For hundreds of years before the regular use of dictation machines, word processors, and computers, many thousands of court records, correspondence, journalism, and so on circulated in translation. All of these texts were originally in their native language, but they were transcribed in a different writing system, then translated back into the standard orthography, by stenographers using various kinds of shorthand. In English, this meant that a mess of irregular, phonetically nonsensical spellings turned into a streamlined, orderly symbolic system, impenetrable to anyone who hadn’t studied it thoroughly.

I do not know the rates of accuracy in shorthand writing or translation. Nor do I know how many original shorthand manuscripts still exist for comparison’s sake. But for centuries, shorthand systems were used to record lectures, letters, and interviews, and to write edicts, essays, articles, etc., in Imperial China, ancient Greece and Rome, and modern Europe, North America, and Japan.

The practice reached a peak in the late nineteenth and early 20th centuries, when stenography became a growth industry. Jack El-Hai at Wonders and Marvels explains.

A century ago, hundreds of thousands of people around the world regularly used shorthand. Secretaries, stenographers, court reporters, journalists and others depended on the elaborate shorthand systems that Isaac Pitman and John Robert Gregg developed in the nineteenth century, and countless schools and publishers seized the business opportunity to train them. Talented practitioners could write at speeds up to 280 words per minute.

The texts of systems like Pitman and Gregg’s “grew increasingly complex,” then increasingly simplified during latter half of the 20th century. “In 1903, the publishers of the Gregg method released the first novel entirely rendered in shorthand—an 87-page edition of Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son by George Horace Latimer.”

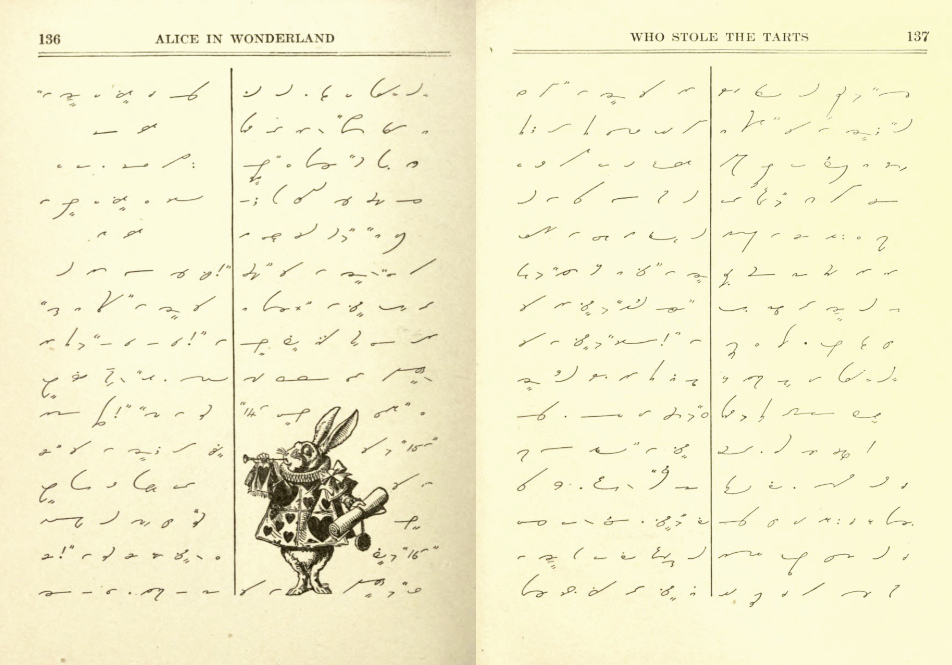

More literature in shorthand followed, marking the Gregg system’s most baroque period. Ten years later saw the publication of Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, then, in 1918, with Alice in Wonderland, Hamlet, and A Christmas Carol, and stories like Guy de Maupassant’s “The Diamond Necklace,” Edgar Allan Poe’s “A Descent into the Maelström.” All of this literary shorthand is written in what is known as “Pre-Anniversary” Gregg, which contained the largest number of symbols and devices. In 1929, a year-late “Anniversary Edition” began a period of simplification that culminated in 1988, a century after the system’s first publication.

The literature published in Gregg shorthand joined in a history of shorthand “used by (or to preserve the work of) everyone from Cicero to Luther to Shakespeare to Pepys,” writes the Public Domain Review. And yet, the “utilitarian function of shorthand sits a little oddly perhaps with literature, given the novel or the poem is a form associated with a different realm: that of leisure.” One should not have to train in a specialized phonemic orthography to read and enjoy Alice in Wonderland, but, on the off chance that you did so train, there is at least much enjoyable and edifying material with which to practice, or show off, your skills.

It would, I maintain, be a fascinating exercise to compare translations of these well-known works from the shorthand with their originals manuscripts written in the phonetic chaos of the English we recognize. Whether or not you have the skill to undertake this experiment, you can see many of these Gregg’s shorthand editions here and at the Internet Archive. Just click on the embeds above to see larger images and view and download a variety of formats.

Related Content:

Learn 48 Languages Online for Free: Spanish, Chinese, English & More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Really um very impressed to learn this, kindly linked in my mail regularly