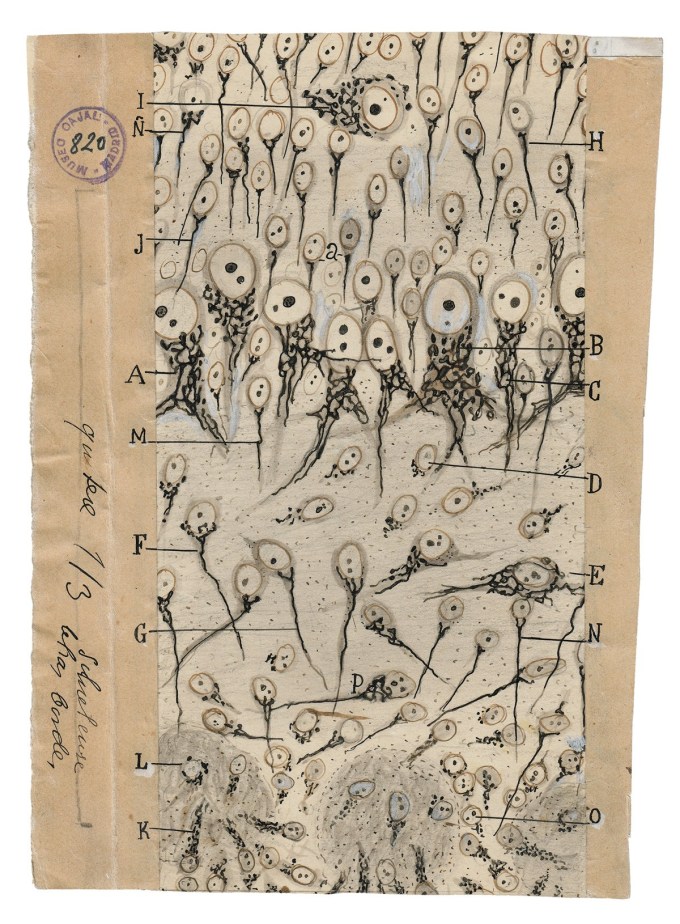

The above drawing is the sort of sublime rendering that attracts throngs of visitors to the world’s great modern art museums, but that’s not the sort of renown the artist, Nobel Prize-winning father of modern neuroscience Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852 ‑1934), actively sought.

Or rather, he might have back before his father, a professor of anatomy, coerced his wild young son into transferring from a provincial art academy to the medical school where he himself was employed.

After a stint as an army medical officer, the artist-turned-anatomist concentrated on inflammation, cholera, and epithelial cells before zeroing in on his true muse—the central nervous system.

At the time, reticular theory, which held that everything in the nervous system was part of a single continuous network, prevailed.

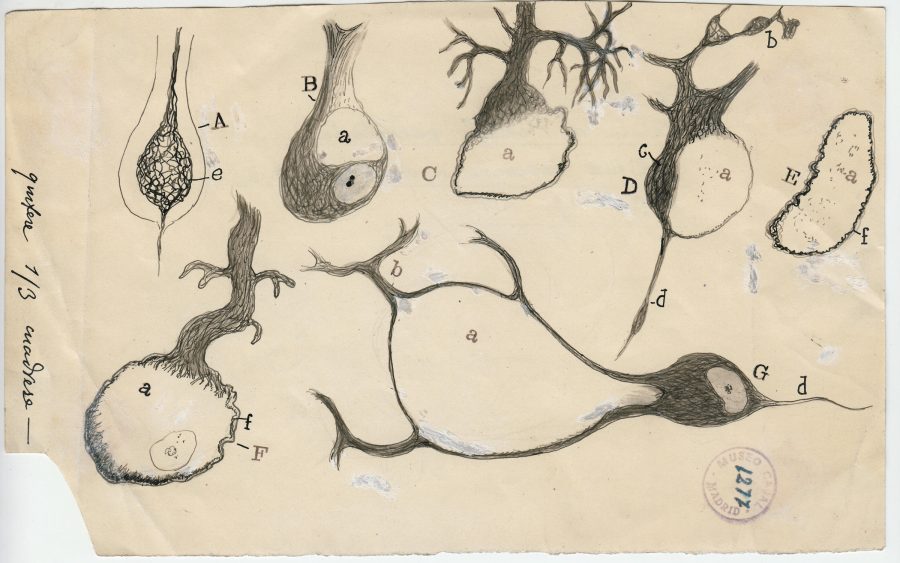

Ramón y Cajal was able to disprove this widely held belief by using Golgi stains to support the existence of individual nervous cells—neurons—that, while not physically connected, communicated with each other through a system of axons, dendrites, and synapses.

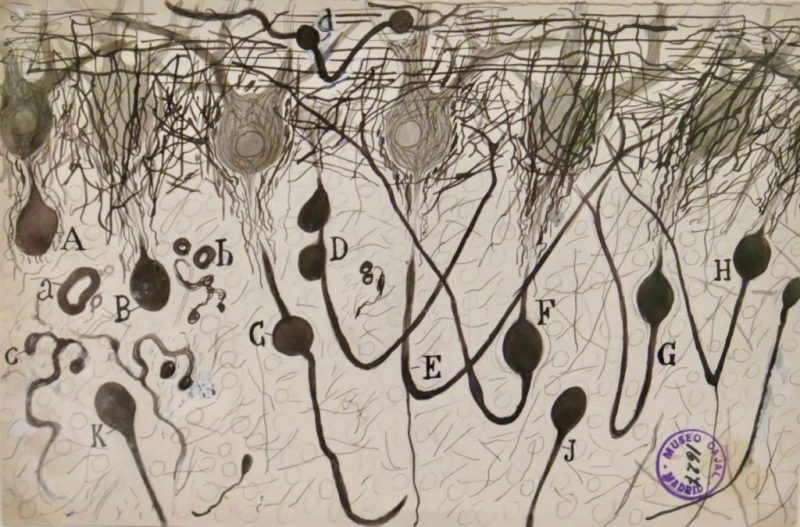

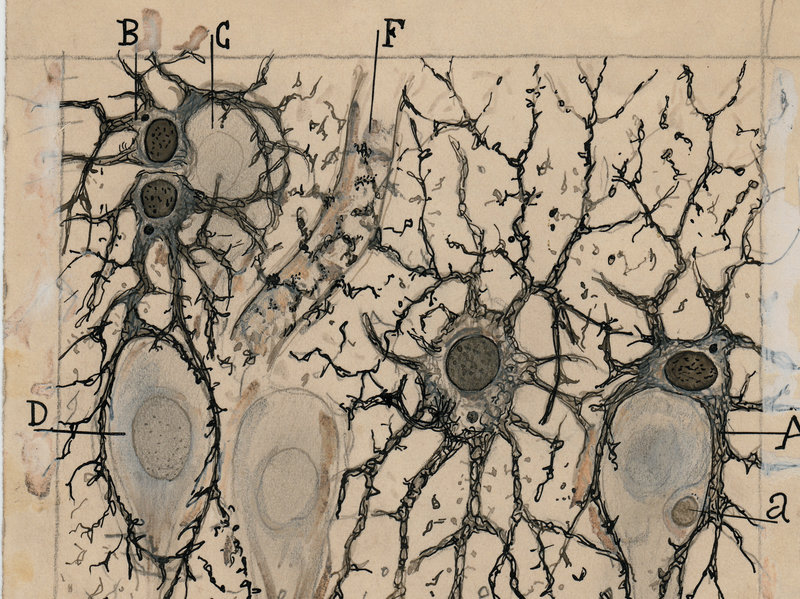

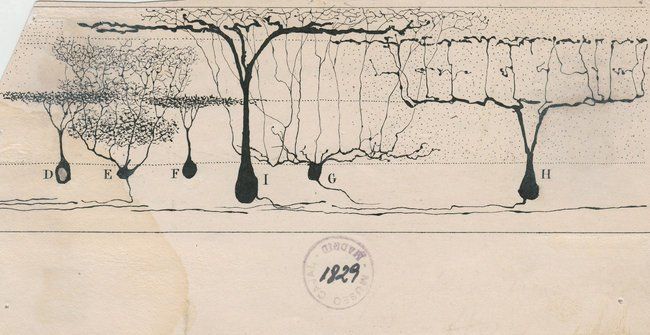

He called upon both his artistic and medical training in documenting what he observed through his microscope. His meticulous freehand drawings are far more accurate than anything that could be produced by the microscopic-image photographic tools available at the time.

His precision was such that his illustrations continue to be published in medical textbooks. Further research has confirmed many of his suppositions.

As art critic Roberta Smith writes in The New York Times, the drawings are “fairly hard-nosed fact if you know your science”:

If you don’t, they are deep pools of suggestive motifs into which the imagination can dive. Their lines, forms and various textures of stippling, dashes and faint pencil circles would be the envy of any modern artist. That they connect with Surrealist drawing, biomorphic abstraction and exquisite doodling is only the half of it.

The drawings’ pragmatic titles certainly take on a poetic quality when one considers the context of their creation:

Axon of Purkinje neurons in the cerebellum of a drowned man

The hippocampus of a man three hours after death

Glial cells of the cerebral cortex of a child

His specimens were not limited to the human world:

Retina of lizard

The olfactory bulb of the dog

In his book Advice for a Young Investigator, Ramón y Cajal took a holistic view of the relationship between science and the arts:

The investigator ought to possess an artistic temperament that impels him to search for and admire the number, beauty, and harmony of things; and—in the struggle for life that ideas create in our minds—a sound critical judgment that is able to reject the rash impulses of daydreams in favor of those thoughts most faithfully embracing objective reality.

Explore more of Ramón y Cajal’s cellular drawings in Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the companion book to a recent traveling exhibition of his work. Or immerse yourself at the neural level by ordering a reproduction on a beach towel, yoga mat, cell phone case, shower curtain, or other necessity on Science Source.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in New York City April 15 for the next installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply