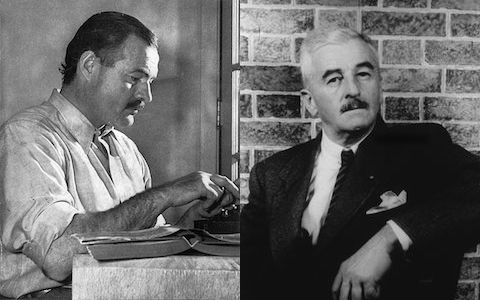

Images via Wikimedia Commons

In the mid-20th century, the two big dogs in the American literary scene were William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway. Both were internationally revered, both were masters of the novel and the short story, and both won Nobel Prizes.

Born in Mississippi, Faulkner wrote allegorical histories of the South in a style that is both elliptical and challenging. His works were marked by uses of stream-of-consciousness and shifting points of view. He also favored titanically long sentences, holding the record for having, according to the Guinness Book of Records, the longest sentence in literature. Open your copy of Absalom! Absalom! to chapter 6 and you’ll find it. Hemingway, on the other hand, famously sandblasted the florid prose of Victorian-era books into short, terse, deceptively simple sentences. His stories were about rootless, damaged, cosmopolitan people in exotic locations like Paris or the Serengeti.

If you type in “Faulkner and Hemingway” in your favorite search engine, you’ll likely stumble upon this famous exchange — Faulkner on Hemingway: “He has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary.” Hemingway: “Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words?” Zing! Faulkner reportedly didn’t mean for the line to come off as an insult but Hemingway took it as one. The incident ended up being the most acrimonious in the two authors’ complicated relationship.

While Faulkner and Hemingway never formally met, they were regular correspondents, and each was keenly aware of the other’s talents. And they were competitive with each other, especially Hemingway who was much more insecure than you might surmise from his macho persona. While Hemingway regularly called Faulkner “the best of us all,” marveling at his natural abilities, he also hammered Faulkner for resorting to tricks. As he wrote to Harvey Breit, the famed critic for The New York Times, “If you have to write the longest sentence in the world to give a book distinction, the next thing you should hire Bill Veek [sic] and use midgets.”

Faulkner, on his end, was no less competitive. He once told the New York Herald Tribune, “I think he’s the best we’ve got.” On the other hand, he bristled when an editor mentioned getting Hemingway to write the preface for The Portable Faulkner in 1946. “It seems to me in bad taste to ask him to write a preface to my stuff. It’s like asking one race horse in the middle of a race to broadcast a blurb on another horse in the same running field.”

When Breit asked Faulkner to write a review of Hemingway’s 1952 novella The Old Man and the Sea, he refused. Yet when a couple months later he got the same request from Washington and Lee University’s literary journal, Shenandoah, Faulkner relented, giving guarded praise to the novel in a one paragraph-long review. You can read it below.

His best. Time may show it to be the best single piece of any of us, I mean his and my contemporaries. This time, he discovered God, a Creator. Until now, his men and women had made themselves, shaped themselves out of their own clay; their victories and defeats were at the hands of each other, just to prove to themselves or one another how tough they could be. But this time, he wrote about pity: about something somewhere that made them all: the old man who had to catch the fish and then lose it, the fish that had to be caught and then lost, the sharks which had to rob the old man of his fish; made them all and loved them all and pitied them all. It’s all right. Praise God that whatever made and loves and pities Hemingway and me kept him from touching it any further.

And you can also watch below a fascinating talk by scholar Joseph Fruscione about how Faulkner and Hemingway competed and influenced each other. He wrote the recent book, Faulkner and Hemingway: Biography of a Literary Rivalry .

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in July 2014.

Related Content:

Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer, 1934

See a Beautifully Hand-Painted Animation of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (1999)

The Art of William Faulkner: Drawings from 1916–1925

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.

Unfortunately the quote above by Faulkner about Hemingway readers not needing to go to the dictionary, is taken out of context and is only the partial quote. The video above shows the full quote, and from that we can easily see more harmful intent from Faulkner.

Fragile egos, well balanced between the two.

I remember reading Hemingway referred to Faulkner as “old mellifluous”, at least once.

A perfect moniker (and a pretty big word, arguably) coined by Hemingway.

Anyway, a great Faulknerian paragraph of a review by the man himself.