The truth, they say, is stranger than fiction — or at least it is in the work of Herodotus, the ancient Greek writer and traveler often described as “the Father of History” (and a favorite writer of none other than Jorge Luis Borges). But go back far enough in history itself, and the boundary between truth and fiction grows much blurrier than it is even today: mention Herodotus in mixed company, and someone will surely bring up the phoenixes, horned serpents, winged snakes, gold-digging giant ants, and everything else for whose existence he implausibly vouches in The Histories (440 BC). And what of the baris, a boat made of “thorny acacia,” in Herodotus’ words, that “cannot sail up the river unless there be a very fresh wind blowing, but are towed from the shore?”

Images courtesy of Christoph Gerigk/Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation

“They have a door-shaped crate made of tamarisk wood and reed mats sewn together,” Herodotus’ description of the baris continues, “and also a stone of about two talents weight bored with a hole.” Despite the detail he went into, one translation of which you can read here, no archaeological findings ever confirmed the existence of such a boat — or at least, they didn’t until very recently.

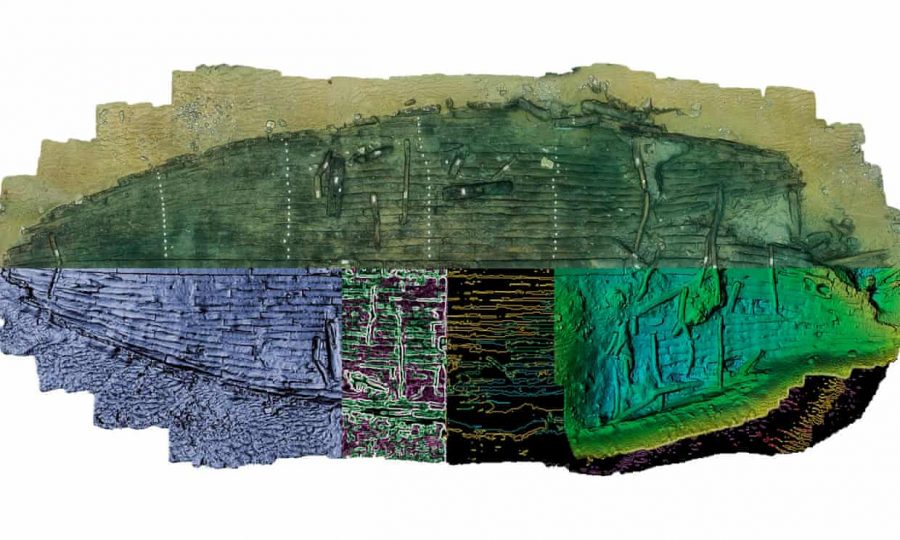

According to the Guardian’s Dalya Alberge, “a ‘fabulously preserved’ wreck in the waters around the sunken port city of Thonis-Heracleion has revealed just how accurate the historian was.” The sunken Ship 17, as it has been named, has “a vast crescent-shaped hull and a previously undocumented type of construction involving thick planks assembled with tenons – just as Herodotus observed, in describing a slightly smaller vessel.”

“Prior to Ship 17’s discovery,” writes Smithsonian.com’s Meilan Solly, “contemporary archaeologists had never encountered this architectural style. But upon examining the hull’s well-preserved remains, which constitute some 70 percent of the original structure, researchers found a singular feat of design.” Though Herodotus may have indulged in exaggeration now and again, Ship 17 turns out to be more impressive than the boat in The Histories: “At the peak of its maritime career, Ship 17 likely measured up to 92 feet — significantly longer than the baris described by Herodotus.” You can learn more about Ship 17 and its historical implications from the Ancient Architects video at the top, as well as from articles at Atlas Obscura, History.com, and Science Alert. All this makes the engineering skills of the ancient Egyptians, as well as the recording skills of Herodotus, look that much more impressive. But it does raise an important question: should we now start thinking about how best to hide our gold from the ants?

The images above come from

Related Content:

Try the Oldest Known Recipe For Toothpaste: From Ancient Egypt, Circa the 4th Century BC

An Ancient Egyptian Homework Assignment from 1800 Years Ago: Some Things Are Truly Timeless

Jorge Luis Borges Selects 74 Books for Your Personal Library

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Don’t get too concerned with ridiculing the gold-digging ants. They were as real as the boat.

It has been fairly safely established that they refer to marmots in India, where they do dog up gold, or at least burrow in gold rich parts of the Indus Valley and Sikkim and emerge from their burrows spotted with gold dust.

Size, behaviour, location and local myth are all identical with his description apart from actually being ants.

Several other creatures were clearly myth and legend, but probably no less ‘factual’ than a modern reference to the ‘four corners of the earth’ or the North Pole — his readers would no more think of a living Griffin than a modern reader would a flat earth or a big tower in the artic. Indeed, with the information available on you tube possibly less so!