Nothing could seem more ordinary to anyone who has grown up with a musician in the house, or taken music classes themselves, than sheaves of sheet music: quarter, half, and whole notes tripping through orderly staffs in chords, arpeggios, and melodies. But the process of making those sheets of music is probably far less familiar to most of us. Music printing history, as the site Music Printing History shows, parallels book printing, but uses the technologies differently, from woodblock to lithography to photographic reproduction to perhaps a rarely seen method—the music typewriter.

These ingenious machines do exactly what it sounds like they do, in typewriter-like forms we’ll recognize and other forms we will not. The first patent for such a device, filed in 1885 by Charles Spiro, shows an object resembling a sewing machine.

The next invention, first patented by F. Dogilbert in 1906, resembles a mechanical engraving machine—and indeed, that’s more or less what it was. By contrast, the 1946 Musicwriter, invented by Cecil S. Effinger, looks just like an early IBM typewriter with a QWERTY keyboard. The next version of the machine was, in fact, a word processor made by IBM.

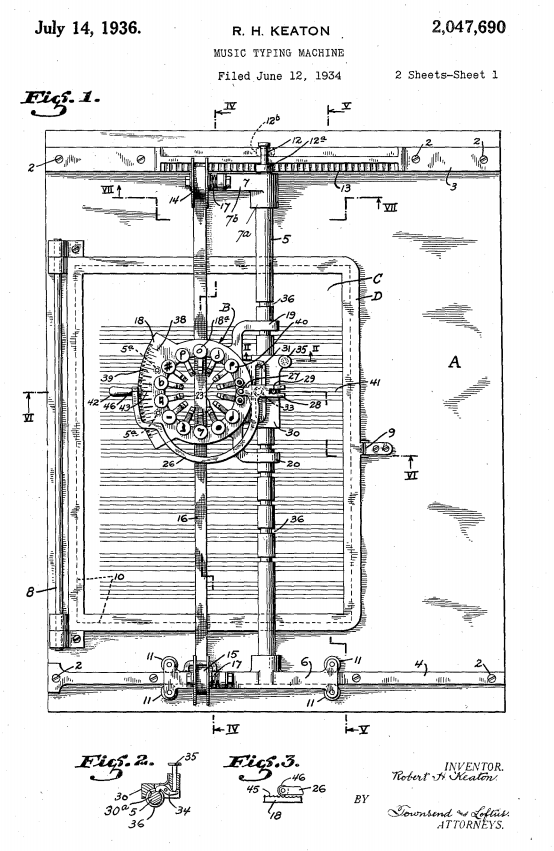

One invention Music Printing History does not mention was made by a woman, Miss Lillian Pavey, in 1961. In the British Pathé newsreel film above, you can see her typewriter in action as she transcribes music from a record in real time. In-between the earliest music typewriters, which were not mass-marketed to consumers, and IBM’s slick, 1988 Musicwriter II, which was, there is the odd Keaton Music Typewriter, first patented with 14 keys in 1936, then again in 1953 in a 33-key version.

See the Keaton’s clunky operation at the top of the post. It looks a little like a seismograph or lie detector machine with a semicircular double ring of keys (in the 33-key design) in the center of a metal carriage. (See the original patent below.) Contrary to the Pathé newsman’s claim that no one had succeeded in making a working music typewriter, the Keaton and other models to follow in the 40s and 50s sold, though not in large quantities, and “made it easier for publishers, educators, and other musicians to produce music copies in quantity.” Typed sheet music could easily be mass-reproduced by photography.

Nonetheless, Music Printing History notes, “composers… preferred to write the music out by hand.” The typewriter was mainly offered as a tool for mechanical reproduction, not spontaneous composition. Computers have changed things such that composers seem to have the same kinds of debates about handwriting verses digital as writers do. But where the typewriter is still a powerful symbol of literary art—for some an instrument as distinctive and worthy of study as the guitars of rock ‘n’ roll greats—the music typewriter is an oddity, a mechanical curiosity no one associates with creation.

Yet, as “the most vintage and wonderfully impractical thing ever,” as Classic Fm dubs the device, unwieldy machines like the Keaton remain high on the list of cool, quirky inventions its most likely customers didn’t really seem to need.

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

Behold Friedrich Nietzsche’s Curious Typewriter, the “Malling-Hansen Writing Ball”

The Enduring Analog Underworld of Gramercy Typewriter

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply