For most of publishing history, books for children meant primers and preachy religious texts, not mythical worlds invented just for kids. It’s true that fairy tales may have been specifically targeted to the young, but they were never childish. (See the original Grimms’ tales.) By the 19th century, however, the situation had dramatically changed. And by the turn of the century, childlike fairy stories and fantasies enjoyed wide popularity among grown-ups and children alike, just as they do today. Witness the tremendous success of Peter Pan.

The character first appeared as a seven-day-old baby in a satirical 1902 fantasy novel by Scottish writer J.M. Barrie. The novel became a play. Pan was so beloved that Barrie’s publisher excerpted his chapters and published them as Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens.

Then followed Barrie’s 1904 play, Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, in which baby Pan had grown up at least just a little. Only after this history of Pan entertainments did Barrie write Peter and Wendy, the story we learned as children through Disney adaptations or the 1911 original.

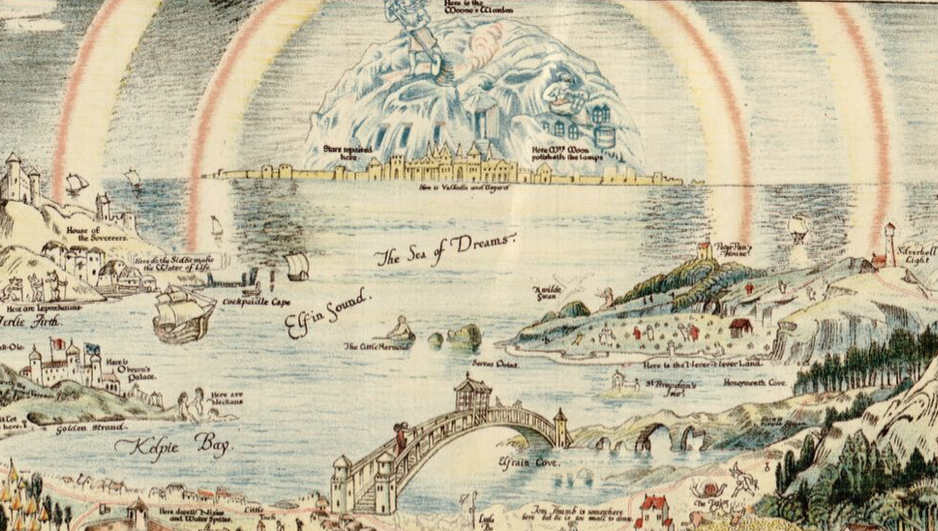

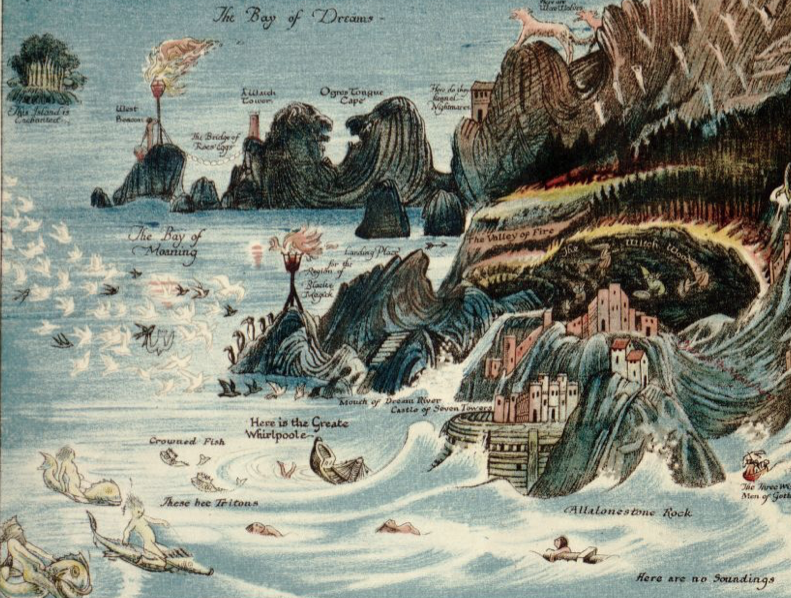

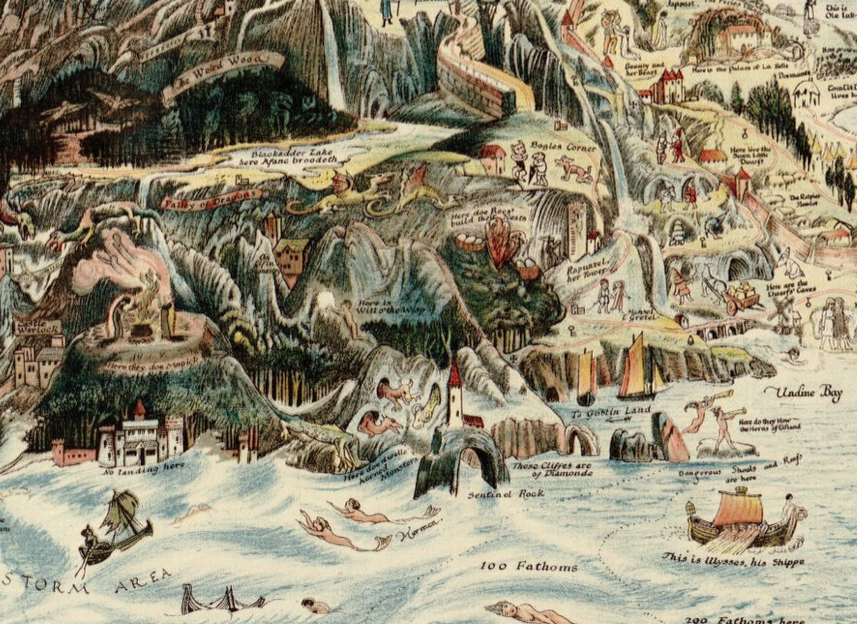

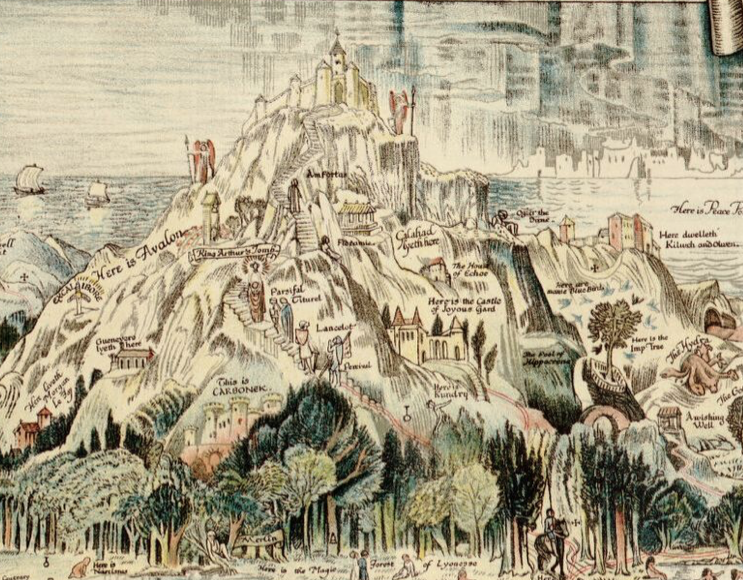

Pan’s influence is wide and deep, and over a century long. In 1917, one of the early adopters of Barrie’s Neverland fantasy concept expanded on its world with a version called “Fairyland,” described in an illustrated map of such a place. The artist, Bernard Sleigh, “begins with a stormy sea,” writes Jessica Leigh Hester at Atlas Obscura. (That is, if we read the map from left to right.) “There, waves lash the shore and tritons ride piscine steeds, while a wooden ship and an unfortunate soul are half-sunk nearby, in a white whirlpool.” The influence of J.M. Barrie’s descriptions is readily apparent.

The Anciente Mappe of Fairyland (see the map in full here) “mashes up dozens of stories to make a comprehensive geography of make-believe,” writes Slate’s Rebecca Onion: “Rapunzel’s tower, cheek by jowl with Belle’s palace from ‘Beauty and the Beast’; Humpty Dumpty on a roof, overlooking Red Riding Hood’s house; Ulysses’ ship, sailing past Goblin Land.” It’s a “Where’s Waldo of Fantasy Easter Eggs,” by an English landscape painter “who wrote extensively about fairies in England.” Sleigh was not only a fantasist, he was also a true believer.

Like Arthur Conan Doyle, Sleigh promoted the existence of fairies, and wrote an earnest work of fiction called The Gates of Horn: Being Sundry Records from the Proceedings of the Society for the Investigation of Fairy Fact and Fallacy in 1926. Like Doyle, he was a talented and popular artist looking for magic in a world of machinery. “The ancient map of Fairyland,” with its visual anthology of literature, folk tale, and mythology, “is said to have been his most famous work,” writes the David Rumsey Map Collection. It was designed “during the ‘Arts & Crafts’ movement, which was in reaction to the Industrial revolution.”

Like J.R.R. Tolkien, another artist who found inspiration in Barrie’s fantasy world, Sleigh worked against a backdrop of world war. Onion quotes historians Tim Bryars and Tom Harper’s comment that “compared with the devastated, bomb-blasted landscape of northern France, this vision of a make-believe land may have seemed a seductive escape for a European society bearing the psychological and physical scars of mass conflict.”

Unlike Tolkien, however, or contemporary inheritors of the Peter Pan tradition like J.K. Rowling a century later, or the earlier Romantic lovers of mythology and folk tale, Sleigh’s map invites a light reprieve from the horrors of war. “Any small amount of violence or trauma you might find in ‘Fairyland’ could easily be evaded,” writes Onion, “by moving on to the next area of the map, where a new set of stories unfolds.”

Download high resolution scans of An Anciente Mappe of Fairyland: newly discovered and set forth from the Library of Congress and the David Rumsey Map Collection, where you can also purchase a print. (The map physically resides at the British Library.) Zoom into Fairyland’s intricate fantasy landscape and maybe take a break from the dark realities of yet another industrial revolution and a world at war.

Related Content:

Map of Middle-Earth Annotated by Tolkien Found in a Copy of Lord of the Rings

A Digital Archive of 1,800+ Children’s Books from UCLA

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

This was extremely cool!