Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel The Buried Giant begins with an immersive depiction of what it might have been like to live in a European village during the middle ages. Or what it might feel like for us moderns, at least. The couple at the center of the story spends several pages fretting over the loss of a candle, their only one. Without it, their nights are pitch black. In the day, they wander in a fog, unable to remember anything. Though the cause of this turns out to be dark magic, one can’t help thinking that a smartphone would immediately solve all their problems.

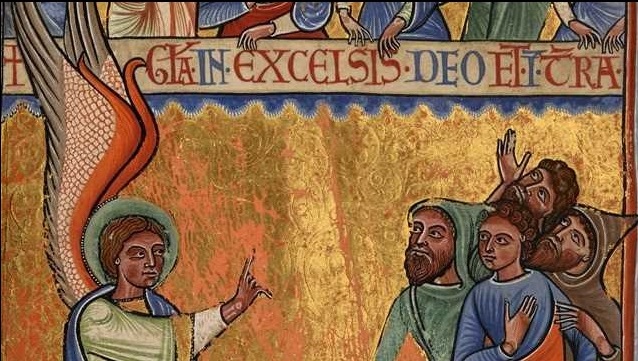

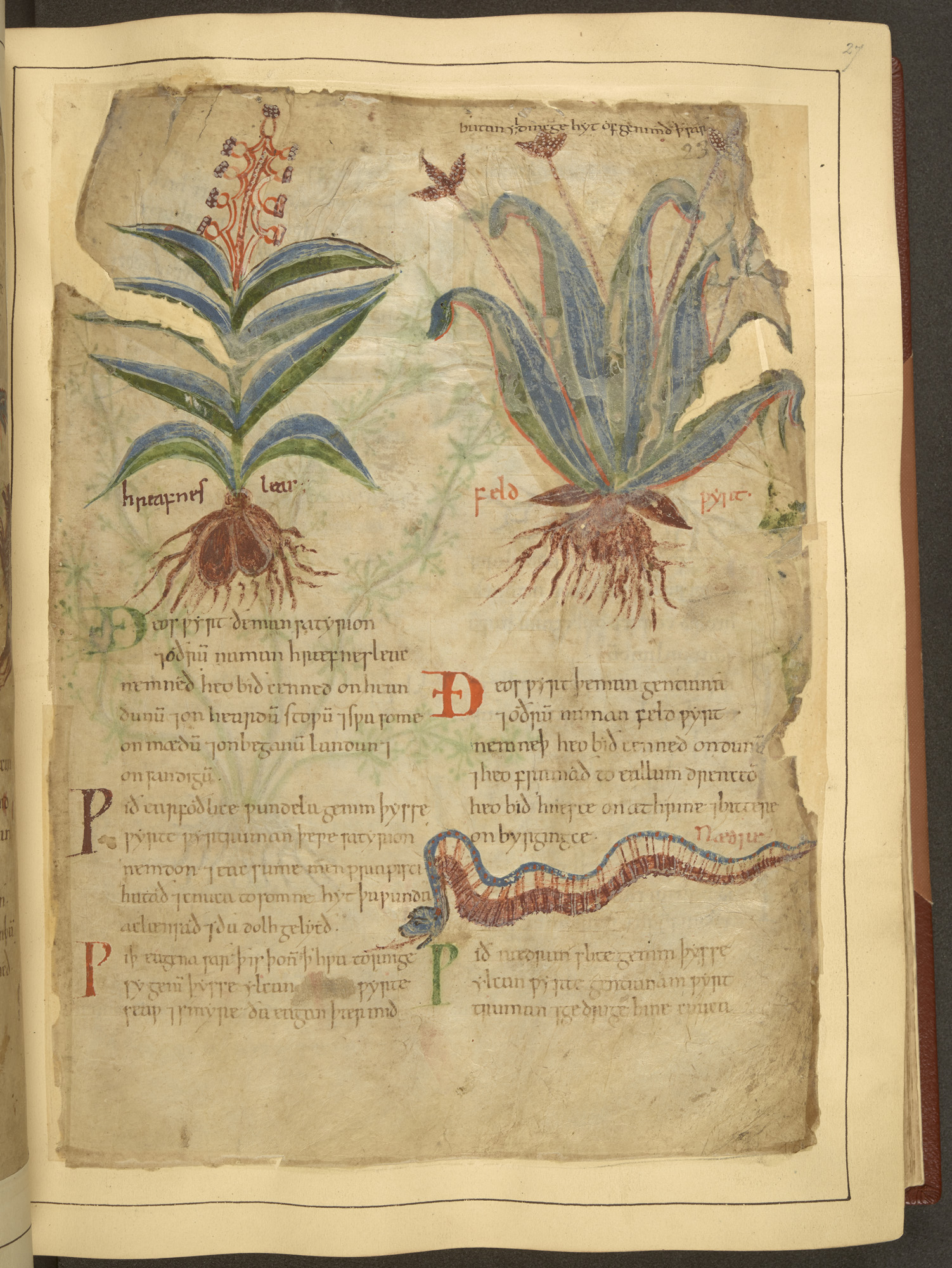

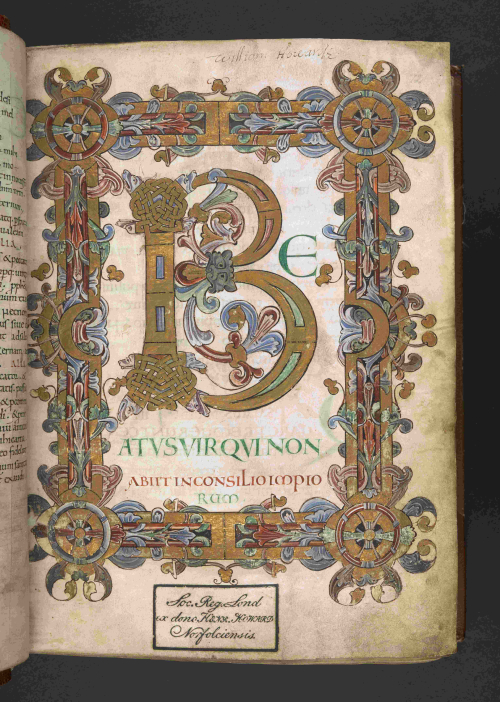

This was a time not only before mobile video, but when images of any kind were scarce, when every book was painstakingly copied by hand in careful, elegant script. Many of those rare, scribal copies were not illustrated, they were “illuminated.” Their pages shone out into the darkness and fog. Most of the population could not read them, but they could, in rare instances when they might catch a glimpse, be deeply moved by the colorful, stylized images and lettering.

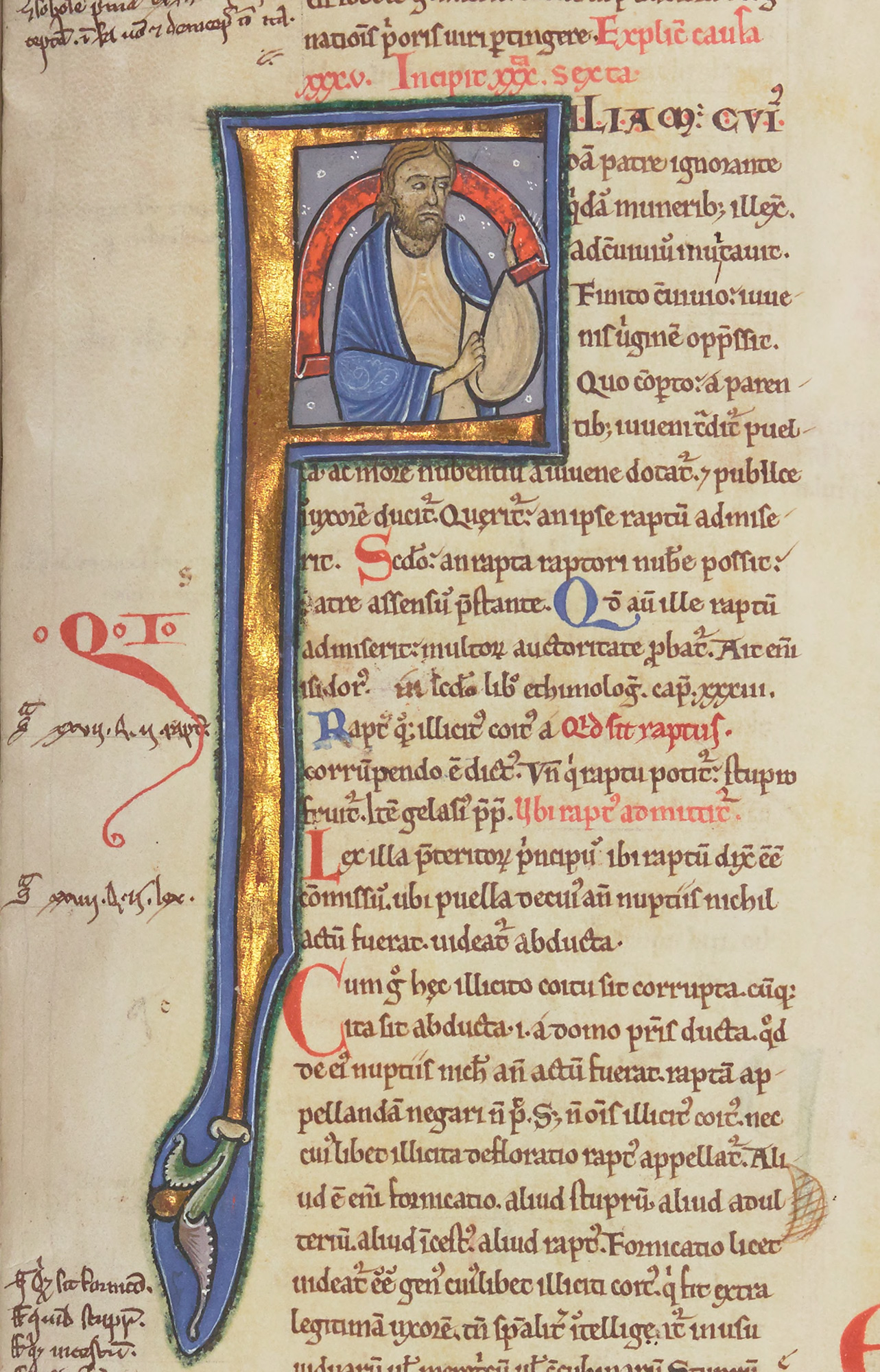

For the intellectual classes, illumination constituted a language of its own, framing and interpreting medical, classical, and legal texts, gospels and works by the church fathers. Not all books received this treatment but the “most luxurious,” notes the British Library, were “literally ‘lit up’ by decorations and pictures in brightly coloured pigments and burnished gold leaf.” For centuries, despite the explosion of image-making technologies of every kind, most of us, unless we were scholars or aristocrats, were in the same position vis-à-vis these stunning artifacts as the average medieval peasant. Medieval manuscripts were locked away in rare book rooms and seen by very few.

The situation has changed dramatically as libraries digitize their holdings. Last November, hundreds more rare, valuable medieval manuscripts became available to everyone when the British Library and the Bibliothèque nationale de France launched a joint project, making “800 manuscripts decorated before the year 1200 available freely” online, as the BL blog announced in 2016. Both institutions provided 400 manuscripts each for digitization. Some of these are currently on display at the wildly popular, sold-out British Library exhibition Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War. Now they are also virtual public property, as it were, thanks to a grant from the Polonsky Foundation.

That these fragile artifacts have been so inaccessible, kept under glass and well away from insects, thieves, and vandals, now means they are in a condition to be digitally copied and uploaded in high resolution for close viewing, comparison, and careful study. Medievalists.net describes the complementary websites the two libraries have launched:

The first, France-England: medieval manuscripts between 700 and 1200, has been created by the Bibliothèque nationale de France based on the Gallica marque blanche infrastructure, using the IIIF standard and Mirador viewer to make the images held by the different institutions interoperable and enable them to be compared side-by-side within the same digital library or annotated. The second website, Medieval England and France, 700‑1200, is aimed at a wider public audience, and has been developed by the British Library to showcase a selection of manuscripts as well as articles, essays and video clips.

The French site has ports of entry according to theme, author, place, and century, and many links to resources for scholars. The British Library site features curated selections, introduced by accessible articles. Laypeople with little experience studying medieval manuscripts can learn about legal, medical, and musical texts, see how the writings of the church fathers received special attention in monastic culture, and learn how manuscripts circulated before 1200. Those who know what they are looking for can conduct advanced searches at the Medieval Manuscripts site, and download a full list of all 800 manuscripts here.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The link to ‘France-England: medieval manuscripts between 700 and 1200’ doesn’t work (code 404)

The link is :

https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org

and not

https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/%5BL,NE,R=301%5D

To OpenCulture : would you be able to correct it ?

Many thanks,

Try this link https://manuscrits-france-angleterre.org/polonsky/fr/content/accueil-fr?mode=desktop

Fixed

A very kind and interesting initiative.

One more Fruit of 73 years of peace after the latest big clash…

Stef

Mediaevist, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 1988).

I’m interesting seriously to be one among your organization, with all strength and souls