The United Nations, as you may or may not know, has designated 2019 the Year of Indigenous Languages. By fortunate coincidence, this year also happens to mark the tenth anniversary of the Endangered Alphabets Project. In 2009, its founder writes, “times were dark for indigenous and minority cultures.” Television and the internet had driven “a kind of cultural imperialism into every corner of the world. Everyone had a screen or wanted a screen, and the English language and the Latin alphabet (or one of the half-dozen other major writing systems) were on every screen and every keyboard” — putting at a great disadvantage those who could only read and write, say, Mandombe, Wancho, or Hanifi Rohingya.

2019, by contrast, turns out to be “a remarkable time in the history of writing systems” when, “in spite of creeping globalization, political oppression, and economic inequalities, minority cultures are starting to revive interest in their traditional scripts.”

A variety of these scripts have found new lives as the material for works of art and design, and they’ve also received new waves of preservation-minded attention from activist groups and governments alike. But that doesn’t guarantee their survival through the 21st century, an unfortunate fact toward which the Endangered Alphabets Project’s Atlas of Endangered Alphabets exists to draw attention.

Not all the scripts included in the Atlas are alphabets — “some are abjads, or abugidas, or syllabaries. A couple are even pictographic systems” — but all lack “official status in their country, state, or province” and “are not taught in government-funded schools.” All once enjoyed “widespread acceptance and use within their cultural and linguistic community,” but none do any longer, and though none are actually extinct, all suffer from endangerment as a consequence of their declining or emerging status (as well as, often, of “being dominated, bullied, ignored, or actively persecuted by another, more powerful culture”). You can explore the endangered languages by scrolling, zooming, and clicking the world map on the atlas’ front page.

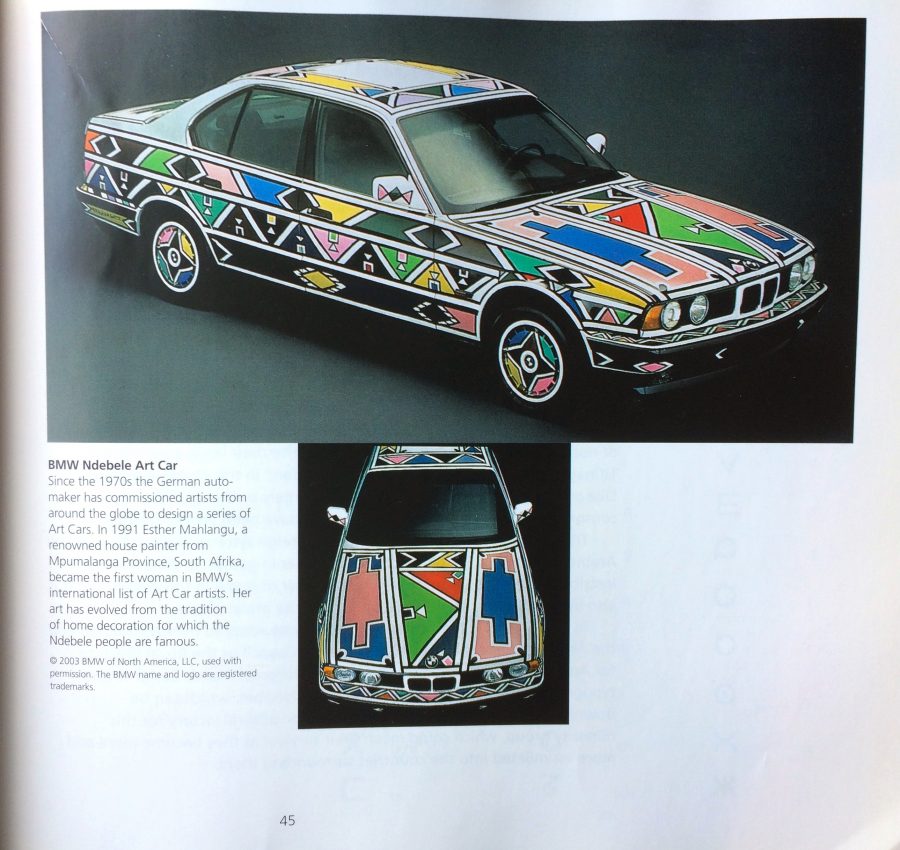

Or you can browse them all, from Adlam to Zo, on an alphabetically ordered list — ordered, of course, by the Roman alphabet, but full of examples of writing systems that differ in many and often surprising ways from it. Take, for example, the African Ditema tsa Dinoko script, which allows the writer to express with not just shape but color. Developed between 2010 and 2015 to write southern Bantu languages, it takes its forms from southern African murals of the kind painted by Esther Mahlangu, whose BMW art car appears in the Atlas of Endangered Alphabets’ gallery. BMW might consider commissioning another one emblazoned with official Ditema tsa Dinoko letters. With promotion that snazzy, what writing system could possibly go extinct?

Related Content:

You Could Soon Be Able to Text with 2,000 Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Thanks so much for mentioning the Atlas!

You are very welcome!

Dan

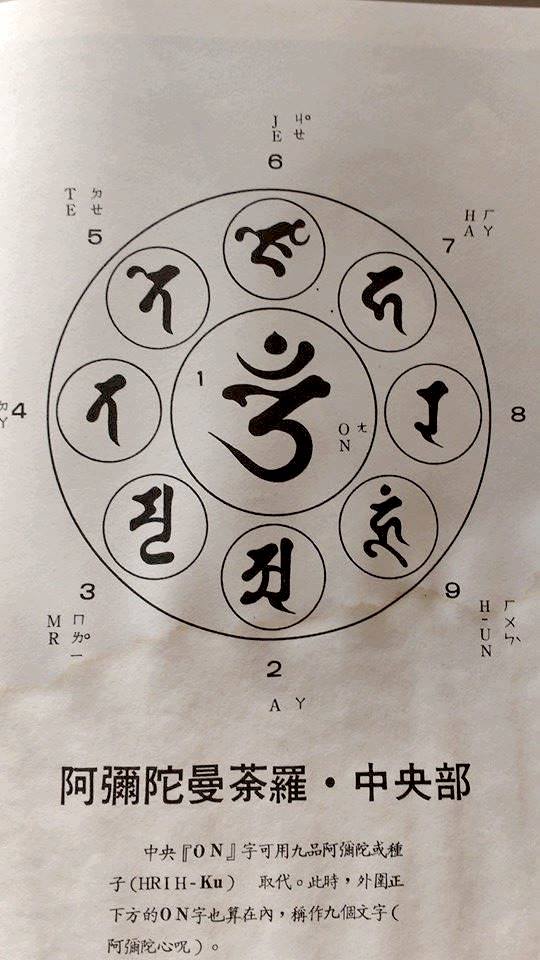

What is the second picture, which shows something like a part of a mandala with Siddam, English, and Japanese? I am a Japanese, and it looks chaotic for me. Could you tell me what it is? Thank you.

Based on the image title, it appears to be Medefaidrin.